31.03.2019

An oxygen tank exploded in the supply module of Apollo 13. The astronauts aboard the command module lost their air feed, electricity, water and heat.

They were 200,000 miles from Earth.

Air Force Capt. Jon Rockstad, the senior search and rescue controller stationed at the Ramstein Air Base in Germany, stood stunned in the command center.

“What can we do?” Rockstad, of Summerville, remembered thinking.

“They’re out there and if they don’t come back there’s no game plan,” he said in a recent interview. “Search and rescue only comes into play once they get back in the world.”

The golden achievement of American space travel — the first moon landing — took place 50 years ago this summer in 1969. But that successful landing was part of a larger drama NASA and the space program faced during an 16-month period that Rockstad considers a peak of his career.

It started with the Apollo 8 “Earthrise” lunar orbit and culminated with the frightening, near disastrous turn of events aboard Apollo 13 the next April where Rockstad watched helplessly.

Amid it all, countless support people like Rockstad were there, standing duty around the world to help pull it off.

‘Make it fancy’

The Apollo program was an enormous yet almost thrown-together human endeavor. Four flights were launched in the year the U.S. landed on the moon and six within a year and a half of that landing.

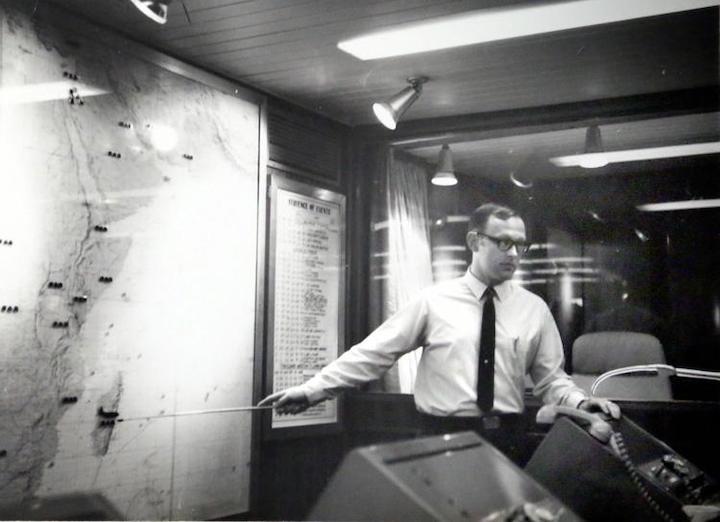

A photo of Col. Jon Rockstad (retired), who now lives in Summerville during his time as Senior Rescue Controller for both the Apollo 11 moon landing and the Apollo 13 abort and recovery mission. Brad Nettles/Staff

All together, 11 missions were crewed by humans in only three years. The entirety of the 17-flight Apollo program took place over four years. The cost was $170 billion in today’s money.

For Rockstad, the early Apollo 11 landing was an ecstatic moment. The command center staff erupted in cheers, four-star generals high-fived each other in the plush viewing box behind the glass. Eight months later, they stood in shock.

Rockstad had already had an astounding career.

He flew C-130 transport aircraft in Vietnam and dealt with an engine fire while resupplying the McMurdo Station in Antarctica, among other challenges, before moving to search and rescue command.

He would go on to command missions such as the hunt for a stolen C-130 with an AWOL airman at the controls. He retired as a colonel.

The Apollo command remains unparalleled for him.

Rockstad, now 80, has the gregarious, rallying nature of a commander and a voice tinged with awe when he talks about the missions.

The Ramstein search-and-rescue control center was one of a handful positioned around the world, dedicated to keep watch and respond to errant spashdowns if needed. Rockstad’s responsibility was to oversee any rescue that might have to take place from Europe and Africa to India.

The Apollo program was so urgent and the details kept so secret, he didn’t know what his assignment would be until he arrived at Ramstein in 1968. Once he got there, because he had design experience and had seen a rescue control center in the United States, the colonel told him to build one at Ramstein. Immediately.

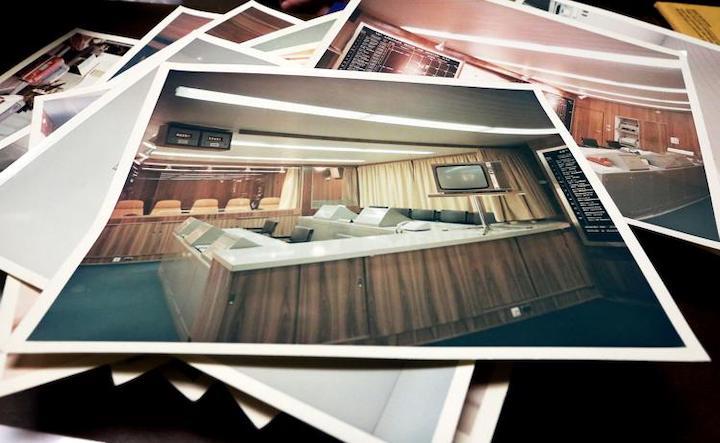

“Make it fancy,” the colonel ordered, because both knew the “stars,” or generals would be there for the flights. The control room Rockstad put together looked like a living room except for the big screens and boxlike computer terminals. The VIP room behind the glass was like a sports arena luxury box.

Photos of the control room Col. Jon Rockstad (retired), designed in Germany during his time as Senior Rescue Controller for both the Apollo 11 moon landing and the Apollo 13 abort and recovery mission. Brad Nettles/Staff

“You talk about plush,” Rockstad said with a grin.

The first moon landing flight went so smoothly that the rescue control crew had little to do but monitor. Apollo 13 would be anything but smooth.

‘An eternity’

“Houston, we have a problem,” astronaut Jack Swigert radioed NASA in what would become a timeless catch phrase.

The Apollo 13 crew was forced to move from the powerless command module to the spacecraft’s lunar exploration module to survive. They had to fend their way back to Earth with compromised equipment and improvised plans.

Then they had to climb back in the ice-cold shell of the command module to try to land it — somewhere.

For two long hours, Rockstad was in charge of the people who expected to be called on to rescue the Apollo 13 crew.

Even if the Apollo crew could survive reentry in the damaged command module, its trajectory would be sped up. Nobody could be sure when or where the craft would splash down.

The remote Indian Ocean was in the hemisphere the craft would cross to reach the planned Pacific touchdown. That made the ocean one of the likelier possibilities.

NASA told Rockstad to get a plane ready. The Ramstein staff looked around with “Are you kidding me?” expressions.

No Navy ships were in the Indian Ocean. No C-130 plane and crew had been pre-positioned for Apollo 13 on Mauritius Island off Africa in the west of the ocean, as a cost-cutting move after the relatively flawless earlier moon missions. The nearest plane and crew were in the Azores — 6,000 miles away.

Rockstad ordered the Azores crew into action, knowing they wouldn’t make even Mauritius for two days. Then a thunderstorm struck at Ramstein, knocking out power except for an emergency generator and reducing communications to the single “hot line” telephone on a landline.

The room got tense and hot. Fifty years later, thinking back on those hours, his eyes still get a little lost. His hands get restless.

“We didn’t know where they were going to land, if they lived to get there,” he said. “It was an eternity.”

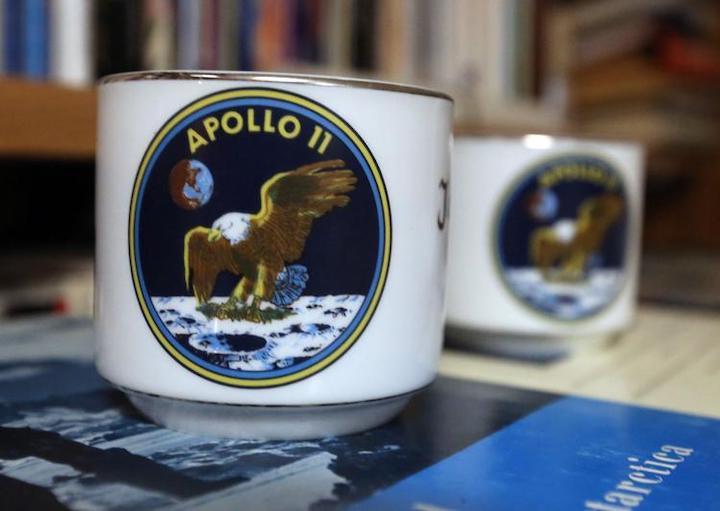

Col. Jon Rockstad (retired), received coffee mugs for his work as Senior Rescue Controller for both the Apollo 11 moon landing and the Apollo 13 abort and recovery mission. Brad Nettles/Staff

As it turned out, the improvised engineering and planning went so well the Apollo crew needed only a minor throttle correction to get the craft back on track. It landed where it was supposed to, off Samoa in the Pacific. Rockstad heard later that the touchdown was so precise, one of the waiting ships had to move out of the way.

After the Apollo 11 moon landing, he had been given a coffee mug with a bald eagle and Apollo 11 insignia for his work. His toddler children would recall later that he drank from it every day before reporting to duty at Ramstein.

He had the mug in the rescue command center for the Apollo 13 flight. He drinks coffee from it today.

“In hindsight, it was history,” Rockstad said. “I lived it in real time.”

Rockstad’s reflections comes as commemorations have already started and will peak toward the historic July 20 anniversary of “the Eagle has landed” flight — the successful 1969 moon landing.

The remembrance is particularly notable with NASA officials now planning to return to the moon.

Quelle: The Post and Courier