1.01.2022

James Webb Space Telescope uncovers massive sunshield in next step of risky deployment

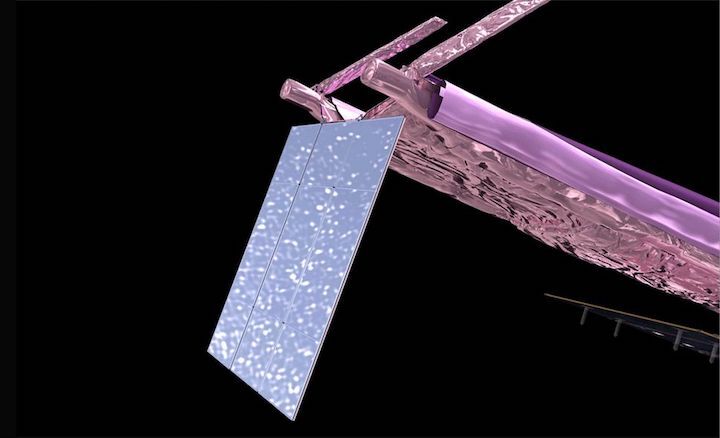

The aft momentum flap of the James Webb Space Telescope (bottom left) is seen in its deployed configuration in this NASA graphic. (Image credit: NASA

The James Webb Space Telescope has unwrapped its sunshield, crossing another important item off of its lengthy and risky deployment to-do list.

After successfully extending its deployable tower assembly (DTA), a structure that connects Webb's two halves, on Thursday (Dec. 29), the telescope had the room to begin the preliminary steps to unfurl its gigantic sunshield. Today (Dec. 30), mission teams completed two major next steps: deploying the James Webb Space Telescope's aft momentum flap and releasing the sunshield's protective membrane cover.

Webb still must unfurl the sunshield, which it will do in the next day or so by extending two booms. The mission team will then spend a few days getting the five-layer structure to the proper tension, wrapping up such work no earlier than Sunday (Jan. 2).

That will end the sunshield deployment, and the Webb team will move on to the telescope's optics. Webb's primary and secondary mirrors are expected to be deployed by Jan. 7, according to NASA, bringing the observatory's deployment phase to and end.

Webb's sunshield is a vital component that keeps the space telescope's optics and instruments at the correct (super cold) temperature. But the sunshield, which extends to about 70 by 47 feet (21 by 14 meters), is so large that to get it to space the mission team had to fold it up. That means that now that Webb is in space, it has to unfold.

"Just as a ship's mast must be set in position and the rigging established before the ship unfurls its sails, Webb's pallet structures, momentum flap and mid-booms will soon all be in place for Webb's silver sunshield to unfold," NASA saidin a statement Thursday referencing Webb's previous step of deploying its pallet structures and its upcoming plan to deploy mid-booms.

Today, soon after 9 a.m. EDT (1400 GMT), the Webb team deployed the "aft momentum flap" in a maneuver that took about eight minutes, according to the above statement from NASA. This flap helps Webb maintain its orientation in orbit without using extra fuel.

Once the sunshield is deployed, it will be pushed continuously by photons from the sun. The momentum flap will help counteract this potential sunlight nudge, allowing the observatory to conserve fuel it would have otherwise needed to use to maintain its position.

After deploying the flap, the Webb team released the protective membrane cover that enveloped and protected the sunshield during ground activities and Webb's launch to space. The cover was released via electrically activated devices, according to NASA.

Deploying Webb and its massive sunshield is a tremendous and risky undertaking. Webb has approximately 344 steps labeled "single point failures" and, as mission experts have said, about 80% of those take place during deployment.

NASA Administrator Bill Nelson even shared with Space.com that, while he was feeling "optimistic and confident" ahead of Webb's launch, he was also feeling "nervous," in part because of this challenging deployment process.

It will take Webb approximately 30 days from its launch date of Dec. 25 to reach its final destination, L2, or the Earth-sun Lagrange point 2, a gravitationally stable point in space about a million miles (1.5 million kilometers) from Earth.

Quelle: SC

+++

Inside the James Webb Space Telescope's control room

Webb telescope launch again pushed back

Washington (AFP) Dec 21, 2021 - The launch of the James Webb Space Telescope, which astronomers hope will herald a new era of discovery, was again pushed back Tuesday until at least Christmas Day due to "adverse weather conditions" at the launch site in French Guiana, NASA said.

The new target date, if determined to be viable, would be an actual Christmas gift for scientists who have been waiting three decades to see the largest and most powerful telescope take off for space aboard an Ariane 5 rocket.

The launch window on Saturday is from 1220-1252 GMT, the US space agency said.

"Tomorrow evening, another weather forecast will be issued in order to confirm the date of December 25," it said in a statement.

"The Ariane 5 launch vehicle and Webb are in stable and safe conditions in the Final Assembly Building."

It was the third time that the Webb telescope launch has been delayed, each time due to minor issues. The first was due to an accident during preparations for the launch in late November, and the second was due to a communications problem.

"Thank you to the teams... working overtime to ensure Webb's safe launch! The countdown to Dec. 25 is on," NASA Administrator Bill Nelson tweeted.

The Webb telescope follows in the footsteps of the legendary Hubble, but will orbit the Sun, rather than the Earth. It is hoped that the device will help answer fundamental questions about the Universe, peering back in time 13 billion years.

It will also give new information about nearly 5,000 exoplanets.

Shortly before the announcement of the delay, Nelson told a pre-launch briefing that Webb, which is named for a former NASA director, would be undertaking an "extraordinary mission."

"It's a shining example of what we can accomplish when we dream big," he said. "Webb will transform our view of the Universe."

Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator for NASA's Science Mission Directorate, said the launch would mark "the beginning of a new exciting decade of science, for NASA and for all of the international community."

The Webb telescope's orbit around the Sun will be 1.5 million kilometers (930,000 miles) from the Earth, much farther away than Hubble, which has been 600 kilometers above the Earth since 1990.

"White-knuckle" -- That's how Rusty Whitman describes the month ahead, after the launch of the historic James Webb Space Telescope, now tentatively set for Saturday.

From a secure control room in Baltimore, Maryland, Whitman and his colleagues will hold their breath as Webb comes online. But that's just the beginning.

For the first six months after Webb's launch, Whitman and the team at the Space Telescope Science Institute will monitor the observatory around the clock, making tiny adjustments to ensure it is perfectly calibrated for astronomers across the world to explore the universe.

The most crucial moments will come at the beginning of the mission: the telescope must be placed on a precise trajectory, while at the same time unfurling its massive mirror and even larger sun-shade -- a perilous choreography.

"At the end of 30 days, I will be able to breathe a sigh of relief if we're on schedule," said Whitman, flight operations system engineering manager.

He leads the team of technicians who set up Webb's control room -- a high-tech hub with dozens of screens to monitor and control the spacecraft.

In the first row, one person alone will have the power to send commands to the $10 billion machine, which will eventually settle into an orbit over a million miles (1.5 million kilometers) away.

In other stations, engineers will monitor specific systems for any anomalies.

After launch, Webb's operations are largely automated, but the team in Baltimore must be ready to handle any unexpected issues.

Luckily, they have had lots of practice.

Over the course of a dozen simulations, the engineers practiced quickly diagnosing and correcting malfunctions thought up by the team, as well as experts flown in from Europe and California.

During one of those tests, the power in the building cut out.

"It was totally unexpected," said Whitman. "The people who didn't know -- they thought it was part of the plan."

Fortunately, the team had already prepared for such an event: a back-up generator quickly restored power to the control room.

Even with the practice, Whitman is still worried about what could go wrong: "I'm nervous about the possibility that we forgot something. I'm always trying to think 'what did we forget?"

- Picking the projects -

In addition to its job of keeping Webb up and running, the Space Telescope Science Institute -- based out of the prestigious Johns Hopkins University -- manages who gets to use the pricey science tool.

While the telescope will operate practically 24/7, that only leaves 8,760 hours a year to divvy up among the scientists clamoring for their shot at a ground-breaking discovery.

Black holes, exoplanets, star clusters -- how to decide which exciting experiment gets priority?

By the end of 2020, researchers from around the world submitted over 1,200 proposals, of which 400 were eventually chosen for the first year of operation.

Hundreds of independent specialists met over two weeks in early 2021 -- online due to the pandemic -- to debate the proposals and pare down the list.

The proposals were anonymized, a practice the Space Telescope Science Institute first put in place for another project it manages, the Hubble Telescope. As a result, many more projects by women and early-career scientists were chosen.

"These are exactly the kind of people we want to use the observatory, because these are new ideas," explained Klaus Pontoppidan, the science lead for Webb.

The time each project requires for observations varies in length, some needing only a few hours and the longest needing about 200.

What will be the first images revealed to the public? "I can't say," said Pontoppidan, "that is meant to be a surprise."

The early release of images and data will quickly allow scientists to understand the telescope's capacities and set up systems that work in lock step.

"We want them to be able to do their science with it quickly," Pontoppidan explained. "Then they can come back and say 'hey - we need to do more observations based on the data we already have.'"

Pontoppidan, himself an astronomer, believes Webb will lead to many discoveries "far beyond what we've seen before."

"I'm most excited about the things that we are not predicting right now."

Before the Hubble launched, no exoplanets -- planets that orbit stars outside our solar system -- had been discovered. Scientists have since found thousands.

What will the James Webb Space Telescope reveal?

Five things to know about the James Webb Space Telescope

Washington (AFP) Dec 22, 2021 - The James Webb Space Telescope, the most powerful space observatory ever built, is now tentatively set for launch on Christmas Day, after decades of waiting.

An engineering marvel, it will help answer fundamental questions about the Universe, peering back in time 13 billion years. Here are five things to know.

- Giant gold mirror -

The telescope's centerpiece is its enormous primary mirror, a concave structure 21.5 feet (6.5 meters) wide and made up of 18 smaller hexagonal mirrors. They're made from beryllium coated with gold, optimized for reflecting infrared light from the far reaches of the universe.

The observatory also has four scientific instruments, which together fulfill two main purposes: imaging cosmic objects, and spectroscopy -- breaking down light into separate wavelengths to study the physical and chemical properties of cosmic matter.

The mirror and instruments are protected by a five-layer sunshield, which is shaped like a kite and built to unfurl to the size of a tennis court.

Its membranes are composed of kapton, a material known for its high heat resistance and stability under a wide temperature range -- both vital, since the Sun-facing side of the shield will get as hot as 230 degrees Fahrenheit (110 degrees Celsius), while the other side will reach lows of -394F.

The telescope also has a "spacecraft bus" containing its subsystems for electrical power, propulsion, communications, orientation, heating and data handling; all told, Webb weighs around as much as a school bus.

- Million-mile journey -

The telescope will be placed in orbit about a million miles from Earth, roughly four times the distance of our planet from the Moon.

Unlike Hubble, the current premier space telescope that revolves around the planet, Webb will orbit the Sun.

It will remain directly behind Earth, from the point of view of the Sun, allowing it to remain on our planet's night side. Webb's sunshield will always be between the mirror and our star.

It will take about a month to reach this region in space, known as the second Lagrange point, or L2. While astronauts have been sent to repair Hubble, no humans have ever traveled as far as Webb's planned orbit.

- High-tech origami -

Because the telescope is too large to fit into a rocket's nose cone in its operational configuration, it has to be transported folded, origami style. Unfurling is a complex and challenging task, the most daunting deployment NASA has ever attempted.

About 30 minutes after take-off, the communications antenna and solar panels supplying it with energy will be deployed.

Then comes the unfurling of the sunshield, hitherto folded like an accordion, beginning on the sixth day, well after having passed the Moon. Its thin membranes will be guided by a complex mechanism involving 400 pulleys and 1,312 feet of cable.

During the second week will finally come the mirror's turn to open. Once in its final configuration, the instruments will need to cool and be calibrated, and the mirrors very precisely adjusted.

After six months the telescope will be ready to go.

- Life, the universe, and everything -

Webb has two primary scientific missions, which together will account for more than 50 percent of its observation time. First, explore the early phases of cosmic history, looking back in time to only a few hundred million years after the Big Bang.

Astronomers want to see how the very first stars and galaxies formed, and how they evolve over time.

Its second major goal is the discovery of exoplanets, meaning planets outside the solar system. It will also investigate the potential for life on those worlds by studying their atmospheres.

The great promise of Webb lies in its infrared capacity.

Unlike the ultraviolet and visible light Hubble mostly operates in, the longer wavelengths of infrared penetrate dust more easily, allowing the early universe shrouded in clouds to come more clearly into view.

Infrared also lets scientists go further back in time because of a phenomenon called redshifting. Light from objects farther away is stretched as the universe expands, towards the infrared end of the spectrum.

Also planned are closer observations, in our solar system, of Mars and of Europa, Jupiter's icy moon.

- Decades in the making -

Astronomers began debating the telescope that should succeed Hubble in the 1990s, with Webb's construction beginning in 2004.

Launch has been pushed back several times, initially penciled for 2007, then 2018...mainly because of the complexities associated with development.

The observatory is the result of an immense international collaboration, and integrates Canadian and European instruments.

More than 10,000 people worked on the project, with the budget eventually snowballing to around $10 billion.

The mission is set to last for at least five years, but hopefully 10 or more.

Quelle: SD