2.09.2020

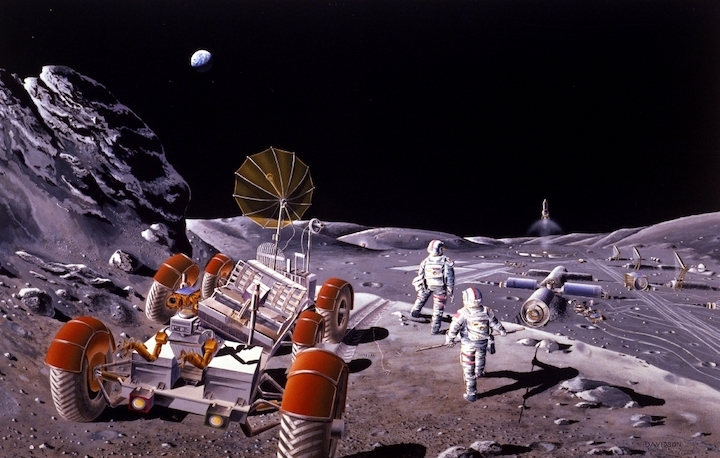

The 2019 movie Ad Astra had a US military base on the moon and a memorable battle scene involving a moon rover, implying that by late this century the moon will be heavily militarised. A question now being discussed in space policy circles is whether fact will follow science fiction, as the US Space Force considers exactly what its role will be. It has some pretty ambitious ideas, and a recent report indicates that its thinking will be shaped by a deep astrostrategic perspective.

So it wasn’t much of a surprise when news emerged that a group of US Air Force Academy cadets are researching the idea of military bases on the lunar surface. The academy’s Institute for Applied Space Policy and Strategy has a ‘military on the moon’ research team that was set up ‘to evaluate the possibility and necessity of a sustained United States presence on the lunar surface’. The focus seems to be on a military base, though there’s little information on exactly what they’re planning.

But the very notion of a military base on the moon has the space law community understandably seeing red.

Such a base would directly conflict with both the spirit and letter of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty (OST), which provides the foundation for space law. Article IV of the treaty states that:

The Moon and other celestial bodies shall be used by all States Parties to the Treaty exclusively for peaceful purposes. The establishment of military bases, installations and fortifications, the testing of any type of weapon and the conduct of military manoeuvres on celestial bodies shall be forbidden.

A military base on the moon would also violate the 1979 Moon Treaty, which Australia supports, though no major space power has ratified it. So that means no overt or declared lunar military bases, at least as long as all powers remain signatories to the OST.

The academy cadets would no doubt be aware of this. Why even consider such a move, then?

Current space law was developed for a different, more benign era and doesn’t adequately address the emerging dynamics of space activities. The framework has gaps that that an adversary could exploit in grey zones in coming decades. In particular, commercial space operations provide a convenient cover for states that wish to creep around international space norms and sidestep established law.

The OST doesn’t prohibit military personnel from being on the moon for scientific ‘or any other peaceful purposes’, and states that ‘the use of any equipment or facility necessary for peaceful exploration of the moon and other celestial bodies shall also not be prohibited’. That implies that a commercial facility supposedly established for peaceful exploration could be staffed by military personnel. Because the treaty leaves a facility’s role wide open to interpretation, a thin veneer could separate a commercial base from an undeclared military facility. A classic example of this problem exists here on earth—in Antarctica.

The OST does require signatories to ensure that they or their commercial representatives conform with Article IV: ‘States Parties to the Treaty shall bear international responsibility for national activities in outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, whether such activities are carried on by government agencies or by non-governmental entities.’

That sounds good, but the clarity dissipates when future commercial space activities are considered in more depth in the light of recent developments in space law. The 2015 US Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act sets a precedent for potential grey zones over legitimate activity by permitting a commercial company to secure, own and profit from a space resource.

The act explicitly states this doesn’t allow a company to claim sovereignty, and thus avoids a challenge to the OST’s provision that, ‘Outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means.’

Yet it’s unclear how a private company will see securing and profiting from a resource as compatible with not controlling the region of a celestial body on which the resource is found. Safeguarding access to a resource—and preventing a competitor from intruding in the region being exploited—implies a security dimension that the OST wasn’t designed to manage.

In April, US President Donald Trump signed an executive order on ‘encouraging support for the recovery and use of space resources’ which said that ‘it shall be the policy of the United States to encourage international support for the public and private recovery and use of resources in outer space, consistent with applicable law’.

The administration then released the Artemis Accords, which are designed to establish a common set of principles to govern the civil exploration and use of outer space. The accords make clear that ‘all activities [on the moon] will be conducted for peaceful purposes, per the tenets of the Outer Space Treaty’. That tends to reinforce the role of the OST, at least for the US and its allies and partners in space.

The Artemis Accords require the US and its partners to share information on the location and general nature of operations so that ‘safety zones’ can be created to ‘prevent harmful interference’ . That implies delineation of territory or a zone of control around a facility.

Space is a global commons that is rich in resources, and major-power competition—as well as commercial competition—is already happening and will intensify in coming decades. It seems likely that, despite the OST, states and non-state actors will compete for access to and control over resources in space. And achieving that access and control will require a permanent presence in the region where the resources are located.

The messy debate over how the commercial and astropolitical realities sit with the OST’s vision of space as a peaceful sanctuary and commons open to all is just getting started. Lunar military bases are not inevitable, but competition for resource wealth on the high frontier is.

Quelle: THE STRATEGIST