23.05.2020

Despite early expectations Comet SWAN appears to be fizzling, providing yet another opportunity to appreciate what makes these objects so unique.

Comet SWAN (C/2020 F8) makes an appearance at the start of dawn north of Duluth, Minn. on May 19. The photo conveys the comet's small apparent size and blue-green color easily visible in a telescope at the time. The trees are motion-blurred because a tracking mount was used to follow the stars. Details: 200mm telephoto at f/2.8, ISO 400, 50-second exposure.

Bob King

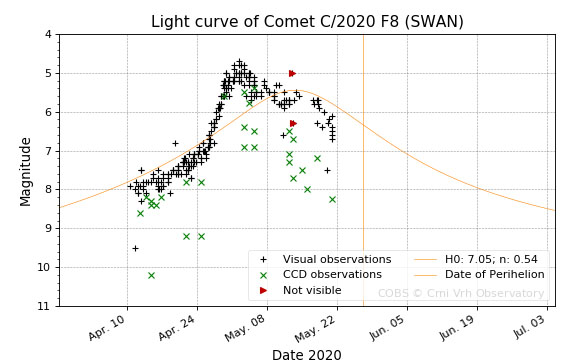

Like you, I waited patiently for Comet SWAN (C/2020 F8). Watched it brighten and develop a beautiful gas tail in April and early May, excited that it was on track to become an easy naked-eye object by mid-May. Southern Hemisphere observers recorded a steady increase in brightness through April, including an outburst at month's end that boosted its magnitude to 5.2. Observers with dark skies reported seeing the comet without optical aid. Even the May 2nd electronic telegram from the International Astronomical Union (IAU) predicted a peak magnitude of 2.8 for SWAN around May 21st. The world was poised with anticipation.

COBS Comet Observation Database / CC BY-NA-SA 4.0

Then it all came to a screeching halt. The comet's brightness stalled and then reversed itself just days before its transition from southern to northern skies. The visual feast we'd expected became a modest morsel instead. SWAN may still have an outburst in the cards, but what I saw at dawn on May 19 — my first swing at the comet — didn't give cause for optimism.

Through 10×50 binoculars it was a small, fuzzy patch of light glowing wanly at magnitude 6.2. While I couldn't detect a tail in the glass, it was obvious in short time-exposure photos. Needless to say, I couldn't see the comet with the naked eye. Through my 15-inch (38-cm), the head shined a beautiful Mediterranean blue with a delicate, broad tail streaming to the west.

Bob King

Clear skies prevailed again on May 21st. I set the alarm half-hoping SWAN would turn around, but when I trained the binoculars on it for the second time I quickly discovered it had faded by another half magnitude. Standing only 7° high at twilight's start it appeared quite faint in binoculars but a 10-inch scope showed a 10′ wide coma and faint tail. The core, which appeared condensed on May 19, looked diluted and washed out, resembling the post-breakup appearance of Comet ATLAS (C/2019 Y4).

Stellarium

As you read this, SWAN is transitioning from the morning to the evening sky, making it easier for many more of us to keep an eye on it. The comet will stand just 5–10° high above the north-northwestern horizon at the end of evening twilight when it's best visible, so be sure to find a spot with a wide-open view in that direction. While it may prove difficult or impossible to see in ordinary binoculars, a telescope will still provide a good view.

Bob King

It's always possible that a cache of fresh ice could lead to another outburst or the nucleus could fragment as it approaches perihelion on May 27th, but don't count on it. Just the same, I encourage you to have a look if only to see what all the fuss is about. If clouds or an obstructed horizon make this impossible, our friend Gianluca Masi will feature live views of the comet on his Virtual Telescope site on May 27th starting at 19:00 UT (3 p.m. EDT).

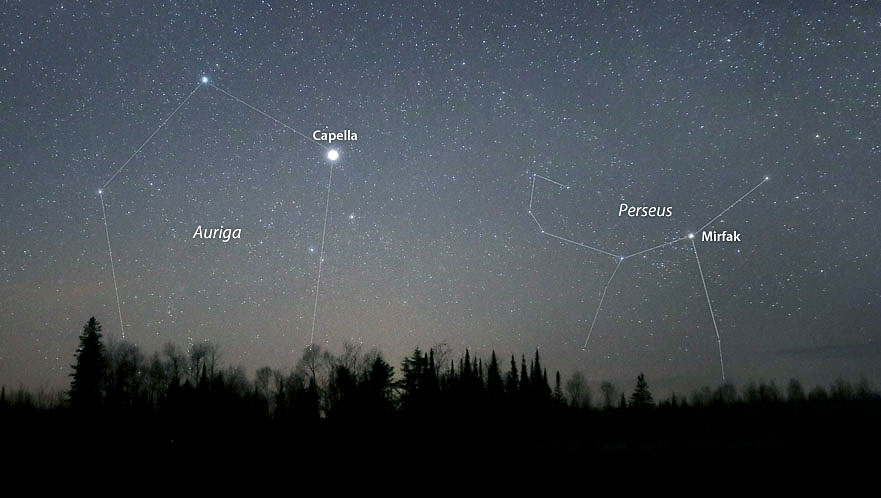

Before the current fading episode, SWAN was expected to slowly dim during the final week of May while en route toward the bright star Capella — a most helpful sky guide.

FIZZLE AND FADE

So why did the comet stall and fade? SWAN is a newcomer to the inner solar system, having arrived after a multi-million year journey from the Oort Cloud. Nascent ices of nitrogen, carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide in its nucleus rapidly vaporized on approach to the Sun, causing the comet to brighten rapidly and leading us to think the trend would continue. Once those ices were used up, the light curve flattened.

While that's the most likely explanation, it's also possible the nucleus underwent fragmentation. Claudio Martinez of the Fundación AZARA de Historia Natural in Argentina ,along with Argentine amateur Victor Buso, took close-ups of the comet's core on May 8th that appear to show a double nucleus. They're still waiting for their results to be confirmed.

Over the years I've learned not to complain about comets even when they "underperform." They are what they are — volatile, unpredictable, fragile — and refreshingly innocent of expectations.

Quelle: Sky&Telescope