8.06.2019

ROCKETS, EVAPORATING DROPLETS AND X-RAYING METALS

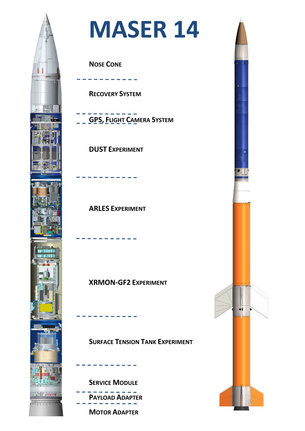

Years of preparation, and the finale is over in six minutes. This month a sounding rocket will launch two ESA experiments to an altitude of 260 km to provide six minutes of weightlessness as they free-fall back to Earth.

Rockets carrying satellites into orbit are typically launched from sites around the equator, such as Europe’s Spaceport in Kourou, French Guiana. There are alternatives for experiments in microgravity and ESA runs Maser campaigns from the Esrange Space Center in Sweden, shooting 400 kg worth of scientific equipment into the sky.

This year’s campaign will host investigations looking at the finer details of metal casting and how fluids evaporate.

Evaporating nano-liquids

Temperature control is a constant preoccupation for engineers on Earth, but even more so in space where the extreme environment requires innovative solutions to keep equipment and astronauts at the right temperature.

The ARLES experiment (Advanced Research on Liquid Evaporation in Space) investigates how liquids evaporate in microgravity. The research focuses on understanding how liquids can best be used to transfer heat and could help improve thermal control systems in space.

The experiment will repeatedly evaporate droplets of less than 10 microliters in microgravity under different conditions – including adding an electric field to the mix – to see how they behave. Infrared video and interferometers record the process for researchers around the world to analyse.

One liquid will include graphene nanoparticles, a material which is of particular interest among the scientific community. The experiment will also increase understanding of how nanoparticles in the fluid coats surfaces as the fluid evaporates.

Daniele Mangini, ESA’s science coordinator for the experiment says, “This technique could be a novel way of creating smart coatings, membranes and sensors and even create complex nano-structures. Nano-particles are difficult to test in the closed environment on the International Space Station, so a sounding rocket campaign is ideal for this experiment.

“Weightlessness is necessary for this analysis. On Earth, gravity causes the deposits to spread unevenly, which is often detrimental for applications. It is more difficult to investigate the underlying phenomena because many effects, such as sedimentation, thermo-capillarity and natural convection make it hard to focus on what we are interested in researching.

“The six exciting minutes in microgravity will allow the scientific team to disentangle the processes, helping to understand characteristic signatures during nano-particle deposition and self-assembly.”

Growing metal crystals

In the second ESA experiment, particles will also be added to a molten metal alloy to improve the resulting properties. The XRMON experiment is a recurrent flyer on sounding rockets and is investigating how metal alloys form, searching to improve the materials we use in our everyday life.

On this 14th Maser campaign a 0.2-mm-thin piece of aluminium-copper alloy will be melted and then solidified in weightlessness. An x-ray beam will illuminate the metal sample and a camera will record it, similar to a medical radiography.

“We teach how metals solidify to students in university, and this really allows us to see it happening, in weightlessness” says ESA’s science coordinator for this experiment Wim Sillekens.

Researchers are interested in how microstructures form as the metal solidifies.

“On Earth, the crystals in this alloy will rise in the liquid as they form – somewhat like how water ice crystals become ice cubes and will rise to the top of your drink,” continues Wim, “in weightlessness there is no buoyancy – in space an ice cube would stay suspended in your drink – allowing us to investigate the crystal-forming process more easily.”

The XRMON experiment ran on the Maser 12 campaign in 2012, and then on the Maser 13 campaign in 2015, but with different parameters allowing researchers to compare data and the cast alloy to further improve techniques.

Down to Earth

It only takes the Maser rocket 45 seconds to leave the atmosphere and it lands back on Earth in less than 15 minutes. Parachutes deploy to lessen the impact of touchdown to 30 km/h in the wilderness of Sweden.

Antonio Verga, ESA’s head of non-Space Station payloads and platforms, says “Helicopters will return the experiments to Esrange and the whole process will be completed in two hours, but the unique results typically give many years of data to process and analyse!”

The flights are part of ESA’s SciSpace programme that allows researchers to run experiments in altered gravity – from hypergravity to the International Space Station – to investigate our Universe and improve the technology we use in space and in everyday life. Another sounding rocket campaign will be held in October this year.

Another platform for microgravity experimentation is the Space Rider laboratory. To be launched on a Vega-C rocket, the high-tech space lab can fit up to 800 kg of payloads inside the environmentally controlled cargo bay that will run in low-Earth orbit for a minimum of two months before returning its payloads to Earth.

Like sounding rockets, Space Rider will enable a range of experiments in microgravity and open opportunities for educational missions, starting in 2022.

Rockets are the backbone of all space-based endeavours. ESA in partnership with industry is developing next-generation space transportation vehicles, Ariane 6, Vega-C, and Space Rider. At Space19+, ESA will propose further enhancements to these programmes and introduce new ideas to help Europe work together to build a robust space transportation economy. This week, take a look at what ESA is doing to ensure continued autonomous access to space for Europe and join the conversation online by following the hashtag #RocketWeek

Quelle: ESA