15.08.2019

Jupiter may have had a head-on collision with a massive protoplanet

Explains the odd distribution of material found by the Juno orbiter.

Planet-forming disks start out as a mix of dust and gas, but the gas doesn't stick around for long. As the star at their center ignites, the radiation it emits starts driving off the gas, eventually leaving a disk with nothing but dust behind. That creates a narrow window for the formation of gas giants, which have to grow big enough to start sweeping in gas before the star drives it all off.

Our current models suggest that the best way to do this is to start with a large solid body, roughly 10 times the mass of Earth. That's big enough to draw in gas quickly and start a runaway process by which the ever-increasing mass pulls in more material from farther away in the disk. This would suggest that, buried deep below the clouds and layers of metallic hydrogen on Jupiter, there's a solid core that would dwarf the Earth if it were ever stripped of all the material above it.

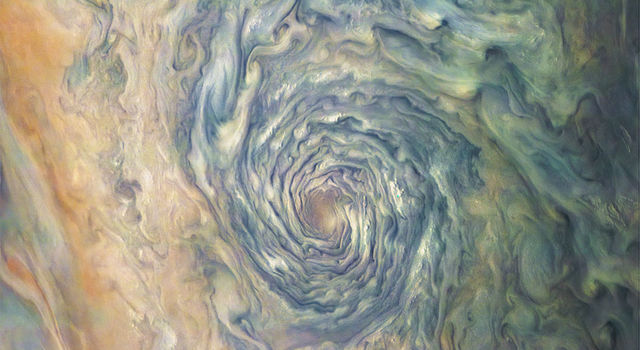

Among other things, the Juno mission was intended to test this idea by studying the gravitational field of the giant planet. But the data it has been sending back suggests something strange is going on inside Jupiter, with more heavy material outside the immediate core area than we'd expect. Now, an international team of researchers is providing a possible explanation: Jupiter's core was shattered by a head-on collision with a massive protoplanet.

What lies beneath

We obviously can't directly image what's going on inside Jupiter. Instead, we have to figure out what's there based on inferences made from the planet's gravitational field. And Juno was the first probe specifically designed to improve our understanding of that gravitational field. While further data is still coming in, a preliminary analysis suggests that one explanation for what we're seeing is that the planet has a core that the new paper describes as "dilute." Instead of the heavier, solid material being concentrated at the core, some of the heavier elements appear to be spread widely across the planet's interior, reaching up to about halfway to the planet's surface.

How that happened is not at all clear, given that we think the only way for a planet like Jupiter to happen is to start with a solid core. It's possible that further Juno data will indicate that a diffuse core is unlikely. Alternatively, our models of planet formation could be wrong. But the researchers start with the premise that everything is correct and that there's something unexpected going on in Jupiter's interior.

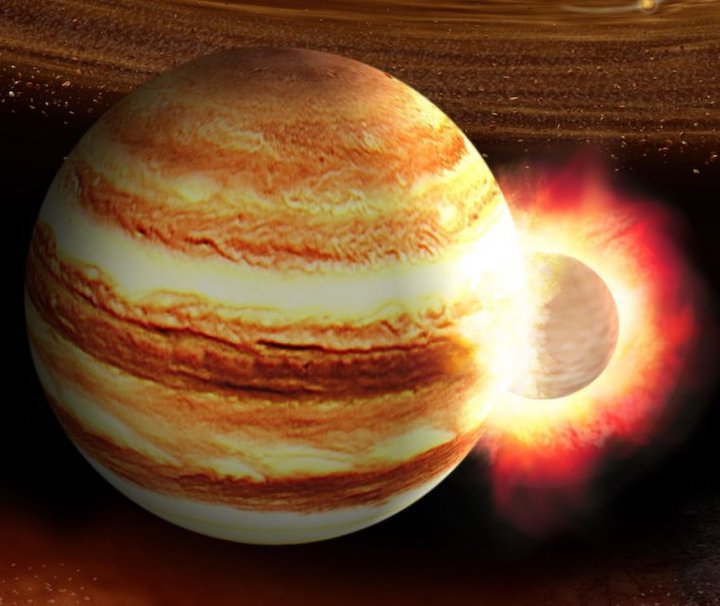

One option is that the metallic hydrogen layer of Jupiter has gradually eroded the core, but we don't know whether metallic hydrogen is capable of that or how heavier elements would mix in it. Instead, the authors consider the possibility that Jupiter's core was disrupted by a collision, much like the one that formed the Earth-Moon system—although completely unlike it in scale.

Collisions could be driven by Jupiter's formation itself. A 10-Earth-mass core is only about 5% of Jupiter's final mass, and the runaway process that surrounded it with gas would have enhanced its gravitational pull by a factor of 30 in less than a million years. Any other bodies nearby could be drawn in to a collision. And since Jupiter's core is thought to have formed via a series of collisions among smaller bodies, there's a reasonable chance there was something nearby that could undergo a collision.

To test this idea, the researchers ran a large number of simulations of the early Solar System, varying the precise configuration of Jupiter and any nearby orbital bodies. They found that in many of these simulations, the growth of Jupiter caused anything nearby to cross orbits, frequently resulting in collisions. Because of the immense pull of Jupiter, most of the collisions ended up being head-on, sending the protoplanet directly to the core of Jupiter.

Core shattering

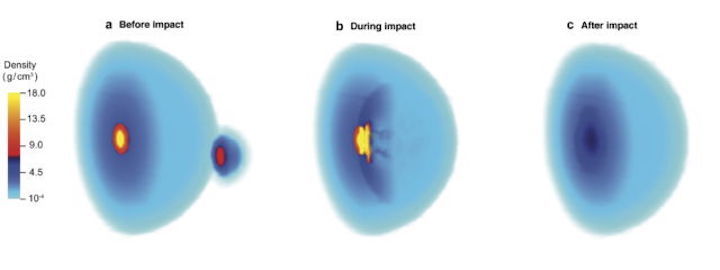

They then turned to a different set of simulations, looking into what happened to the core of Jupiter as a result. The exact details depend on the size of what hits Jupiter and the size of the giant planet at the time of the impact. The simulation they ran in detail involves Jupiter being run into by an eight-Earth-mass core surrounded by two Earth masses of gas. Smaller objects, including Earth-sized protoplanets, would disintegrate in the atmosphere before reaching the core.

Despite the staggering scale of this collision, it only adds a small amount to the total energy delivered to Jupiter during its formation. But it does change the energetics of the core itself, which begins to oscillate. And convection starts bringing the products of these oscillations higher up into the planet's envelope. Within a matter of a few days, Jupiter settles into a state where its core is diffuse and extends nearly half-way to the surface of the planet.

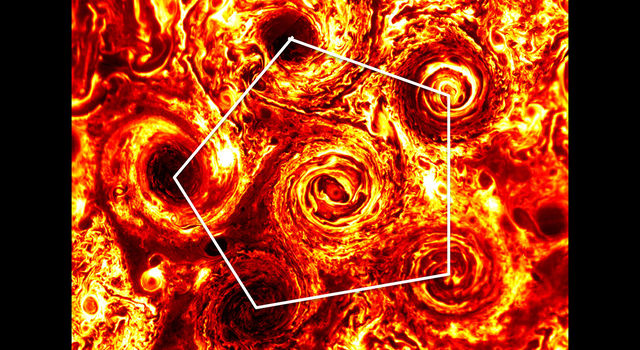

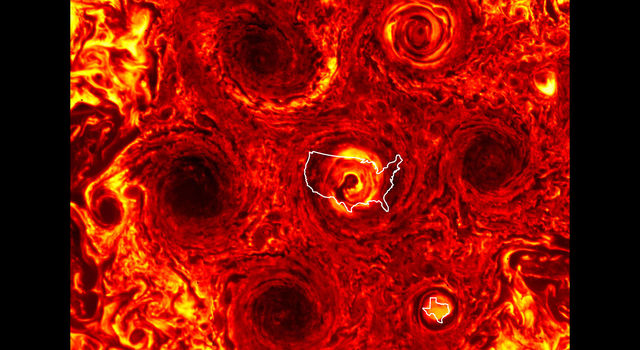

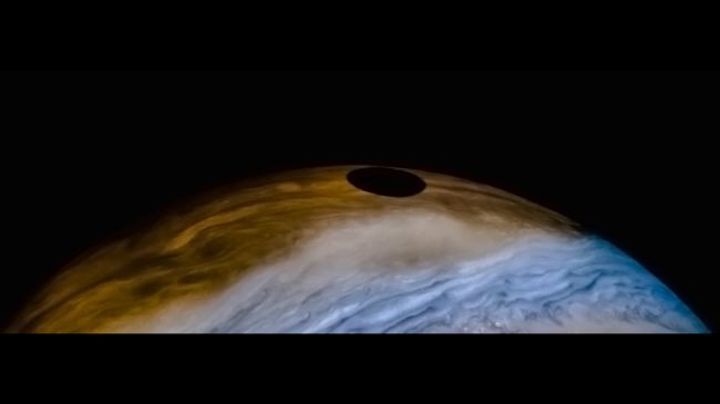

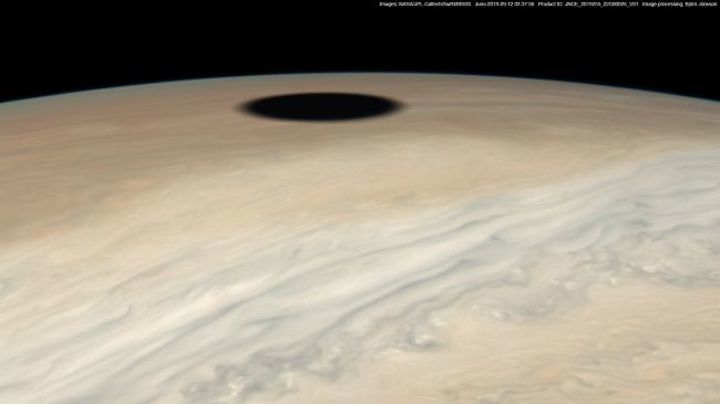

Snapshots of the collision simulation.

Of course, this event occurred over four billion years ago, and it would have to have remained stable for the intervening time to be detected by Juno. The researchers found that this was possible if the internal temperature of Jupiter stabilized at 30,000 Kelvin. Any hotter and convection becomes high enough to eliminate the gradient between the core and its surroundings, which stabilizes the presence of heavier material above the core. Any cooler and convection isn't strong enough, and heavier material settles back into the core.

Because most planets are thought to have been built by multiple collisions among protoplanets and smaller bodies, the authors think it's worth exploring whether diffuse cores could be a common feature of gas giants. There have been a number of giant exoplanets that appear to have high metal content in their atmospheres, which might be the product of similar events.

There's no obvious way to test these things at the moment, and there's still a chance that further data from Juno will suggest alternate explanations. But if the idea holds up, planetary scientists will undoubtedly start considering the implications of these collisions and might come up with some overt indication of the marks they leave on gas giants.

Quelle: arsTechnica

----

Update: 18.09.2019

.

NASA's Juno Mission Checks Out Eclipse on Jupiter

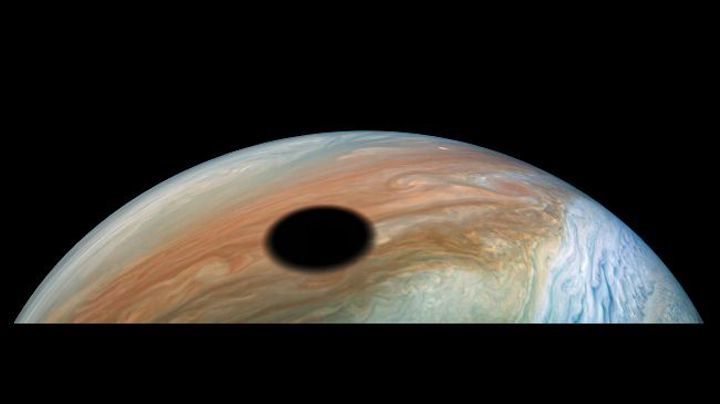

All is well on our largest neighbor; NASA's Juno spacecraft just managed to spot the shadow of Jupiter's moon, Io, passing over its marbled clouds.

The Juno mission made its 22nd close skim over the gas giant around Sept. 11, when the celestial geometry was just right for Io to slip between the sun and the planet during one of its rapid-fire circuits of Jupiter. (The moon takes just 1.77 days to orbit the planet.)

Io is the most volcanic world in our solar system, thanks to heat generated by the close tug of Jupiter's massive gravity. Of Jupiter's four large moons, Io orbits closest to the planet, allowing it to cast a vast shadow on the gas giant.

NASA's Juno spacecraft has been orbiting Jupiter for more than three years, making a close approach every 53 days. Scientifically, the spacecraft's priorities are a host of instruments that are designed to study the planet's atmosphere and interior.

But also onboard Juno is a camera; All of the raw images that camera captures are uploaded online, where volunteer image processors get to work turning the raw files into something beautiful, informative, or both.

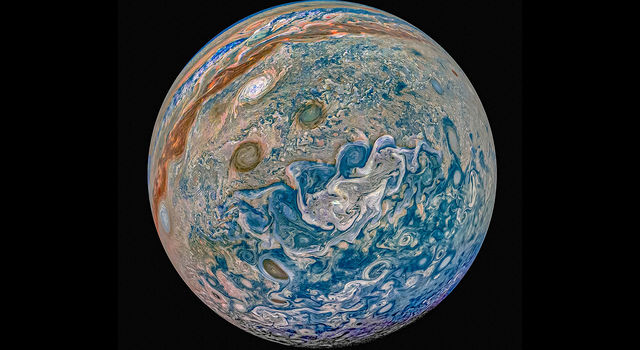

That means that while we wait for scientists to analyze the rest of Juno's data, we can enjoy stunning images of Jupiter, like these eclipse shots. The images mimic photographs taken from space of eclipses here on Earth, when the moon's shadow crosses the planet.

Quelle: SC

----

Update: 3.10.2019

.

NASA's Juno Prepares to Jump Jupiter's Shadow

This animated gif depicts the point of view of NASA's Juno spacecraft during its eclipse-free approach to the gas giant Nov. 3, 2019. The Sun is depicted as the yellow dot rising up just to left of the planet. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SWRI

Last night, NASA's Juno mission to Jupiter successfully executed a 10.5-hour propulsive maneuver - extraordinarily long by mission standards. The goal of the burn, as it's known, will keep the solar-powered spacecraft out of what would have been a mission-ending shadow cast by Jupiter on the spacecraft during its next close flyby of the planet on Nov. 3, 2019.

Juno began the maneuver yesterday, on Sept. 30, at 7:46 p.m. EDT (4:46 p.m. PDT) and completed it early on Oct. 1. Using the spacecraft's reaction-control thrusters, the propulsive maneuver lasted five times longer than any previous use of that system. It changed Juno's orbital velocity by 126 mph (203 kph) and consumed about 160 pounds (73 kilograms) of fuel. Without this maneuver, Juno would have spent 12 hours in transit across Jupiter's shadow - more than enough time to drain the spacecraft's batteries. Without power, and with spacecraft temperatures plummeting, Juno would likely succumb to the cold and be unable to awaken upon exit.

"With the success of this burn, we are on track to jump the shadow on Nov. 3," said Scott Bolton, Juno principal investigator at the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. "Jumping over the shadow was an amazingly creative solution to what seemed like a fatal geometry. Eclipses are generally not friends of solar-powered spacecraft. Now instead of worrying about freezing to death, I am looking forward to the next science discovery that Jupiter has in store for Juno."

Juno has been navigating in deep space since 2011. It entered an initial 53-day orbit around Jupiter on July 4, 2016. Originally, the mission planned to reduce the size of its orbit a few months later to decrease the period between science flybys of the gas giant to every 14 days. But the project team recommended to NASA to forgo the main engine burn due to concerns about the spacecraft's fuel delivery system. Juno's 53-day orbit provides all the science as originally planned; it just takes longer to do so. The spacecraft's longer life at Jupiter is what led to the need to avoid the gas giant's shadow.

"Pre-launch mission planning did not anticipate a lengthy eclipse that would plunge our solar-powered spacecraft into darkness," said Ed Hirst, Juno project manager at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. "That we could plan and execute the necessary maneuver while operating in Jupiter's orbit is a testament to the ingenuity and skill of our team, along with the extraordinary capability and versatility of our spacecraft."

NASA's JPL manages the Juno mission for the principal investigator, Scott Bolton, of the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. Juno is part of NASA's New Frontiers Program, which is managed by NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, for the agency's Science Mission Directorate. The Italian Space Agency (ASI) contributed two instruments, a Ka-band frequency translator (KaT) and the Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper (JIRAM). Lockheed Martin Space in Denver built and operates the spacecraft.

Quelle: NASA

----

Update: 13.12.2019

.

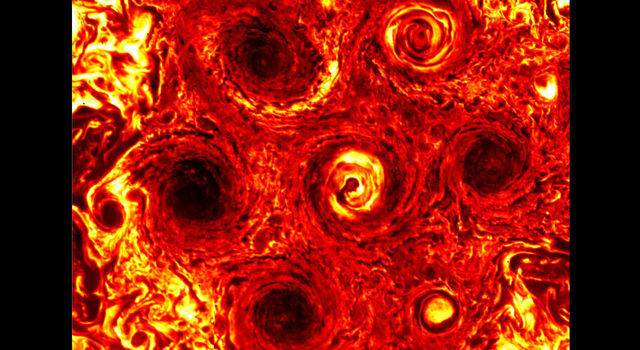

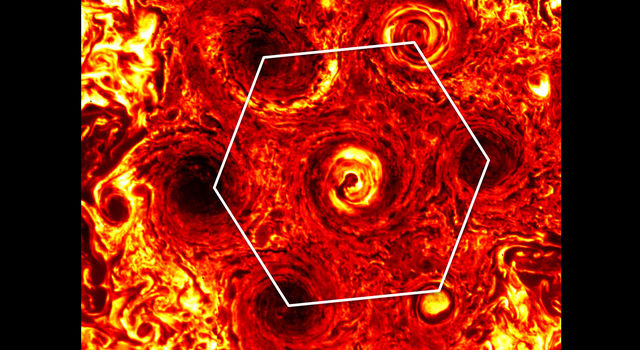

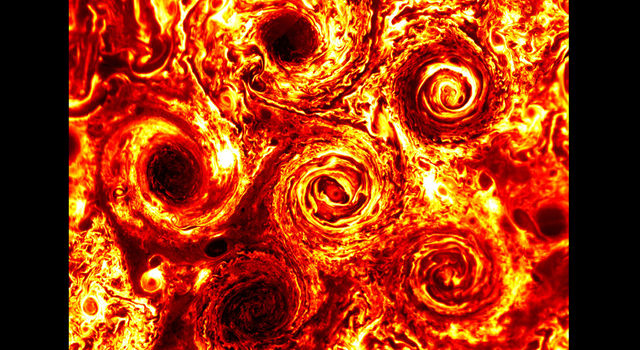

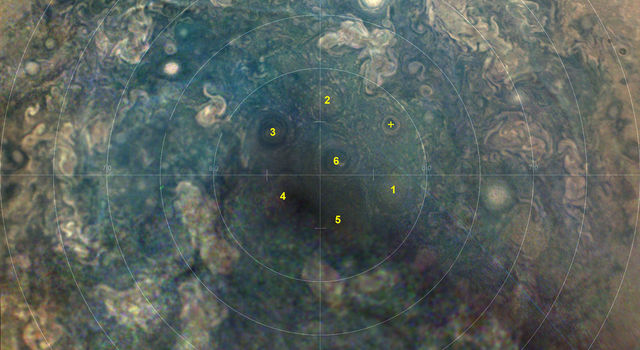

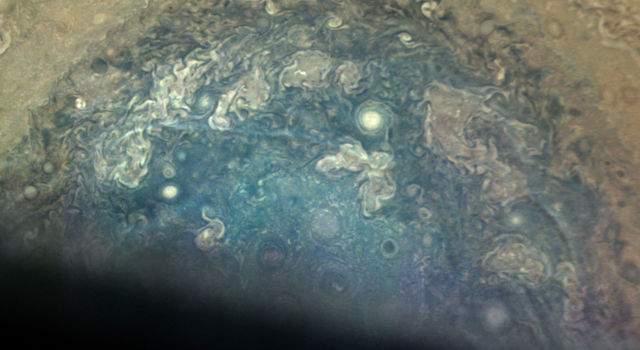

NASA's Juno Navigators Enable Jupiter Cyclone Discovery