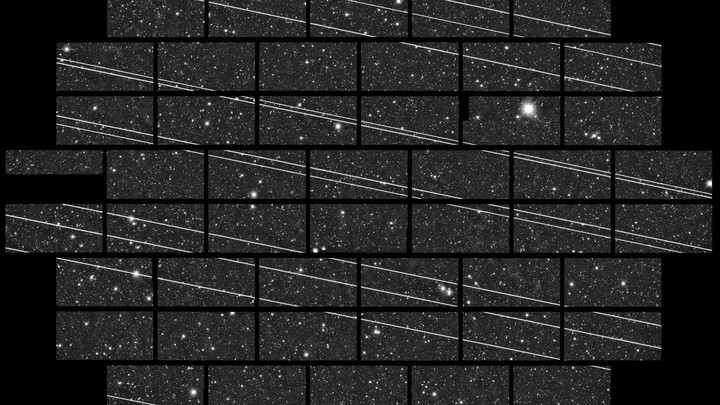

Some astronomers say that SpaceX should stop launching Starlink satellites until engineers find a fix for their brightness, while others, including Seitzer—who is working with SpaceX engineers—say the optical-astronomy community could probably live with about 1,500 of them. Well beyond that, dodging bright satellites and capturing good, unblemished data would become harder.

“We can’t wait for the regulations, for new rules to be drafted, for the comment periods,” Seitzer says. “We have to work with the companies right now to try to convince them of the value of making their satellites as faint as possible.”

The FCC has approved the launch of 12,000 Starlink satellites so far, and SpaceX wants to launch 30,000 more. (The agency did not respond to questions about whether it should be responsible for controlling the brightness of satellites.) By the end of this year, the company’s operational satellites in orbit could outnumber all other satellites combined. That would be a tremendous, wholesale change to the night sky; one company in one country would have made an immense impact on a borderless piece of nature that everyone on Earth can access. But when SpaceX filled out its application to the FCC, it marked “No” on a question asking whether the project would have “a significant environmental impact”—which meant there was no review of the satellites’ potential effects. Perhaps the surprisingly bright appearance of the Starlink satellites in the night sky, which astronomers could argue counts as an environmental impact, could have been known before launch.

It might seem easy to wave away astronomers’ concerns as the hand-wringing of a small group. A couple hundred shiny satellites have little to no bearing on the daily lives of most people, who already can’t see the night sky as it truly is, because of artificial-light pollution. Aside from coordinating with commercial companies directly, it’s unclear what astronomers can do either. They doubt that average citizens are going to call their congressperson about Starlink satellites. They could sue the FCC and perhaps force the agency to consider environmental reviews, as the American Bird Conservancy did when it became apparent that the lights on communication towers could disorient migratory birds. As Jessica Rosenworcel, an FCC commissioner, saidherself last year, when the agency approved the Starlink constellation: “This rush to develop new space opportunities requires new rules. Despite the revolutionary activity in our atmosphere, the regulatory frameworks we rely on to shape these efforts are dated.”

Stanek’s point, illustrated by his neighbor’s shed, is that mega-constellations alter the aesthetics and value of the night sky in an unavoidable way. “We can’t opt out,” he said. “If I get sick and tired of living in Columbus, Ohio, I could move out to a remote cabin and disconnect from the internet. But here, everybody on the entire Earth that ever wants to look at the sky has to look at the Starlink satellites.” Obviously not everyone can pick up and relocate to the woods to experience the unobscured beauty of the sky. But there still are, for now, places where you’d expect not to see artificial stars passing overhead.

Quelle: The Atlantic