5.05.2020

Around the planet, a loosely knit but closely woven band of amateurs monitor the whereabouts of satellites — be they secretive spacecraft, robotic space drones, rocket stages, orbital debris or lost-in-space planetary probes.

But what's the motivation behind this group of sky prowling spirits? What kind of tools are they using now or in the future to purge secrets from space — at times revealing what some countries don't want others to know about?

Space.com reached out to a small set of these hobbyists that contribute to SeeSat-L, a mailing list intended to facilitate rapid, reliable communications among a worldwide cadre of visual satellite observers.

No formal organization

Ted Molczan is a Toronto-based amateur satellite observer. He said that there is no formal organization of satellite onlookers — no leader or board of directors. There are no assigned roles or responsibilities.

The most common activities, Molczan said, are observing, analyzing observations to update the whereabouts of space objects, devising strategies to find newly launched satellites, writing computer software and attempting to resolve the mission of satellites based on their orbits and other information gleaned from open sources.

"Participants decide which of these activities to pursue based on their interest. It is common to wear more than one hat," Molczan said, and explains that the field has made great progress in recent decades.

Secret orbits

In the mid-1990s, satellite sleuths began to use small telescopes to find and track secret objects orbiting Earth at geosynchronous altitude, about 22,236 miles (35,786 kilometers) above the equator, where satellites match the speed of the Earth's rotation.

By 2010, the efforts of the amateurs and the professional International Scientific Optical Network had resulted in the identification of every single large object known to have been launched into a secret geosynchronous orbit since 1968. In 2006, amateurs began to track satellites in secret orbits by measuring and analyzing the Doppler shift of their radio signals, or changes in the frequencies of the radio waves caused by the relative motion of the observer and the satellite.

"Today, this potent technique is a key tool in the amateur kit," Molczan said. "Amateurs contribute to public knowledge. By tracking objects in secret orbits, they provide independent information on the activities of governments in orbit, and expose the practical limits to secrecy."

Eyes-on observations

Amateur interest is not limited to secret satellites. To this point, Molczan flags a list of "eyes-on" assists from citizen satellite trackers.

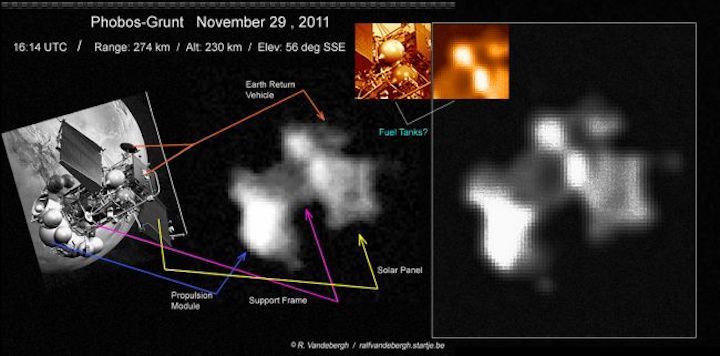

Molczan said that in 2011, Russia sought the assistance of amateurs to track its ill-fated Phobos-Grunt mission during the spacecraft's planned burn to escape Earth orbit, after which it crashed into the Pacific Ocean.

When the probe became stuck in low-Earth orbit after launching on what was supposed to be a mission to retrieve a soil sample from Mars' moon Phobos, satellite tracker Thierry Legault obtained high-resolution video imagery of the stranded spacecraft with useful information on its orientation. Amateur orbit analysis revealed a series of unusual maneuvers by the doomed spacecraft, Molczan added, that could potentially have aided in determining the cause of the failure.

In 2015, radio and optical tracking by amateurs assisted The Planetary Society to track its LightSail satellite.

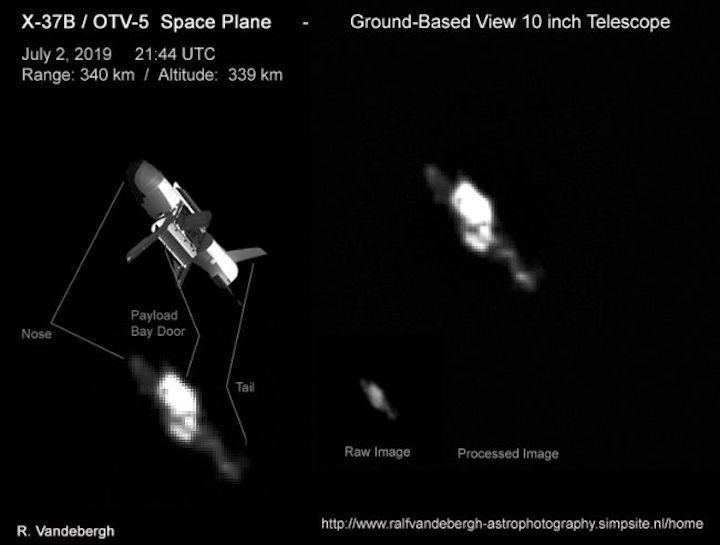

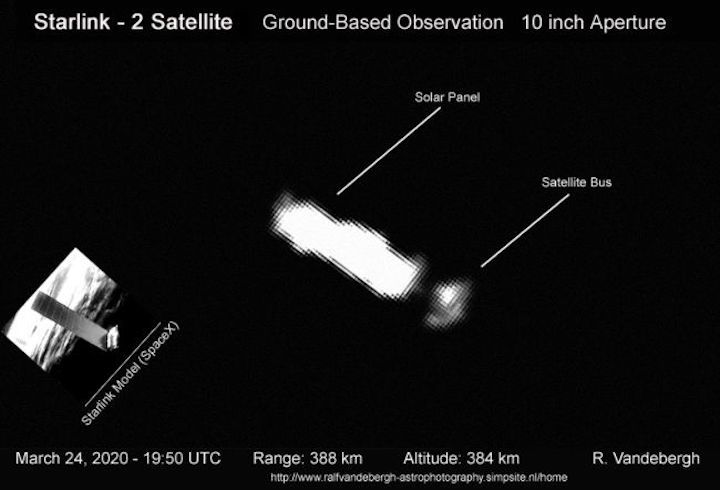

Currently, amateurs are heeding the call of professional astronomers for data on the brightness of SpaceX's Starlink satellites to determine their potential to ruin imagery obtained by Earth-based telescopes. For example, Ralf Vandebergh, a Dutch astronomer, professional photographer and veteran satellite spotter has dedicated considerable time to monitoring the growing Starlink constellation.

As for the future growth of satellite watching, it's impossible to forecast, Molczan said, but it is reasonable to expect amateurs to continue to exploit advanced technology that is within their grasp. Fully automated image acquisition, data reduction and orbital analysis is one possibility, he said.

"High-tech will not appeal to everyone. Fortunately, low and high-tech can be expected to continue to coexist. Observers who prefer to get out under the stars will still be able to contribute usefully using the traditional binoculars and stop-watch method," Molczan concluded.

Moonwatch to today

Mike Waterman of the United Kingdom saw his first satellite, Sputnik 2, in 1958, and a few years later joined a UK-based satellite watching group that provided predictions of spacecraft flyovers.

Waterman recalled that at that time there were three such groups, one based in the UK, one in the USSR and another in the U.S. called "Operation Moonwatch," which was an amateur science program formally initiated by the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Cambridge, Massachusetts and organized as part of the 1957-1958 International Geophysical Year, which was a worldwide cooperative effort to gather scientific data about the Earth.

"Observations were gathered and used for scientific and other purposes," Waterman said, "in particular gravity harmonics, upper air density and upper atmosphere winds. Communication was mostly by post, rarely by telephone, and observing was done primarily with binoculars, star atlases (on paper) and mechanical stopwatches."

Waterman points with pride to the time when he started doing his own predictions, and an early highlight was observing the rocket stages for Apollo missions 8, 10 and 12, going towards the moon.

"I got my first computer in 1983 and within a few weeks I was using it for predictions. By 1985 I had part of a star atlas on my computer, so [I] was avoiding most errors in satellite positions," Waterman said. "Undoubtedly the most important change was the internet and email. Suddenly, for me in 1999/2000, you could send and receive orbits, observations and opinions anywhere, almost for free!"

New skills and strategies

Brad Young of Tulsa, Oklahoma is a highly active observer. In recent years, he has augmented his sharp-eyed skills by means of remote telescopes that enable him to observe geosynchronous satellites that never rise above his horizon. He uses half a dozen cameras, located in Spain, Australia, New Mexico and California.

"The future is bright," Young said. "Active development of phone app tracking and reporting systems are happening to enlist a global team of observers." As example, he pointed to TruSat, a citizen-powered, open source system for creating a globally-accessible record of satellite orbital positions.

Along with this, Young said that skywatching training is being upgraded to inform the general public and excite their interest in tracking satellites. "The sea change will be involving more people," he said, emphasizing that crowdsourcing visual observations with mobile apps will be crucial.

"Imaging systems and analysis tools are becoming accessible to more people and can provide amazing results in finding lost objects and checking on [satellite] maneuvers and conjunctions," Young said. "Remote imaging networks give global coverage. Open, timely collaboration between analysts will promote understanding how and why orbits change."

Young said that he sees new skills and strategies popping up "to make people aware of the issues with our orbital infrastructure, and how they can help, but also exciting them to get out and observe."

Shed some light

A professional archeologist, Marco Langbroek is deeply interested in meteors and satellites and works in the astronomy department at Leiden University in The Netherlands. He does extensive research into secret satellites, and publishes his findings on his blog and is a consultant on Space Situational Awareness issues to the Space Security Center of the Royal Dutch Air Force.

"I think there have always been great observing and analysis skills within the amateur community, but over the last decade or so it has become more publicly visible through blogs, Facebook, Twitter etc. As a result, the press knows how to find us more easily as well, and has come to recognize our skills."

Regarding the overall value of the worldwide amateur observers, Langbroek paints a big picture.

"Over the past decades, space technology has taken a very important role in our society, often without people realizing it. Our modern economies highly depend on space technology, like logistic networks, trade and communications. Same for the modern military as space assets play an increasingly important role there. And important geopolitical decisions are made based on intelligence gathered from space," Langbroek said.

That makes us vulnerable as a society, he added. "Thus, what happens up there is of prime importance to our society. At the same time, a part of what happens in space remains hidden, because it concerns classified space programs. The amateur satellite watchers serve to shed some light onto that otherwise unknown aspect of space that otherwise would go without public scrutiny, while having a very large impact on our lives," Langbroek said.

Wider relevance

Similar in view to other satellite watchers, Langbroek said that the technological revolution that transformed much of our society has had its impact on the observing prowess of skywatchers. More high-tech equipment (cameras notably) have become available, as well as more computer power. The internet has provided much better access to data sources, books, articles and other sources over the past two decades or so, he said, and it has made contacts and cooperation between members of a far-flung group much more easy.

In looking into the future, Langbroek said that automatic, near real-time detection, recognition, characterization and orbital determination of satellites in the sky is one development that is already in the making.

"I also think that third parties — commercial and government — are already and increasingly will be starting to take more interest in the skills and data we have obtained," Langbroek concluded. "So from a bunch of hobby nerds in a very esoteric niche, we are drawn into a wider, more professional world and a wider relevance to our society."

Quelle: SC