.

Analysis of radar data hints that Mars may still be geologically active.

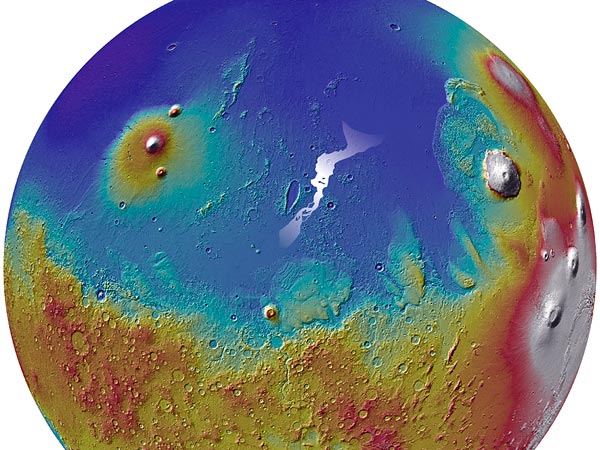

The Marte Vallis channel system (white area, center) on Mars.

.

Evidence of a megaflood on Mars—a surprisingly recent one that cut a 600-mile (966-kilometer) river channel into the planet—has been detected by radar from an orbiting satellite.

Scientists have known for some time about the existence of the Marte Vallis channel system. But the new radar research has doubled the estimated depth of the massive flow and identified the headwaters and floodplain of the river. Both had been covered by lava from a volcanic eruption no more than 500 million years ago.

The megaflood and volcano are considered especially significant because they occurred so recently, in geological terms, suggesting that Mars may well remain a geologically active planet today. (Learn about Martian geology.)

Before a new picture of Mars began to emerge over the past decade, the planet was considered to have been cold, dry, and largely geologically dead for more than three billion years.

"What we've found is that the source of this megaflood was water deep underground that was delivered to the surface through tectonic fractures," said Gareth Morgan of the Smithsonian Institution's Air and Space Museum, one of several authors of the article appearing today in the journal Science.

"The source of the water, and the size of the outflow, had been something of a mystery, but the radar allowed us to look below the lava flows and see what existed there before," he said.

Earthly Analogue

Morgan likened the scale of the Marte Vallis flood to that of the Missoula outpourings of some 15,000 years ago in the Pacific Northwest. After the breaking of an ice dam at glacial Lake Missoula, the water surged westward and flooded large areas of what is now Washington and Oregon. These events would have drained the 200-mile-long (322-kilometer-long) lake in 48 hours.

In both the Missoula floods (which occurred numerous times) and the Marte Vallis megafloods (which appears to have occurred far less frequently), the power of the water dug deep channels into the hardened lava, or basalt.

The paper, which has co-authors from NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, as well as the Southwest Research Institute, is based on years of analyzing data from the Shallow Radar (SHARAD) onboard NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

The radar has been used extensively to investigate the Martian poles, and only more recently have investigators focused on areas such as the equatorial Elysium Planitia, the site of Marte Vallis.

These deep river channels on Mars were formed roughly 3.7 to 3.1 billion years ago. Estimated to run for 600 miles (966 kilometers) or more, these channels are some 60 miles (97 kilometers) wide.

By analyzing the characteristics of the channel, the team concluded that the water flow was 262 feet (80 meters) or deeper, rather than the earlier depth estimate of 131 feet (40 meters).

Watery Revolution

The new finding is part of a recent revolution in water discoveries on Mars. Not only have researchers identified deep river channels, but they've discovered gullies of liquid water that are still forming and streams of salty water that appear to flow down some crater walls during the Martian summer. (Related: "Water on Mars: Exploration and Evidence.")

Following in the tracks of its smaller predecessors, the Mars rover Curiosity has also been searching for signs that surface water used to be present on the planet. It has already identified what scientists say was a river or streambed that once tumbled into Gale Crater. (Related: "Mars Rover Finds Ancient Streambed-Proof of Flowing Water.")

By examining the makeup of some of the rock formations and the many rounded pebbles nearby, the Curiosity team concluded that a fast-flowing stream once came off the crater rim and ran to the area near the rover's landing site. Unlike the megafloods, these smaller rivers or streams are believed to have run for thousands or millions of years, rather than days or months.

"Mars is certainly very cold and dry today, but even now it remains dynamic and certainly is not dead," Morgan said. "There are huge reservoirs of ice beneath the surface and we don't really know much about its relationship with the surface."

But the Marte Vallis finding makes clear that water from deep in the planet can and has surged to the surface through rock fractures in the relatively recent past, he said. And it is within the realm of possibility that something similar could set off another megaflood in the future.

Quelle: National Geographic