4.09.2020

University of Maryland physicists help identify merging black holes that may redefine size limits for collapsed stars

Scientists observed what appears to be a bulked-up black hole tangling with a more ordinary one. The research team, which includes physicists from the University of Maryland, detected two black holes merging, but one of the black holes was 1 1/2 times more massive than any ever observed in a black hole collision. The researchers believe the heavier black hole in the pair may be the result of a previous merger between two black holes.

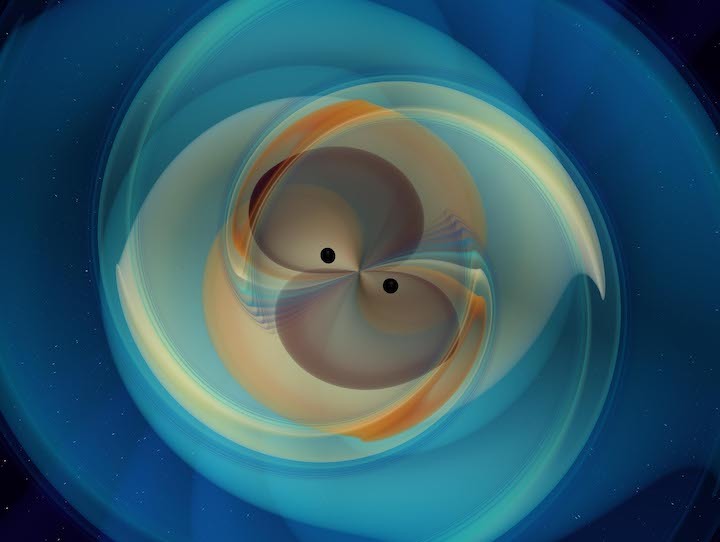

Numerical simulation of two black holes that spiral inwards and merge, emitting gravitational waves. The simulated gravitational wave signal is consistent with the observation made by the LIGO and Virgo gravitational wave detectors on May 21st, 2019 (GW190521). Image Copyright © N. Fischer, H. Pfeiffer, A. Buonanno (Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics), Simulating eXtreme Spacetimes (SXS) Collaboration.

This type of hierarchical combining of black holes has been hypothesized in the past but the observed event, labeled GW190521, would be the first evidence for such activity. The Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) Scientific Collaboration (LSC) and Virgo Collaboration announced the discovery in two papers published September 2, 2020, in the journals Physical Review Letters and Astrophysical Journal Letters.

The scientists identified the merging black holes by detecting the gravitational waves—ripples in the fabric of space-time—produced in the final moments of the merger. The gravitational waves from GW190521 were detected on May 21, 2019, by the twin LIGO detectors located in Livingston, Louisiana, and Hanford, Washington, and the Virgo detector located near Pisa, Italy.

“The mass of the larger black hole in the pair puts it into the range where it’s unexpected from regular astrophysics processes,” said Peter Shawhan, a professor of physics at UMD, an LSC principal investigator and the LSC observational science coordinator. “It seems too massive to have been formed from a collapsed star, which is where black holes generally come from.”

The larger black hole in the merging pair has a mass 85 times greater than the sun. One possible scenario suggested by the new papers is that the larger object may have been the result of a previous black hole merger rather than a single collapsing star. According to current understanding, stars that could give birth to black holes with masses between 65 and 135 times greater than the sun don’t collapse when they die. Therefore, we don’t expect them to form black holes.

“Right from the beginning, this signal, which is only a tenth of a second long, challenged us in identifying its origin,” said Alessandra Buonanno, a College Park professor at UMD and an LSC principal investigator who also has an appointment as Director at the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics in Potsdam, Germany. “But, despite its short duration, we were able to match the signal to one expected of black-hole mergers, as predicted by Einstein’s theory of general relativity, and we realized we had witnessed, for the first time, the birth of an intermediate-mass black hole from a black-hole parent that most probably was born from an earlier binary merger.”

GW190521 is one of three recent gravitational wave discoveries that challenge current understanding of black holes and allow scientists to test Einstein’s theory of general relativity in new ways. The other two events included the first observed merger of two black holes with distinctly unequal masses and a merger between a black hole and a mystery object, which may be the smallest black hole or the largest neutron star ever observed. A research paper describing the latter was published in Astrophysical Journal Letters on June 23, 2020, while a paper about the former event will be published soon in Physical Review D.

“All three events are novel with masses or mass ratios that we’ve never seen before,” said Shawhan, who is also a fellow of the Joint Space-Science Institute, a partnership between UMD and NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. “So not only are we learning more about black holes in general, but because of these new properties, we are able to see effects of gravity around these compact bodies that we haven't seen before. It gives us an opportunity to test the theory of general relativity in new ways.”

For example, the theory of general relativity predicts that binary systems with distinctly unequal masses will produce gravitational waves with higher harmonics, and that is exactly what the scientists were able to observe for the first time.

“What we mean when we say higher harmonics is like the difference in sound between a musical duet with musicians playing the same instrument versus different instruments,” said Buonanno, who developed the waveform models to observe the harmonics with her LSC group. “The more substructure and complexity the binary has — for example the masses or spins of the black holes are different—the richer is the spectrum of the radiation emitted”

In addition to these three black hole mergers and a previously reported binary neutron star merger, the observational run from April 2019 through March 2020 identified 52 other potential gravitational wave events. The events were posted to a public alert system developed by LIGO and Virgo collaboration members in a program originally spearheaded by Shawhan so that other scientists and interested members of the public can evaluate the gravity wave signals.

“Gravitational wave events are being detected regularly,” Shawhan said, “and some of them are turning out to have remarkable properties which are extending what we can learn about astrophysics.”

The video above shows a numerical simulation of two black holes that spiral inwards and merge, emitting gravitational waves. The simulated gravitational wave signal is consistent with the observation made by the LIGO and Virgo gravitational wave detectors on May 21st, 2019 (GW190521). Copyright © N. Fischer, H. Pfeiffer, A. Buonanno (Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics), Simulating eXtreme Spacetimes (SXS) Collaboration.

Quelle: University of Maryland