18.07.2019

Apollo taught us that landing on the Moon is a dusty nightmare

Landing people on the Moon is messy — a lesson that the Apollo astronauts learned the hard way. Using a rocket engine to lower a large spacecraft down to the lunar surface kicks up a whole lot of fast-moving dust that can travel far and wide, capable of hitting and even damaging spacecraft on and around the Moon. It’s an issue that some engineers say we need to address now, especially if we want to land more people on the Moon within the next decade.

Space explorers have the Moon’s unique environment to thank for this dusty aftereffect. Our lunar neighbor is about one-quarter the size of Earth, and it has one-sixth the gravity of our planet. It also lacks an atmosphere, making it easy for tiny objects to sail over the surface for some time before coming back down. So if you aim a rocket engine at the Moon for an extended period of time — which you typically need to do to lower something down to the surface — it can easily accelerate lunar dirt to speeds of thousands of meters per second, sending them hundreds of miles away.

The handful of Apollo landings conducted in the 1960s and ‘70s weren’t powerful or frequent enough to cause panic about this kicked-up dust. But now NASA wants to go back to the Moon, this time to stay. Maintaining an extended human presence on the lunar surface is going to require a lot of landings — to transport people, cargo, habitats, and more to the Moon. Without any major infrastructure changes, that’s going to increase the possibility of kicking up dust that could damage spacecraft around the Moon, the historical Apollo sites, or even the Moon base that NASA wants to build and maintain. It could also lead to tensions between nations that have spacecraft near each other.

“There’s potential for serious international conflict because of this,” says Phil Metzger, a planetary physicist at the University of Central Florida who used to work at NASA studying the effects of rocket blasts on planetary bodies.

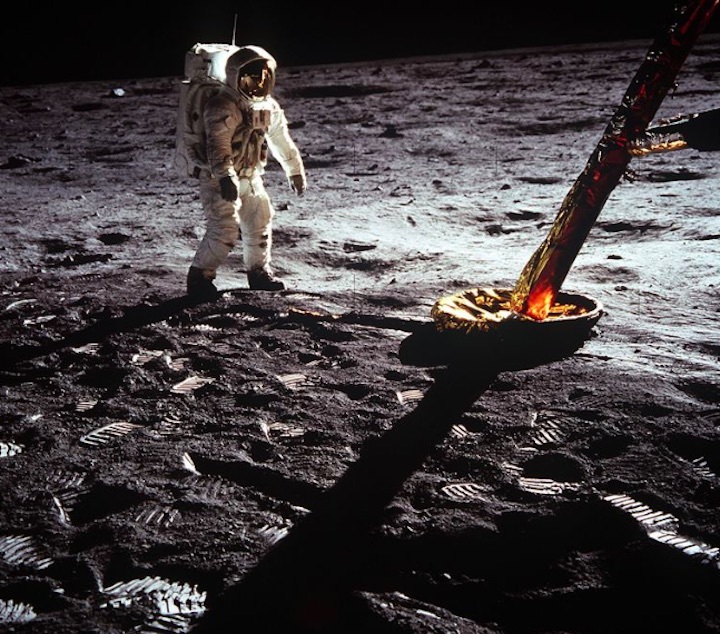

Lunar dust turned out to be a bit of a nightmare for the Apollo astronauts. For one thing, it clung to everything. The astronauts got dust all over their suits, which degraded the material over time. The particles even mucked up a lot of the equipment the astronauts were using, including cameras, radiators, buttons, and more. And the dust blown out during the descent to the lunar surface made it difficult for the astronauts to see where they were going. “I think probably one of the most aggravating, restricting facets of lunar surface exploration is the dust and its adherence to everything no matter what kind of material, whether it be skin, suit material, metal, no matter what it be,” Apollo 17 astronaut Gene Cernan said during a debrief after the mission in 1973. Dealing with this grime will be a big hassle for future lunar exploration missions — especially if we want to put habitats up there.

Even before people step out the door of a lunar lander, the dust will be a problem, starting from the second the landing engine turns on. Here on Earth, if you pointed a rocket engine at a bunch of dust, gravel, and rocks, the thick atmosphere of air that surrounds our planet would slow down the smaller particles first, while the larger particles would cut through the wind resistance and travel the greatest distances. On the Moon, it’s the opposite. There is no air surrounding the lunar surface, just vacuum. So if a bunch of particles were to get sped up to high speeds, the smaller particles would travel the fastest and at the greatest distances, while the bigger rocks would soon be felled by the Moon’s weak gravity.

That’s exactly what happens when you use a rocket engine to lower down to the lunar surface. Thanks to what we’ve learned from the Apollo missions, engineers have found that a large lander about the size of the Apollo Lunar Module — capable of spewing out gas at around 2,400 meters per second — can propel rocks and gravel-sized particles up to 10 to 100 meters per second, sending them tremendous distances (up to six football fields away). But the fine dust and sand can speed up to 1,000 meters per second, propelling them hundreds of kilometers away — or even distributing them all over the Moon.

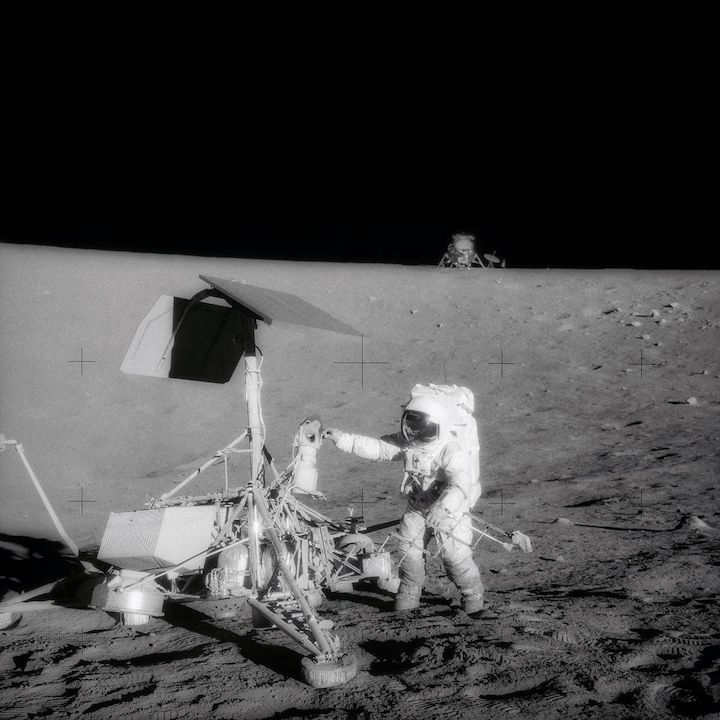

Any machinery in the path of these high-speed particles could suffer some serious blasting or damage. “It could ruin a spacecraft in orbit around the Moon if it just happens to be in the wrong place at the wrong time,” says Metzger. The Apollo 12 astronauts saw this effect when they touched down on the Moon in November of 1969. They deliberately landed near a robotic probe called Surveyor 3 that NASA had landed on the Moon in 1967. When they took pieces of the probe back to Earth with them, researchers found that Surveyor 3 had been thoroughly sandblasted by dust from the landing.

“We can see the lunar soil particles penetrated deep into the surface all over the Surveyor,” says Metzger, who led a team that studied parts of the Surveyor 3 probe that returned from Apollo 12. “We can see the paint all cracked up.”

The problem may grow even worse as NASA looks to send humans back to the Moon, since some of the landers that have been proposed by private companies like Blue Origin, Lockheed Martin, and SpaceX would be much bigger than the Apollo landers. The result of all these landers touching down on the Moon: even more dust and large particles blown out at faster speeds.

“It’ll be even worse,” says Metzger. “It will be sand-sized stuff blown completely off the Moon into orbit around the Sun. Larger particles like gravel will be dispersed longer distances.” Logistically, that could be bad news for any future habitats that NASA or other space agencies might want to build on the Moon. “If you land too close to your outpost, it could be like pelting your outpost with gravel traveling like the speed of bullets,” says Metzger.

It’s also an issue for historical preservation. Space archeologists are interested in keeping the Apollo landing sites as pristine as possible, to potentially study them in the future. “There’s still a lot to be learned archaeologically from these early sites,” Beth O’Leary, a space archeologist at New Mexico State University, tells The Verge. For instance, O’Leary is interested in potentially comparing the technology of the early Soviet robotic spacecraft that landed on the Moon to the early American-made spacecraft, but that can only be done if the parts remain the same as they were when they landed in the 1960s.

“You could only do that by looking at the artifacts of the site in [its original place],” says O’Leary. “Because when you take something away, you can record it, you can preserve it in a museum, but you take away the integrity of the site.”

Additionally, O’Leary isn’t just concerned about hardware artifacts, but also the features that the Apollo astronauts left behind in the soil — notably their lunar footprints. “Anything that’s a feature on the Moon really risks being disturbed by wind, by any kind of erosive forces,” O’Leary says. “And the way in which spacecraft in the future could land, or where they would land would essentially obliterate those.”

One way to preserve all of these vehicles and machinery is to land far enough away so that valuable hardware remains intact. But researchers don’t know the best minimum distance. In 2011, Metzger and a team of researchers attempted to come up with guidelines for how far away from the Apollo sites other entities should land, in order to cause as minimal damage as possible. The team settled on a distance of 2 kilometers away, but Metzger says the number is arbitrary — there really is no minimum safe distance. Since landers have the potential to disperse dust globally, it all depends on how much damage is considered “okay.” Lunar robots can handle some amount of bombardment — in fact, interplanetary dust is falling on the Moon all the time — but it’s unclear when damage becomes a liability.

“At some distance, the amount of damage you’re going to cause would be negligible compared to what nature is doing,” says Metzger. “But we aren’t smart enough to figure out what that distance is.”

To alleviate the risk of damage, Metzger says NASA and other commercial companies headed to the Moon need to seriously consider making landing pads on the lunar surface before landings become routine. But there are pitfalls to that solution, too. Bringing up a prefabricated metal landing pad to install on the surface would require huge amounts of fuel and vast sums of money. Another option is to use microwaves or other heated tools to melt the lunar soil into a flat surface, but that requires the use of experimental tech.

In the end, any landing pad option is going to require new sophisticated technologies, and may make lunar missions more complex and expensive. Given the already high costs of lunar return missions, it’s very possible NASA and other commercial companies may skip this step. That’s why Metzger argues it’s time for countries come to some kind of agreement that damage to their lunar spacecraft will be a very real possibility.

In addition to the United States’ Apollo sites, China and Russia both sent robots to the Moon, and other countries, including India and Japan, have crashed spacecraft into the lunar surface. These vehicles, or their remains, may be in the line of fire no matter where a large human lander plops down. “I think we need to have an international agreement that we are all agreed together that we’re going to be allowed to sandblast each other’s hardware,” says Metzger. “If we can’t agree on that, then that means you just can’t land certain places on the Moon. And that means countries are going to be able to claim effective territory.”

The US is still many years away before humans will be traveling to and from the Moon with regularity, so there’s still plenty of time to think about this before international tensions arise. But if NASA and the private space industry are truly serious about going to the Moon to stay, these organizations will need to get very familiar with the particles that blanket the lunar surface. Because their vehicles will be spraying lunar dust all over the Moon, whether they want to or not.