9.03.2019

The four Magnetospheric Multiscale spacecraft are flying out of their element. The spacecraft have just completed a short detour from their routine science — looking at processes within Earth’s magnetic environment — and instead ventured outside it, studying something they were not originally designed for.

For three weeks, MMS studied the solar wind — the stream of supersonic charged particles flung around the solar system by the Sun — to better understand what’s known as turbulence in plasmas, the heated, electrified gases that make up 99 percent of ordinary matter in the universe. Turbulence is the chaotic motion of a fluid. It shows up in daily life everywhere from eddies in a river to smoke from a chimney, but it is incredibly hard to study because it’s so unpredictable and it remains one of the least well understood disciplines in all of physics. The mini-campaign will provide scientists with an up close and in-situ view to push the frontiers of the field.

But to take these groundbreaking measurements, MMS had to operate in an entirely new way — and MMS scientists and engineers designed a clever way to allow the spacecraft to study the solar wind with unprecedented accuracy, testing the limits and versatilities of MMS’ capabilities.

Opening New Doors

The Magnetospheric Multiscale mission, MMS, was launched in 2015 to study magnetic reconnection — the explosive snapping and forging of magnetic field lines, which flings high-energy particles around Earth. MMS was built with state-of-the-art instruments that take measurements with nearly 100 times better resolution than previous instruments. After two years of studying magnetic reconnection in Earth’s magnetic environment — the magnetosphere — on the dayside, MMS elongated its orbit to begin looking at reconnection behind Earth, away from the Sun, where it’s thought to spark the auroras.

Since MMS has completed its original mission goals, it’s now taking time in its extended mission to tackle some new science objectives. Understanding turbulence, which is one of NASA’s prime science objectives, is the first mini-campaign MMS plans to undertake.

“We would like to make a lot of these mini-campaigns in the future if this one is successful, which it’s already shaping up to be,” said Bob Ergun, researcher at the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics in Boulder, Colorado, who heads the new campaign. “MMS is a very, very powerful observatory with incredibly sensitive instruments on it and we’re trying to maximize their use to study these other priority sciences.”

Thinking Outside of the Magnetosphere

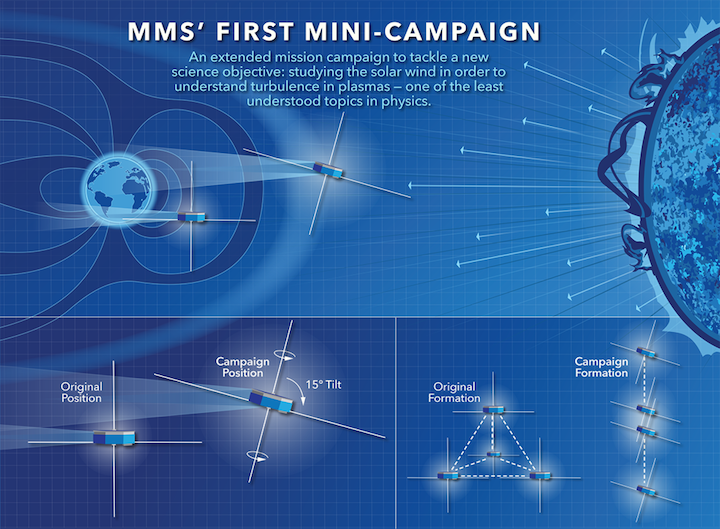

Studying the solar wind is best done from in the solar wind, but most of the time, the four MMS spacecraft orbit within or on the edge of Earth’s magnetosphere — where the magnetic field creates a buffer that protects the spacecraft from the solar wind. Occasionally, however, routine orbital adjustments, used to maintain MMS’ elongated orbit, take it well outside. This year, a boost to the spacecraft orbit is taking MMS entirely out of Earth’s magnetic environment and past the bow shock — a region where the supersonic solar wind slams into Earth’s magnetosphere. At such a distance, MMS passes through the solar wind itself, which allows a window of time to study the region’s turbulence.

Studying the solar wind is nothing like studying magnetic reconnection, but can be done with the same instruments that measure magnetic and electric fields. MMS is equipped with some of the most precise instruments ever flown in space, but in order to use them to study the solar wind, some adjustments first need to be made.

Normally MMS flies in a pyramid-shaped formation called a tetrahedron, which allows all four spacecraft to be equally separated. As they flew through the solar wind, the spacecraft were instead arranged in what scientists call a “string of pearls.” Flying perpendicular to the wind, the spacecraft followed one after another, each offset at distances of 25 to 100 kilometers (about 15.5 to 62 miles) from their neighbor. This allows scientists to see how much the solar wind varies over different distances.

However, as the spacecraft travel through the supersonic solar wind they create a wake behind them, just like a boat. This wake is not a natural feature in the solar wind, so the MMS scientists want to avoid having their instruments, which spin at the end of long booms, dragged through it. To make precise measurements unencumbered by the wake, the spacecraft were each tilted up 15 degrees. The tilt lifts the spinning booms up from travelling behind the spacecraft through the wake.

This angle allows scientists to get better data, but it comes with a cost. As a result of the tilt, the solar array doesn’t get as much light, meaning the spacecraft’s power is reduced by a few watts each. The tilt also puts thermal stress on the spacecraft, since the top of each gets hotter than the bottom. For a short campaign however, these effects won’t permanently affect the spacecraft.

Old Spacecraft, New Tricks

The data MMS gathered in this campaign will be some of the most accurate measurements of turbulence in the solar wind ever made. The research will also complement the work being done by NASA’s Parker Solar Probe, which flies through the Sun’s atmosphere studying the origins of the solar wind. While Parker Solar Probe measures the initial turbulence in the solar wind, MMS measured the aftermath when it reaches Earth.

“Almost all of the astrophysical plasmas we look at around the Sun, stars, black holes, accretion disks, jets, are all extremely turbulent, so by understanding it around Earth we understand it elsewhere,” Ergun said.

Ultimately this mini-campaign will also serve as a test case for what MMS is capable of doing in the future. Learning the nuances of MMS’ formations and tilt angles will allow the scientists to better understand MMS’s range of abilities, which may open the door up for other types of scientific campaigns as well.

Quelle: NASA

----

Update: 10.08.2019

.

NASA’s MMS Finds First Interplanetary Shock

The Magnetospheric Multiscale mission — MMS — has spent the past four years using high-resolution instruments to see what no other spacecraft can. Recently, MMS made the first high-resolution measurements of an interplanetary shock.

These shocks, made of particles and electromagnetic waves, are launched by the Sun. They provide ideal test beds for learning about larger universal phenomena, but measuring interplanetary shocks requires being at the right place at the right time. Here is how the MMS spacecraft were able to do just that.

What’s in a Shock?

Interplanetary shocks are a type of collisionless shock — ones where particles transfer energy through electromagnetic fields instead of directly bouncing into one another. These collisionless shocks are a phenomenon found throughout the universe, including in supernovae, black holes and distant stars. MMS studies collisionless shocks around Earth to gain a greater understanding of shocks across the universe.

Interplanetary shocks start at the Sun, which continually releases streams of charged particles called the solar wind.

The solar wind typically comes in two types — slow and fast. When a fast stream of solar wind overtakes a slower stream, it creates a shock wave, just like a boat moving through a river creates a wave. The wave then spreads out across the solar system. On Jan. 8, 2018, MMS was in just the right spot to see one interplanetary shock as it rolled by.

Catching the Shock

MMS was able to measure the shock thanks to its unprecedentedly fast and high-resolution instruments. One of the instruments aboard MMS is the Fast Plasma Investigation. This suite of instruments can measure ions and electrons around the spacecraft at up to 6 times per second. Since the speeding shock waves can pass the spacecraft in just half a second, this high-speed sampling is essential to catching the shock.

Looking at the data from Jan. 8, the scientists noticed a clump of ions from the solar wind. Shortly after, they saw a second clump of ions, created by ions already in the area that had bounced off the shock as it passed by. Analyzing this second population, the scientists found evidence to support a theory of energy transfer first posed in the 1980s.

MMS consists of four identical spacecraft, which fly in a tight formation that allows for the 3D mapping of space. Since the four MMS spacecraft were separated by only 12 miles at the time of the shock (not hundreds of kilometers as previous spacecraft had been), the scientists could also see small-scale irregular patterns in the shock. The event and results were recently published in the Journal of Geophysical Research.

Going Back for More

Due to timing of the orbit and instruments, MMS is only in place to see interplanetary shocks about once a week, but the scientists are confident that they’ll find more. Particularly now, after seeing a strong interplanetary shock, MMS scientists are hoping to be able to spot weaker ones that are much rarer and less well understood. Finding a weaker event could help open up a new regime of shock physics.

Quelle: NASA