19.03.2020

Scientists say lunar explorers could ‘see’ enough Earth-orbiting satellites to make an expensive new system unnecessary

If astronauts reach the moon as planned under NASA’s Project Artemis, they’ll have work to do. A major objective will be to mine deposits of ice in craters near the lunar south pole—useful not only for water but because it can be broken down into hydrogen and oxygen. But they’ll need guidance to navigate precisely to the spots where robotic spacecraft have pointed to the ice on the lunar map. They’ll also need to rendezvous with equipment sent on ahead of them such as landing ships, lunar rovers, drilling equipment, and supply vehicles. There can be no guessing. They will need to know exactly where they are in real time, whether they’re in lunar orbit or on the moon’s very alien surface.

Which got some scientists thinking. Here on Earth, our lives have been transformed by the Global Positioning System, fleets of satellites operated by the United States and other countries that are used in myriad ways to help people navigate. Down here, GPS is capable of pinpointing locations with accuracy measured in centimeters. Could it help astronauts on lunar voyages?

Kar-Ming Cheung and Charles Lee of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California did the math, and concluded that the answer is yes: Signals from existing global navigation satellites near the Earth could be used to guide astronauts in lunar orbit, 385,000 km away. The researchers presented their newest findings at the IEEE Aerospace Conference in Montana this month.

“We are trying to get it working, especially with the big flood of missions in the next few years,” said Cheung. “We have to have the infrastructure to do the positioning of those vehicles.”

Cheung and Lee plotted the orbits of navigation satellites from the United States’s Global Positioning System and two of its counterparts, Europe’s Galileo and Russia’s GLONASS system—81 satellites in all. Most of them have directional antennas transmitting toward Earth’s surface, but their signals also radiate into space. Those signals, say the researchers, are strong enough to be read by spacecraft with fairly compact receivers near the moon. Cheung, Lee and their team calculated that a spacecraft in lunar orbit would be able to “see” between five and 13 satellites’ signals at any given time—enough to accurately determine its position in space to within 200 to 300 meters. In computer simulations, they were able to implement various methods for improving the accuracy substantially from there.

Helping astronauts navigate after landing on the moon’s surface would be more complicated, mainly because in polar regions, the Earth would be low on the horizon. Signals could easily be blocked by hills or crater rims.

But the JPL team and colleagues at the Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland anticipated that. To help astronauts, the team suggested using a transmitter located much closer to them as a reference point. Perhaps, the scientists wrote, they could use two satellites in lunar orbit—a new relay satellite in high lunar orbit to act as a locator beacon, combined with NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, which has been surveying the moon since 2009.

This mini-network need not be terribly expensive by space-program standards. The relay satellite could be very small, take design cues from existing satellite designs, and ride piggyback on a rocket launching other payloads toward the moon ahead of astronauts.

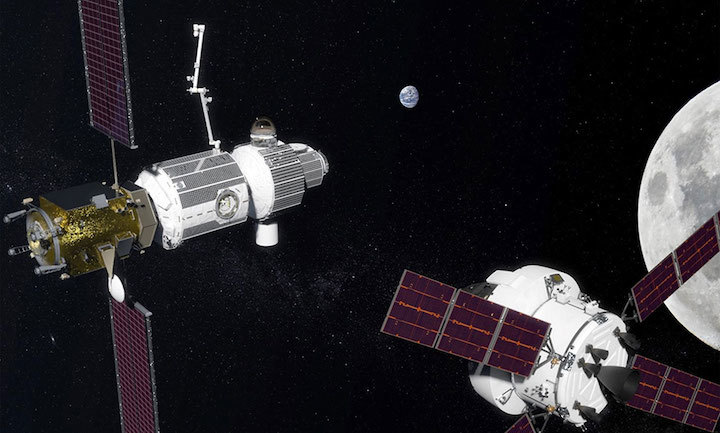

The plans for Artemis have been in flux, slowed by debates over funding and mission architecture. NASA managers have been banking on a planned lunar-orbiting base station, known as the Gateway, to make future missions more practical. But if they are going to put astronauts on the surface of the moon by 2024, as the White House has ordered, they say the Gateway may have to wait until later in the decade. Still, scientists say early plans for lunar navigation will be useful, no matter how lunar landings play out.

“This can be done,” said Cheung. “It’s just a matter of money.”

Quelle:IEEE