11.01.2020

The surprising find could help researchers better understand why modern Mars is a desert world.

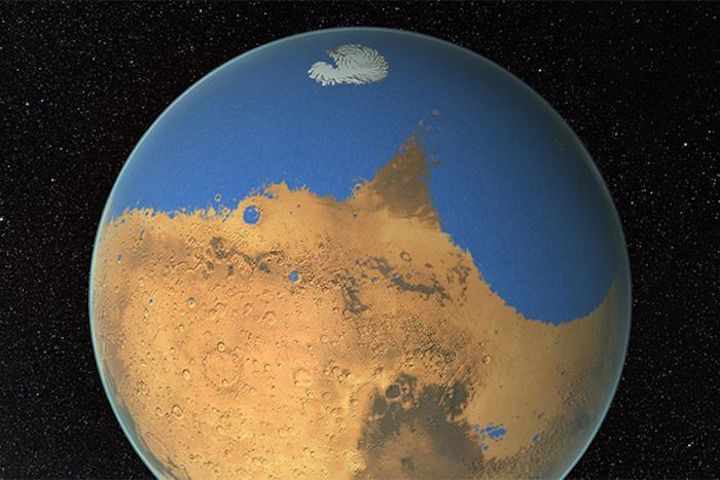

Artist's impression of a primitive ocean on Mars, which some researchers suggested harbored more water than the Arctic Ocean on Earth. (Most of that water was later lost to space.)

Water might escape Mars more effectively than previously thought, potentially helping to explain how the Red Planet lost its seas, lakes and rivers, a new study finds.

Although Mars is now cold and dry, winding river valleys and dry lake beds suggest that water covered much of the Red Planet billions of years ago. What remains of the water on Mars is mostly locked frozen in the Red Planet's polar ice caps, which possess less than 10% of the water that once flowed on the Martian surface, prior work has suggested.

Previous research has also indicated that Martian water mostly escaped into space. Ultraviolet radiation from the sun breaks apart water in Mars' upper atmosphere to form hydrogen and oxygen, and much of this hydrogen then floats off into space, given its extraordinarily light nature and Mars' middling gravity (which is just 40% as strong as Earth's).

Recent findings suggested that large amounts of water might regularly make rapid intrusions into Mars' upper atmosphere. To shed light on these events, scientists analyzed data from the Mars-circling Trace Gas Orbiter, which is part of the European-Russian ExoMars program. The scientists focused on the way water was distributed up and down the Martian atmosphere by altitude in 2018 and 2019.

The researchers found that seasonal changes were the key factors driving how water vapor was distributed in the Martian atmosphere. During the warmest, stormiest part of the Red Planet's year, for example, large portions of the atmosphere became "supersaturated" with 10 to 100 times more water vapor than its temperature should theoretically allow, allowing water to reach the upper atmosphere. These extraordinary levels of saturation "are observed nowhere on any other body of the solar system," study co-lead author Franck Montmessin, a planetary scientist at the University of Paris-Saclay in France, told Space.com.

The scientists were surprised that such large amounts of water vapor could reach the upper atmosphere. Previously, they expected "it should have been limited by the cold temperature up above and be bound to condense into clouds," Montmessin said.

All in all, if water vapor can regularly float so high into the Martian atmospherewithout being limited by condensation, "we might envision that water escape on Mars has been more way more effective than previously thought," Montmessin said.

Future research can better quantify how much water is entering the upper atmosphere and model its behavior, so scientists can better understand how the water vapor may escape into space, Montmessin said.

The scientists detailed their findings online today (Jan. 9) in the journal Science.

Quelle: SC