.

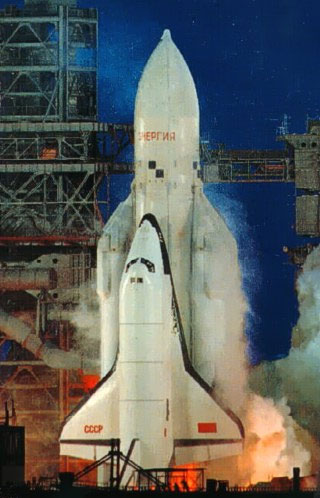

Just before dawn on the morning of November 15, 1988, the mood at Baikonur, the Soviet Union’s launch site, was tense and businesslike. It was a cold morning marked by low cloud cover, a persistent drizzle, and warnings of gale force winds. It was a terrible day for a launch.

But on the pad stood the Energiya rocket, fueled and ready to carry the Buran space shuttle orbiter on its maiden flight. A thin layer of ice coating both vehicles threatened to postpone the event, though no one on site wanted to see the spacecraft stay on the pad. A scrubbed launch could delay Buran’s debut until the spring—or even deal a death blow to the whole program. Weighing the odds, Soviet space officials decided to take their chances. At 8:00am local time, exactly on schedule, Energiya roared to life and Buran took flight.

The next morning, half a world away in the United States, American reports on the mission focused as much on Buran’s similarity to NASA’s space shuttle as on the flight itself. The Soviet design seems indebted to NASA, newspapers proclaimed, citing experts’ opinions that there were few, if any, fundamental differences between the spacecraft. This sentiment has persisted in the general public’s mind for the nearly 30 years since Buran flew.

There’s certainly truth to reports that the Soviets copied the American shuttle, but the two vehicles aren’t identical. And while imitation may be the sincerest form of flattery, this wasn’t what the Soviets had in mind when they decided to build a space shuttle of their own.

The end of Apollo and the advent of the Space Shuttle

After successfully landing humans on the Moon in 1969, NASA began planning its next major program. There were a handful of options, including continued lunar exploration or the construction of an Earth orbital space station and reusable spacecraft combination. But NASA’s budget was shrinking rapidly, and after weighing the finances of the options, President Nixon made a decision. On January 5, 1972, he issued a statement saying that NASA would turn its attention to building an “entirely new type of space transportation system designed to help transform the space frontier… a space vehicle that can shuttle astronauts repeatedly from Earth to orbit and back.” NASA would build a space shuttle, even though it lacked a space station to service.

As the program took shape, NASA presented the shuttle as the vehicle that would make spaceflight routine without breaking the budget. It would also make spaceflight cost-effective, in part because the US Department of Defense would be sharing the cost. That deal meant that the DOD set the dimensions of the shuttle’s payload bay so it could carry military satellites into orbit.

The American announcement of the shuttle program didn’t immediately sound alarm bells in the Soviet Union. Having lost the race to the Moon, the nation wasn’t looking to begin another competitive program. Instead, the Soviets were focusing on the loftier goal of building a manned base on the Moon, a useful scientific endeavor that would also surpass the Americans’ six brief visits with Apollo missions. Between this lunar program, the ongoing Soyuz and Salyut programs, and the existing launch vehicle programs, there wasn’t a design bureau in the Soviet Union with enough time to work on developing a reusable shuttle. More to the point, there was simply no obvious need for such a spacecraft in the Soviets’ space program.

But plans for a lunar base hit a wall in 1974. Vasiliy Mishin, head of the TsKBEM design bureau that was once led by Sergei Korolev, was sacked and replaced by Korolev’s old rival Valentin Glushko. Glushko merged TsKBEM with his own KB Energomash organization to form a new bureau called NPO Energiya. And his first move in his new position was to halt all work on the lunar project and its associated N-1 launch vehicle so that he could consider other possible directions. He established a working group to study various reusable spacecraft, and as the lunar base fell out of favor, the idea of a shuttle moved to the foreground.

Glushko’s shuttle got a boost a year later. By 1975, the Soviet military had three years to brood over what the Americans might be up to with a reusable spacecraft as large as the one they were building. NASA even made details about its shuttle program public, so there was little guesswork needed on the Soviets’ part. Soviet military studies found that the American shuttle wouldn’t be economically viable given the parameters NASA announced, and its payload capacity seemed too high for a civilian program.

Launching up to 60 times per year with the capacity to lift nearly 25,000 kg into low-Earth orbit meant that the United States could put a lot of hardware into space each year. It seemed plausible that the Americans were planning to launch experimental laser weapons into orbit—and with the shuttle’s capacity to bring 15 tons back from space, these weapons could be tested in orbit and then be brought back for modification. In the long term, this capability would let the Americans build a functioning orbital battle station.

Soviet fears seemed to be confirmed with the announcement that a shuttle launch facility would be built at the Vandenberg Air Force Base to facilitate DOD launches. And when NASA announced the shuttle’s 1,242-mile cross-range capability, the spacecraft itself started to look like a weapon that might be able to dip into the atmosphere and drop bombs. The Soviets could only conclude that the American shuttle was a military program, and responding in kind became a national priority.

The Soviet space shuttle decision

Faced with the poorly understood threat of a military space shuttle, the Soviets decided that copying the American spacecraft exactly was the best bet. The logic was simple: if the Americans were planning something that needed a vehicle that big, the Soviets ought to build one as well and be ready to match their adversary even if they didn’t know exactly what they were matching.

After a series of meetings between officials of the Ministry of General Machine Building, the Ministry of Defense, and the NPO Energiya organization, the Soviet shuttle program began on February 17, 1976. That’s when an official decree titled “On the Development of a Reusable Space System and Future Space Complexes” was issued by the Central Committee of the Soviet Communist Party and the Council of Ministers of the USSR. It described the new vehicle as one that would counteract military measures taken by “the likely adversary” in space; contribute to national defense, economy, and science goals; support the expansion of the military into space; and put objects into orbit and return them for servicing.

Meeting these goals would give the shuttle three mission profiles: short missions three days or less to place heavy payloads into orbit; medium duration missions lasting up to eight days during which crews could deploy and service satellites; and long duration missions, lasting up to 30 days, that would be devoted to science goals.

Superficially, the Soviet shuttle, formally called the Reusable Space System, had the same goals as the American version. But there was one crucial difference between the two programs: the Americans planned for the shuttle to take the place of all existing launch vehicles, while the Soviets’ shuttle would add to their roster of rockets. Work would continue on both the Soyuz and Salyut programs as well as the Mir space station.

Two shuttles: Different, but the same

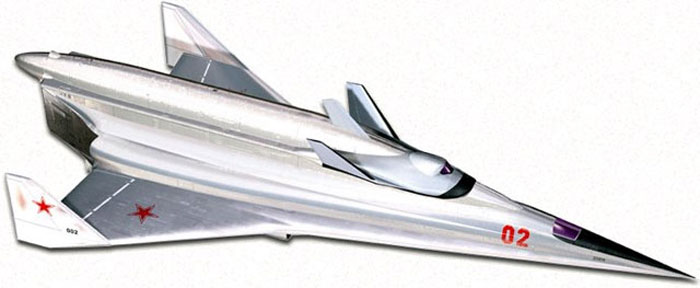

Though the 1976 decree approved the Soviet space shuttle program, it didn’t specify what form the spacecraft should take. A number of possible arrangements emerged, some with the orbiter mounted on top of a launch vehicle and others with it strapped to the side. Studies favored the latter configuration, and the basic design was frozen within months. The winged orbiter would ride into orbit strapped to a launch vehicle composed of a core stage with four RD-0120 cryogenic engines and four strap-on boosters, each powered by RD-123 LOX/kerosene engines.

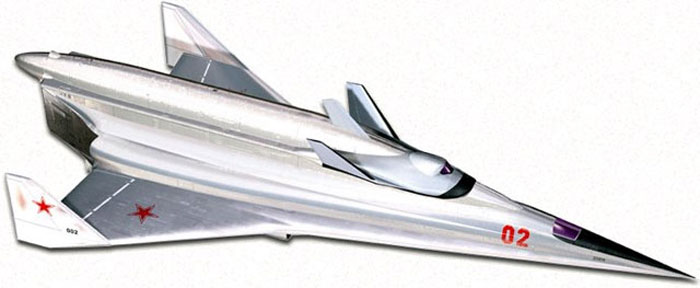

Settling on the shape of the orbiter took a little longer. Some argued for a spacecraft reminiscent of the short-lived Spiral spaceplane, while others argued in favor of copying the American design outright. The final decision struck a balance. Built to nearly the same dimensions as the American spacecraft, the Soviet shuttle had a forward crew cabin, a central payload bay equipped with two maneuvering arms, and a rear propulsion unit.

.

The crew module was shaped like a truncated cone at 17.7 feet long and high and a little over 16 feet wide. Pressurized with a mixture of nitrogen and oxygen, it could hold a crew of 10 cosmonauts spread among the upper, mid, and lower decks. It housed six workstations: RM-1 and RM-2, together called Vega 1, were manned by the commander and co-pilot respectively during launch and landing; to the right was RM-3, the flight engineer’s workstation; RM-4, located underneath a porthole window, was the navigator’s station from which he could monitor orbital operations like rendezvous and docking; RM-5 was dedicated to operating the payload bay doors and operating the two arms; and RM-6 controlled the cargo and payload bays.

Across the six workstations, the Soviet shuttle had fewer displays than its American counterparts owing to its higher level of automation. This orbiter’s sophisticated avionics system controlled all vital functions. It could turn systems on and off and monitor onboard operations while constantly checking for anomalies. Its guidance, navigation, and control system relied on three gyro-stabilized platforms and used a vertical radio altimeter as a backup. At the heart of the orbiter were two redundant Soviet-built computers known as the Central Computing System and the Peripheral Computing System, each consisting of four identical computers called Biser-4.

Though different internally, the Soviet and American shuttles looked nearly identical externally because of the Soviets’ use of NASA’s shuttle thermal protection studies. Both vehicles used the same silica tiles and reinforced carbon-carbon protecting the nose cap and leading edges on the wings. But the two shuttles' looks differed from the back; the Soviet shuttle didn’t include a main engine. Its rear section housed the Combined Engine Installation, which comprised an integrated set of orbital maneuvering engines, thrusters, and the necessary plumbing to pump a combination of liquid oxygen and a synthetic hydrocarbon known as sintin through the system. The vehicle also had a propulsive abort system: four small solid-fuel motors could instantly separate the orbiter from the launch vehicle’s core stage in the event of a sudden catastrophic failure.

The American-inspired Soviet shuttle design was frozen in June of 1979.

Spy game

Anticipating that the Soviets would respond to NASA’s announcement of the shuttle program with a reusable shuttle of their own, the CIA started looking for indications of a new Soviet space program in the mid-1970s. None were forthcoming, in equal parts because the Soviet decision to build a shuttle came years after America’s and because of the Soviets' traditionally secretive nature. But it’s impossible to hide a space shuttle forever, and clues eventually surfaced. There were reports of winged vehicles flying aboard Proton rockets (these turned out to be erroneous) and half-constructed runways found in aerial reconnaissance photographs of Baikonur.

.

Russian trawler trying to obscure the BOR-4 spaceplane with orange smoke during recovery operation.

.

The first undeniable evidence of a new Soviet spacecraft came in April of 1983. The Australian Air Force snapped and released pictures of the Soviet Navy recovering a small-scale spaceplane from the Indian Ocean. With no additional information, some American analysts assumed this was a model of the supposed shuttle. Others disagreed, suspecting that it was a test article meant to test materials to be used for reentry protection. This latter guess turned out to be correct. Called BOR-4, the vehicle was a repurposed scale model of the short-lived Spiral spaceplane program, modified to test the shuttle’s thermal protection system.

The CIA published its speculation on the Soviet shuttle in the 1983 edition of “Soviet Military Power.” The document envisioned a system similar to—but more powerful than—the American Shuttle. The CIA expected the Soviet vehicle could lift 60 tons into orbit with a single launch.

Months later, photoreconnaissance revealed a test orbiter on top of a carrier aircraft and an Energia rocket on the launch pad. The appearance of flight hardware helped American intelligence refine its estimates of the Soviet shuttle’s power, but the CIA didn't get it right until 1986. A drawing in that year’s edition of “Soviet Military Power” showed an orbiter, remarkably like the American shuttle, strapped to a massive core rocket stage flanked by four booster rockets.

Buran takes flight

Less than a year later, at a press conference on April 8, 1987, Glavkosmos, the international relations arm of the Soviet Ministry of General Machine Building, publicly acknowledged that the Soviet Union was building a space shuttle. And it was at this point that the spacecraft got a name. When the first flight-worthy Soviet shuttle arrived at Baikonur on December 11, 1985 riding piggy back on a VM-T carrier aircraft, it had Baykal painted on the side. In April of 1986, it was renamed Buran, which roughly translates to “snowstorm on the steppes.”

Buran’s first flight, it was announced, would be a two-orbit shakedown cruise, flown without anyone on board. The plan simplified matters. There were no fuel cells needed to power the shuttle, and the environment didn’t have to support crew. But there was a tradeoff in the man-hours spent developing the autopilot program; the version that flew was the programmers’ 21st version. And though the flight was unmanned, the mission did have a payload. Inside the cargo bay would be a pressurized module called the Unit for Additional Instruments that could record 6,000 parameters of the flight and carry extra equipment like spare batteries.

In a first for the Soviet Union, the space program promised to broadcast the launch live on television. However, it was a promise it wouldn’t keep.

After months of official reports saying Buran’s launch was imminent, the first attempt came on October 29, 1988. It was a perfect day with clear skies and no wind, and in spite of frequent holds, the countdown progressed. Then, at T–51 seconds, a platform outside the intertank area of the core stage took so long to retract that the rocket’s computer stopped the countdown. The launch was scrubbed and eventually rescheduled for November 15.

Apart from terrible weather, the countdown on the second launch attempt was much smoother. The Energiya rocket lifted off through stormy skies exactly on schedule at 8:00am local time at Baikonur. The four expended external boosters separated from the core stage and fell away. Seven minutes and 48 seconds after launch, Energiya’s work was done and its engines throttled down. At eight minutes and 2.8 seconds after launch, the orbiter separated from the core stage at an altitude of about 93 miles. Buran positioned itself for the all-important burn of its two orbital maneuvering units that fired to put it into the correct orbit. Thirty-nine minutes later, Buran was in its final, nearly circular 158 by 153 mile orbit.

An hour and a half after launch, Buran’s software began its reentry and landing sequence. Propellant was transferred forward from rear tanks to meet center of gravity requirements, and the orbiter maneuvered itself so that it was leading with its tail, orienting its engines for the deorbit burn. The burn was nominal, and half an hour later with its nose pitched high, Buran entered the atmosphere off the western coast of Africa.

To get around the winds still blowing at Baikonur, the orbiter was programmed to approach the runway from the east. But the onboard computer was tasked with making its own decisions in the final landing phases, taking into account realtime data. It was tense for those watching the telemetry. When Buran changed its approach profile at the last minute to dissipate more energy, technicians worried that a flaw in the programming was about to result in a crash landing.

Battling headwinds and crosswinds, the orbiter touched down just one second earlier than planned, traveling at 163 miles per hour. The drogue chutes deployed, slowing Buran until it rolled to a stop at 10:25.24 local time. The end of the mission was publicly marked by a brief and businesslike announcement from TASS.

.

A Buran test model on display at the Baikonur Museum in Kazakhstan.

.

Aftermath: Death of a dream

Within hours of the shuttle’s landing, the Central Committee of the Communist Party sent a congratulatory message to the Buran-Energiya team. The mission’s success, the note read, marked the opening of a new stage in the Soviet space research program and promised to extend the nation’s opportunities for future exploration. It also definitively demonstrated the country’s high level of scientific and technological potential. The press similarly hailed the flight as a portent of change in the Soviet space program, though Western news tempered its praise with questions about Buran’s similarity to NASA’s space shuttle.

Western suspicions weren’t the only negative responses to the flight. There were dissenters, some within the Soviet space and science communities, who called Buran a costly mistake. Critics pointed out that no Soviet satellites were so valuable that they would need to be brought back from orbit for repairs. The lengthy launch preparations, limited launch azimuths, and slow response time as a weapons system left few uses for Buran that couldn’t be handled by existing expendable boosters and spacecraft, all of which were cheaper. Consensus among critics was that the program would languish without a concerted effort to make it truly cost effective.

The future of the Energiya-Buran program was on the agenda of the Defense Council’s May 6, 1989, meeting, which was chaired by Mikhail Gorbachov, then-general secretary of the Communist Party. The council expressed dissatisfaction with the plan Buran representatives laid out for the shuttle: construction of five orbiters that would begin carrying manned missions to the Mir 2 space station in 1992. It demanded the program be pared down and that the group fast-track a program to develop missions focused on Buran. Nevertheless, it approved the program to run through 2000.

But politics wouldn’t favor Buran. When the USSR dissolved in 1991, so too did the Ministry of General Machine Building, which had seen the shuttle grow from idea to flight article. All rocket and space enterprises were transferred to the Russian Ministry of the Industry. After a number of design bureaus, NPO Energiya included, refused to cooperate with this new structure, Gorbachev’s successor, Boris Yeltsin, founded a national space agency. The new Russian Space Agency’s plans didn’t include Buran-Energiya. The system seemed to have no place in the new political and economic climate.

In May of 1993, a statement from the Council of Chief Designers said that in spite of Energiya-Buran’s success, the government was in no position to ensure continued work on the program. It was as close to a formal cancellation as the Soviet shuttle ever got. By then, the Mir 2 space station that Buran was supposed to build and service merged with the United States’ Freedom space station to become the International Space Station.

Buran’s cancellation was inevitable. In 1991, then-leader of NPO Energiya Yuriy Semyonov admitted in a TV interview that Buran was developed by the Soviet Defense Military to counter the American shuttle program. In that goal—matching a potential threat from the adversary—the program was a striking success. And really, science goals beyond this political one could have only ever been secondary.

When the program was cancelled, half-built orbiters were suddenly homeless and unwanted. Orbiter OK-1.02, a copy of the original Buran known as Ptichka (little bird) or Buria (storm), was almost finished when the Buran program ended in 1993; all that remained was to install a handful of electronic units. It’s in a hangar at Baikonur, but the orbiter is actually the property of Kazakhstan. Orbiter OK-2.01, the first in a second series of orbiters that included a number of improvements over the original model, was also under construction when the program was canceled. It was dismantled and sat gathering dust at the Tushina factory near Moscow for years until 2011 when it was reportedly moved to an aviation museum in Germany for restoration. Orbiter OK-2.02, in the early phases of construction when the program ended, was quickly dismantled; the few pieces that were salvaged were sold online. Construction had just begun on a fifth orbiter, OK-2.03, in 1993. It was dismantled and its remains were destroyed.

As for Buran, the only Soviet shuttle to fly, there’s nothing left. In 1999, the orbiter was moved into the MIK building at the Baikonur Space Port, where it was displayed horizontally mounted on top of an Energiya rocket. But the building fell under disrepair, and in 2002 the hangar’s roof collapsed. Seven workers were killed and both Energiya and Buran were destroyed.

Western suspicions weren’t the only negative responses to the flight. There were dissenters, some within the Soviet space and science communities, who called Buran a costly mistake. Critics pointed out that no Soviet satellites were so valuable that they would need to be brought back from orbit for repairs. The lengthy launch preparations, limited launch azimuths, and slow response time as a weapons system left few uses for Buran that couldn’t be handled by existing expendable boosters and spacecraft, all of which were cheaper. Consensus among critics was that the program would languish without a concerted effort to make it truly cost effective.

The future of the Energiya-Buran program was on the agenda of the Defense Council’s May 6, 1989, meeting, which was chaired by Mikhail Gorbachov, then-general secretary of the Communist Party. The council expressed dissatisfaction with the plan Buran representatives laid out for the shuttle: construction of five orbiters that would begin carrying manned missions to the Mir 2 space station in 1992. It demanded the program be pared down and that the group fast-track a program to develop missions focused on Buran. Nevertheless, it approved the program to run through 2000.

But politics wouldn’t favor Buran. When the USSR dissolved in 1991, so too did the Ministry of General Machine Building, which had seen the shuttle grow from idea to flight article. All rocket and space enterprises were transferred to the Russian Ministry of the Industry. After a number of design bureaus, NPO Energiya included, refused to cooperate with this new structure, Gorbachev’s successor, Boris Yeltsin, founded a national space agency. The new Russian Space Agency’s plans didn’t include Buran-Energiya. The system seemed to have no place in the new political and economic climate.

In May of 1993, a statement from the Council of Chief Designers said that in spite of Energiya-Buran’s success, the government was in no position to ensure continued work on the program. It was as close to a formal cancellation as the Soviet shuttle ever got. By then, the Mir 2 space station that Buran was supposed to build and service merged with the United States’ Freedom space station to become the International Space Station.

Buran’s cancellation was inevitable. In 1991, then-leader of NPO Energiya Yuriy Semyonov admitted in a TV interview that Buran was developed by the Soviet Defense Military to counter the American shuttle program. In that goal—matching a potential threat from the adversary—the program was a striking success. And really, science goals beyond this political one could have only ever been secondary.

When the program was cancelled, half-built orbiters were suddenly homeless and unwanted. Orbiter OK-1.02, a copy of the original Buran known as Ptichka (little bird) or Buria (storm), was almost finished when the Buran program ended in 1993; all that remained was to install a handful of electronic units. It’s in a hangar at Baikonur, but the orbiter is actually the property of Kazakhstan. Orbiter OK-2.01, the first in a second series of orbiters that included a number of improvements over the original model, was also under construction when the program was canceled. It was dismantled and sat gathering dust at the Tushina factory near Moscow for years until 2011 when it was reportedly moved to an aviation museum in Germany for restoration. Orbiter OK-2.02, in the early phases of construction when the program ended, was quickly dismantled; the few pieces that were salvaged were sold online. Construction had just begun on a fifth orbiter, OK-2.03, in 1993. It was dismantled and its remains were destroyed.

As for Buran, the only Soviet shuttle to fly, there’s nothing left. In 1999, the orbiter was moved into the MIK building at the Baikonur Space Port, where it was displayed horizontally mounted on top of an Energiya rocket. But the building fell under disrepair, and in 2002 the hangar’s roof collapsed. Seven workers were killed and both Energiya and Buran were destroyed.

Quelle: ars technica

.

Ein weiteres Buran-Shuttle findet man im Technik-Museum in Speyer/Deutschland, welches auf abenteuerliche Art aus aus der Wüste nach Deutschland kam. Nachfolgende Fotos wurden im Jahre 2010 in Speyer gemacht. Fotos: ©-hjkc

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Desweiteren gibt es in Speyer den UdSSR-Test-Shuttle BOR-5

.

.

.

Mehr Fotos von Buran gibt es unter der Technik-Galerie Raumfahrt.

7087 Views