4.02.2020

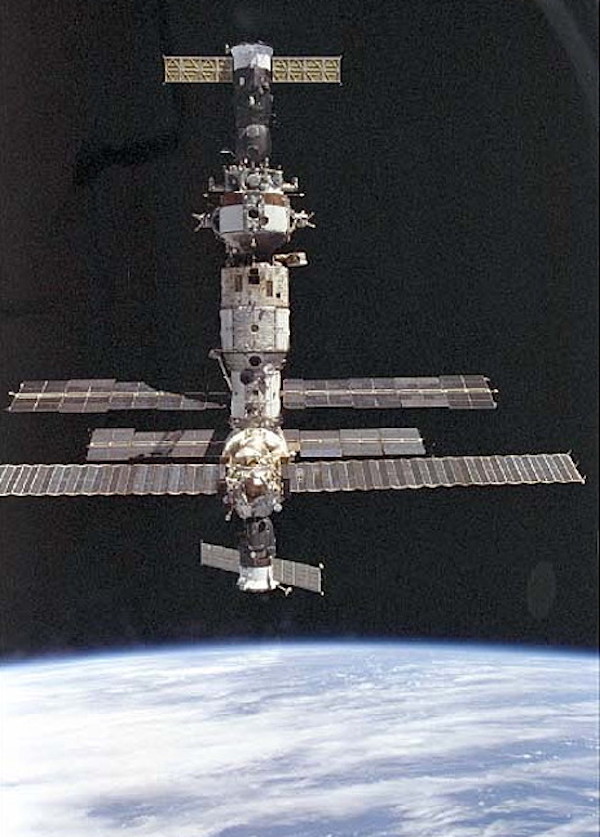

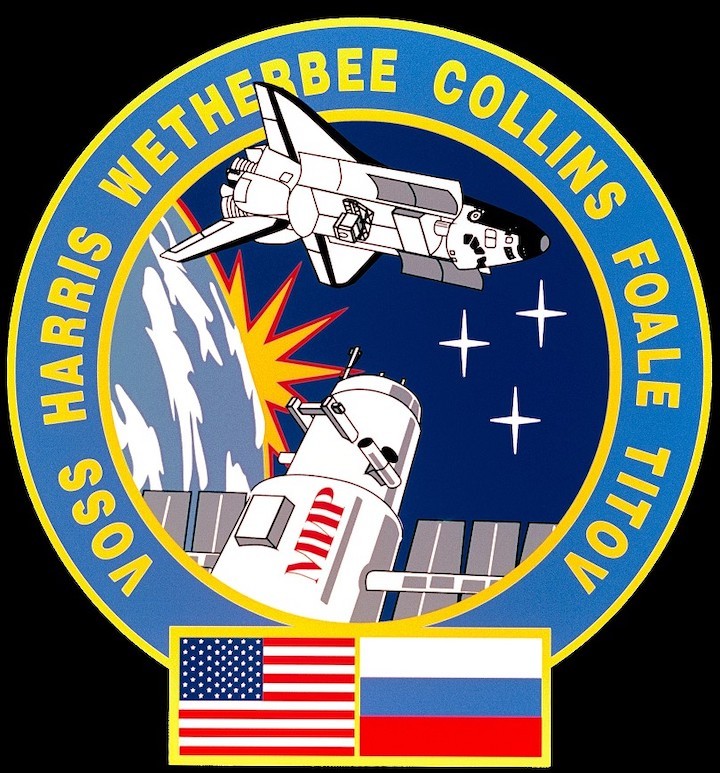

A quarter-century ago this month, in February 1995, the astronauts (and a single cosmonaut) of shuttle Discovery roared into the night on a mission which performed the first rendezvous with Russia’s Mir space station. During their eight days in space, the men and women of STS-63—Commander Jim Wetherbee, Pilot Eileen Collins and Mission Specialists Bernard Harris, Mike Foale, Vladimir Titov and the late Janice Voss—approached to within 33 feet (10 meters) of the iconic orbital outpost, which would host several U.S. long-duration residents and no fewer than nine visiting shuttle crews between 1995 and 1998.

Yet STS-63 encompassed far more than that, with scientific research in a pressurized laboratory in Discovery’s payload bay, deployment and retrieval of a free-flying solar physics satellite, the first spacewalk by British and African-American astronauts and the first female pilot of the shuttle era.

When the STS-63 crew was announced in late 1993, they could hardly have imagined that theirs was a voyage of destiny. Scheduled to launch in May 1994, the inclusion of Titov made this the second shuttle mission to include a Russian cosmonaut, part of a co-operative venture between the two former foes which would culminate in the construction of the International Space Station (ISS). But in September 1993, a series of high-level agreements between U.S. Vice President Al Gore and Russian Prime Minister Viktor Chernomyrdin led to STS-63 being selected to demonstrate the shuttle’s capacity to rendezvous with Mir and test radio communications and navigation equipment. At first, the plan was for Wetherbee and Collins to fly Discovery close to Mir and STS-63’s inclination was changed from 28.5 degrees to the 51.6-degree orbital “tilt” of the station.

By this time, STS-63 had slipped to early 1995, in part because the experiment load for its Spacehab-3 pressurized lab was relatively light. The Mir rendezvous commitment initially required Wetherbee to fly no closer than 1,100 feet (330 meters) from Mir, although U.S. and Russian trajectory specialists fine-tuned this to 400 feet (120 meters) and eventually just 110 feet (33 meters). But Wetherbee felt that the systems his crew needed to test—procedures, tracking radar, hand-held laser rangefinders and cameras—would be largely ineffective at great distance. “The first thing I noticed,” he recalled in an interview, “was that…the visual target that we used couldn’t be used accurately until we got to about 30 feet.” Wetherbee’s argument eventually won the backing of NASA management, but the Russians proved harder to convince, particularly as STS-63 offered little discernible benefit in terms of delivering crew or cargo to Mir. Eventually, it was agreed that Wetherbee would rendezvous to 33 feet (10 meters).

It was made clear on both sides that he would approach no closer. “I was not going to violate that limit, by even a single centimeter,” said Wetherbee, “because I knew both space agencies in both countries were going to be watching as we approached on this flight.”

By the dawn of 1995, the launch of Wetherbee’s mission had slipped until no earlier than 2 February. Russian planners insisted that the rendezvous had to occur whilst Mir was in contact with Russian ground stations, which demanded that the shuttle’s final approach had to occur during orbital darkness. Although the rendezvous—which had by now earned the media moniker “Near-Mir”—on Flight Day Four was the most publicly visible part of STS-63, the mission also featured 20 experiments aboard the Spacehab-3 module, whose flat roof carried a pair of 12-inch-diameter (30 cm) windows, one of which housed a NASA docking camera to assist with proximity operations.

Launch on the 2nd was postponed by 24 hours, due to the failure of one of Discovery’s three Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs), which was replaced and tested. The launch window was particularly tight at just five minutes, and the precise launch time was decided relatively late in the countdown, based on new Mir state vectors for the shuttle rendezvous phasing requirements. These were updated about 60 minutes before launch, and the STS-63 crew rocketed away from Pad 39B at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) at 12:22:03 a.m. EST on 3 February, turning night into day across the marshy Florida landscape.

“Pretty rough ride,” Wetherbee recounted at the post-flight press conference. “Seven and a half million pounds of thrust…and you can feel every one of those pounds.”

Within nine minutes, Discovery reached her preliminary orbit, although not without incident, for one of her aft-mounted Reaction Control System (RCS) thrusters failed and another exhibited a minor, but persistent leak. As soon as the External Tank (ET) was jettisoned, Wetherbee and Collins were alerted by a “Jet Leak” and two “Jet Off” RCS messages. The shuttle was equipped with 44 primary and backup RCS thrusters on its nose and aft compartment, which were required primarily for orbital maneuvering. Two aft-mounted thrusters had failed, one on the port side (L2D) and one on the starboard (R1U). The former was “deselected” and remained off for the rest of the flight, but R1U was a primary thruster and critical for the Mir rendezvous commitment.

Wetherbee was dismayed, having trained for more than a year to prepare for STS-71, to see his flight potentially hamstrung within minutes of achieving orbit. “As the day wore on, I was pretty much convinced that we were not going to be able to rendezvous with Mir,” he said, “and it was pretty disappointing.” Although all of the thrusters were fully redundant, flight rules dictated that all aft-firing RCS needed to be operational for the orbiter to advance closer than 1,100 feet (330 meters) from Mir. Later that afternoon, Mission Control asked Wetherbee to position the shuttle to allow the Sun to shine onto the vehicle’s top side and hopefully warm up the leaking thruster, which was losing up to 2 pounds (0.9 kg) of oxidizer per hour. This was less than originally feared, and its temperature of 12.2 degrees Celsius (53.9 degrees Fahrenheit) was stable and well above the minimum redline of 4.4 degrees Celsius (40 degrees Fahrenheit), although if it dipped significantly it would be shut down and any chance of approaching Mir within 1,100 feet (330 meters) would evaporate.

In the meantime, the crew pressed on with their mission. By the time the six spacefarers turned in for bed, Discovery was trailing the station by about 7,000 miles (11,250 km) and closing this distance by about (330 km) per orbit. Over the next three days, Wetherbee and Collins would execute five maneuvers to position the shuttle at a point about 46 miles (75 km) “behind” Mir, ahead of the final manual rendezvous. Bernard Harris activated Spacehab-3—whose payloads included McDonnell Douglas’ Charlotte robot, capable of operating knobs, switches and buttons, as well as exchanging experiment samples and data cartridges, thereby freeing up valuable crew time—and Vladimir Titov grappled the SPARTAN-204 solar physics satellite with Discovery’s Remote Manipulator System (RMS) mechanical arm for a series of observations of the “shuttle glow” phenomenon.

However, the RCS problems continued. The L2D aft thruster had been deselected, but its critical R1U counterpart maintained its minor leak. The problem worsened when one of the forward RCS thrusters in the shuttle’s nose (F1F) also began leaking during a two-part “hot-fire” test on 4 February. At one stage, its temperature fell below the minimum redline, forcing the crew to close its oxidizer supply line and maneuver Discovery into a nose-to-Sun orientation in an effort to warm it up. Efforts were also made to close and reopen its manifold, in the hope that the force of pressurization might push out any contaminants, and F1F was eventually revived.

The ailing R1U in the aft compartment was not so fortunate, however, with no fewer than four fruitless attempts made to bring it back online. By 5 February, the day before the Mir rendezvous, it was still leaking. “You could look out the back window and you could see the propellant going up for miles,” Wetherbee recalled. “It kind of goes in a cone-shaped pattern, because there’s no atmosphere to attenuate its motion, and it just goes up pretty straight and it just continues, like a snowstorm.” The risk of contaminating Mir was very real, not only in terms of the station’s fragile solar arrays, but also the delicate optical sensors of the Soyuz TM-20 spacecraft, which would ferry cosmonauts Aleksandr Viktorenko, Yelena Kondakova and Valeri Polyakov back to Earth in late March.

Although the rendezvous to 33 feet (10 meters) was still officially on, Wetherbee remained uneasy. He pulled Titov to one side. “You know, if this leak doesn’t get any smaller, I will not bring our vehicle close to Mir,” he told the cosmonaut, “even if they give us a Go, because I don’t want to cause any problems for the cosmonauts when they’re coming back.” Indeed, 6 February 1995 would be a day of truth for both the shuttle, Mir, and the new partnership between the two nations.

The second part of this article will appear next..

Quelle: AS