25.03.2019

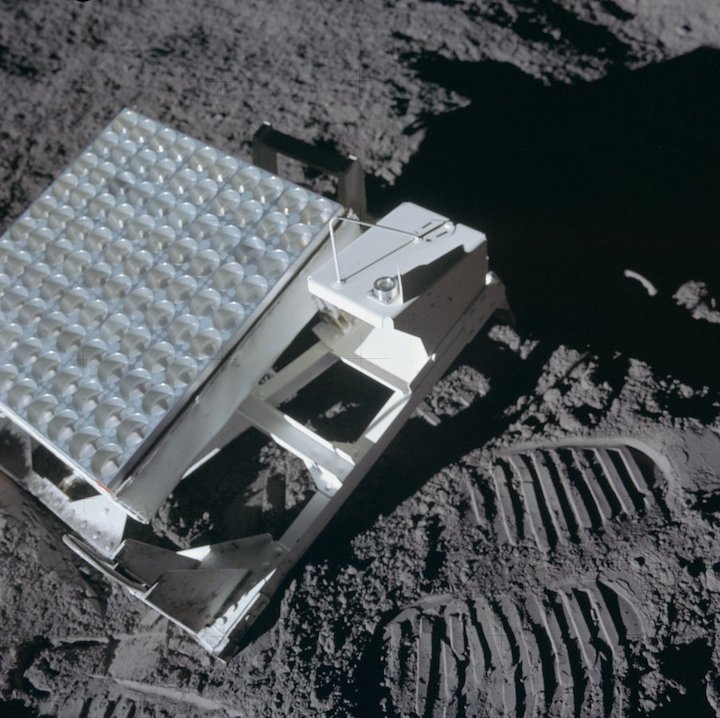

The Apollo 14 mission's retroreflector, as seen in place on the moon's surface

THE WOODLANDS, Texas — NASA science instruments are flying to the moon aboard two international lunar missions, according to agency officials.

The Israeli lander Beresheet, due to touch down April 11, and the Indian mission Chandrayaan 2, scheduled to launch next month, are each carrying NASA-owned laser retroreflector arrays that allow scientists to make precise measurements of the distance to the moon. NASA confirmed the two instruments during the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference held here.

"We're trying to populate the entire surface with as many laser reflector arrays as we can possibly get there," Lori Glaze, acting director of the Planetary Science Division of NASA's Science Mission Directorate, said during a town hall event on March 18 during which she announced the Chandrayaan 2 partnership.

Glaze did not provide a timeline for the partnership's creation, but for the Beresheet mission at least, NASA's involvement came with quite little warning as the agency scrambled to find a way to participate.

"We were asked rather quickly if there was anything we wanted to contribute to that lander, and we were successful in roughly a two-week time period to come up with an agreement on it," Steve Clarke, the deputy associate administrator for exploration within the Science Mission Directorate, said during the same event. "We were able to put a laser retroreflector assembly on the Beresheet, so that is flying with the lander and we're looking forward to a successful landing."

Glaze and Clarke did not provide additional details about the instruments onboard or the process of getting them there, but these reflectors won't be the first the agency has placed on the moon. In fact, retroreflector experiments are some of the continuing science gains of the Apollo program, which placed three such contraptions on the moon's surface. The Soviet Union's Luna programadded another two such instruments.

Retroreflectors are essentially sophisticated mirrors. Scientists on Earth can shoot them with lasers and study the light that is reflected back. That signal can help pinpoint precisely where the lander is, which scientists can use to calculate its — and the moon's — distance from Earth.

And while five such instruments already exist on the lunar surface, they have some flaws. "The existing reflectors are big ones," Simone Dell'Agnello, a physicist at the National Institute for Nuclear Physics National Laboratory at Frascati, Italy, told Space.com. Dell'Agnello was recently part of a team that designed a new generation of lunar retroreflectors that should allow for more-precise measurements.

They are large arrays of individual reflectors, which means it takes thousands of laser pulses to sketch out the shape of the whole array and its position. Dell'Agnello said he would rather see individual reflectors instead of arrays, as smaller units would waste fewer laser pulses and allow more-precise measurements of the moon's surface. Those analyses could become so detailed that scientists could see the daily rise and fall of any lander surface the device is resting on as that surface expands and contracts with the moon's dramatic temperature changes.

The retroreflectors flying on Beresheet and Chandrayaan 2 are smaller than the Apollo ones, Dell'Agnello said. And NASA isn't just aiming to install more of these instruments; the agency also wants to build new laser stations here on Earth to signal to the reflectors, Glaze mentioned during her remarks.

Quelle: SC