7.03.2019

NASA to replace Europa Clipper instrument

WASHINGTON — NASA has removed an instrument previously selected for the Europa Clipper mission, citing cost growth, but will seek ways to replace it with a less complex design.

In a March 5 statement, NASA said that it would no longer pursue development of the Interior Characterization of Europa Using Magnetometry (ICEMAG) instrument, a magnetometer designed to measure the magnetic field around the icy moon of Jupiter. ICEMAG was one of nine instruments originally selected by NASA in 2015 for development for the Europa Clipper mission.

NASA said that the increasing cost of ICEMAG, still in its preliminary design phase, led to its removal from the mission. “I believe this decision was necessary as a result of continued, significant cost growth and remaining high cost risk for this investigation,” Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA associate administrator for science, said in a memo.

In that memo, he said that ICEMAG exceeded a “cost trigger” last summer that had been put in place for it and other instruments to keep costs under control. That cost trigger escalated reviews of the instrument all the way to NASA Headquarters, including a briefing there Feb. 14. The key problem with the instrument was accommodating its “scalar vector helium sensors,” used to measure the magnitude and direction of the magnetic field.

Zurbuchen said in the memo that, at the time of the February review, ICEMAG’s estimated cost has grown to $45.6 million, $16 million above its original cost trigger and $8.3 million above a revised cost trigger established just a month earlier. That cost was also three times above the original estimate in the ICEMAG proposal.

“The level of cost growth on ICEMAG is not acceptable, and NASA considers the investigation to possess significant potential for additional cost growth,” Zurbuchen wrote in the memo. “As a result, I decided to terminate the ICEMAG investigation.”

NASA will instead pursue options for “a simpler, less complex” magnetometer on Europa Clipper, although the announcement contained few details about how that will be accomplished. Scientists who were part of the ICEMAG team will be invited to remain on the overall mission science team.

“A magnetometer investigation brings significant value to Europa science and exploration,” Zurbchen said in the statement about ICEMAG’s removal. “We have enough time before launch to find such a replacement and will move quickly to implement this.”

Scientists consider the inclusion of a magnetometer particularly valuable for probing the interior of Europa, thought to contain a global ocean of liquid water. Data from the magnetometer on the Galileo spacecraft, which performed many flybys of Europa, detected variations in Jupiter’s magnetic field in the vicinity of the moon that scientists said were likely caused by the presence of an electrically conductive fluid, like water, beneath the surface.

Scientists had hoped ICEMAG would provide more detailed magnetic field measurements that could constrain the depth, thickness and salinity of the ocean. That would help scientists assess the potential habitability of Europa, a key goal of the overall Europa Clipper mission.

“The nature of the subsurface ocean and how it interacts with the surface is critical to evaluating Europa’s potential habitability,” Carol Raymond of JPL, the principal investigator for ICEMAG, said in a 2015 statement about the instrument’s selection. “Knowledge of the ocean properties helps us understand Europa’s evolution and allows evaluation of processes that have cycled material between the depths and the surface.”

Zurbuchen said that NASA was still committed to the overall Europa Clipper mission, but instituted the cost trigger process to manage the mission’s overall costs and avoid increases that could upset the overall balance of the agency’s planetary science programs. “We consider it a critical part of the mission portfolio of NASA Science, and am looking forward to see this development mature towards flight,” he wrote in the memo.

The Europa Clipper mission benefitted for years from the patronage of Rep. John Culberson (R-Texas), a House appropriator who became chairman of the subcommittee that funds NASA four years ago. Culberson was an unusually staunch advocate for both Europa Clipper and a follow-on lander, providing funding for the mission far above any NASA request for them. In the final fiscal year 2019 funding bill, passed in February but whose NASA provisions were finalized late last year, Europa Clipper received $545 million, more than double NASA’s request of $264.7 million.

Culberson, though, lost re-election last November. While NASA says it remains committed to flying Europa Clipper, the mission is unlikely to see the increased funding provided to accelerate its development. The 2019 spending bill set a 2023 deadline for launching the mission, a year later than previous bills, but NASA’s statement about the removal of ICEMAG said only that it plans to launch Europa Clipper “in the 2020s.”

Quelle: SN

----

Update: 3.04.2019

.

Europa Clipper High-Gain Antenna Undergoes Testing

A full-scale prototype of the high-gain antenna on NASA's Europa Clipper spacecraft is undergoing testing in the Experimental Test Range at NASA's Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia. Credit: NASA/Langley

It probably goes without saying, but this isn't your everyday satellite dish.

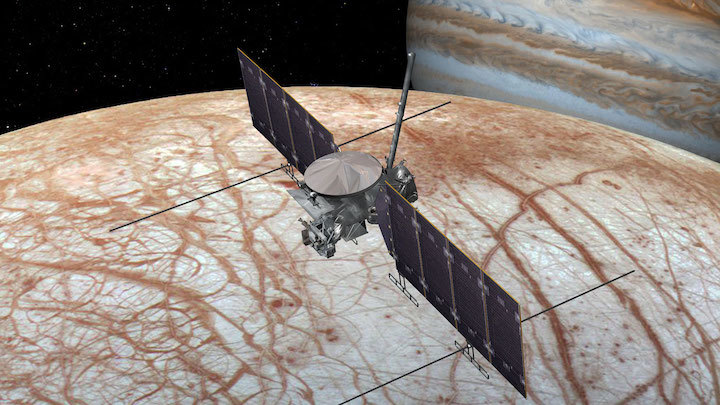

In fact, it's not a satellite dish at all. It's a high-gain antenna (HGA), and a future version of it will send and receive signals to and from Earth from a looping orbit around Jupiter.

The antenna will take that long journey aboard NASA's Europa Clipper, a spacecraft that will conduct detailed reconnaissance of Jupiter's moon Europa to see whether the icy orb could harbor conditions suitable for life. Scientists believe there's a massive salty ocean beneath Europa's icy surface. The antenna will beam back high-resolution images and scientific data from Europa Clipper's cameras and science instruments.

The full-scale prototype antenna, which at 10 feet (3 meters) tall is the same height as a standard basketball hoop, is in the Experimental Test Range (ETR) at NASA's Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia. Researchers from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, and Langley are testing the prototype in the ETR in order to assess its performance and demonstrate the high pointing accuracies required for the Europa Clipper mission.

The ETR is an indoor electromagnetic test facility that allows researchers to characterize transmitters, receivers, antennas and other electromagnetic components and subsystems in a scientifically controlled environment.

"Several years ago we scoured the country to find a facility that was capable of making the difficult measurements that would be required on the HGA and found that the ETR clearly was it,"said Thomas Magner, assistant project manager for Europa Clipper at the Applied Physics Laboratory. "The measurements that will be performed in the ETR will demonstrate that the Europa Clipper mission can get a large volume of scientific data back to Earth and ultimately determine the habitability of Europa."

Tests on this prototype antenna are scheduled to wrap up soon; however, researchers plan to return to the ETR in 2020 to conduct additional tests on Europa Clipper's high-gain antenna flight article. Europa Clipper plans to launch in the 2020s, with travel time to Jupiter taking three to seven years (depending on the launch vehicle and which planetary alignments can be utilized).

JPL manages the Europa Clipper mission for NASA's Science Mission Directorate. The multiple-flyby concept was developed in partnership with the Applied Physics Laboratory.

Quelle: NASA

----

Update: 27.04.2019

.

Europa Clipper instrument change could affect mission science

WASHINGTON — A NASA decision last month to replace an instrument on the Europa Clipper mission with a less expensive, but less capable, alternative is leaving scientists concerned about the ability of the mission to meet some of its objectives.

NASA announced March 5 that it would end development of a magnetometer called the Interior Characterization of Europa Using Magnetometry (ICEMAG) for the mission, citing cost growth and risk of further overruns. At the time of the decision, NASA said the cost of the instrument had grown to $45.6 million, three times its original estimate.

In its place, NASA will fly a “facility magnetometer” that will collect some of the same magnetic field data as ICEMAG in the vicinity of Europa, an icy moon of Jupiter. The agency subsequently said Margaret Kivelson, a planetary scientist at UCLA who also is the new chair of the Space Studies Board, will lead the development of the magnetometer.

The facility magnetometer will lack components known as scalar vector helium sensors, whose development problems led to ICEMAG’s cost overruns. Robert Pappalardo, project scientist for the mission, said in an April 23 presentation at an Outer Planets Assessment Group (OPAG) meeting here that challenges with the sensors’ fiber optic cables, which are sensitive to the temperature and radiation conditions at Jupiter, “essentially brought on its downfall.”

Instead, the facility magnetometer will rely on more conventional fluxgate magnetometers. Those devices are very precise, Pappalardo noted, but suffer offset errors over time. He estimated the original ICEMAG scalar vector helium sensors would have provided an order of magnitude improved accuracy.

The increased errors of the fluxgate magnetometers, he said, “does put at risk” some of the key, or Level 1, science requirements of the mission, notably estimating the thickness of Europa’s ice shell as well as the depth and salinity of the liquid water ocean beneath the ice. Other Level 1 science requirements aren’t affected, he emphasized.

Pappalardo showed models of the difference between potential ICEMAG and facility magnetometer measurements. With the better performance of ICEMAG, he estimated the ocean depth could be known to an accuracy of 20 kilometers. With the facility magnetometer, “ocean depth would be very poorly known: somewhere between 20 to 100 kilometers,” he said of one particular case. “That’s not a lot of information over what we have now.”

The performance of the magnetometer will also be dependent on the conductivity of that ocean. “In a high-conductivity case, we won’t know much,” he said, because of much higher errors. “We’re going to have to hope that Europa cooperates or that we can beat down this error to closer to the ICEMAG requirement.”

Pappalardo said the magnetometer team is looking for ways to improve its accuracy. That could include periodic rolls of the spacecraft to measure the ambient magnetic field and better calibrate the magnetometer.

Alternative launch plans

Overall, though, the Europa Clipper mission is moving ahead largely as planned. Lori Glaze, director of NASA’s planetary science division, said at the OPAG meeting that the mission is on track for a confirmation review this summer, at which point the agency will formally set a cost estimate.

Europa Clipper is now aiming for a launch in 2023, one year later than prior plans, a decision that project officials said was driven by workforce availability for the mission. Both NASA and Congress now support a 2023 launch date after years of debate where NASA sought to launch the mission later in the 2020s, if at all.

“I think this is one of the big wins from the president’s 2020 budget,” Glaze said. “We’re finally in sync between the president’s budget and Congress and we’re all in line with that advanced launch date of 2023.”

There’s still disagreement, though, on how to launch Europa Clipper. The fiscal year 2019 appropriations bill, as in previous years, mandated the use of the Space Launch System for the mission. SLS would allow the spacecraft to fly directly to Jupiter without the need for any gravity assists, arriving less than two and a half years after launch.

NASA’s fiscal year 2020 budget proposal, though, calls for using a commercially procured launch vehicle. That would require use gravity assist maneuvers and increase the travel time of the mission by several years, but NASA argued in its budget request that it would save “over $700 million” versus SLS.

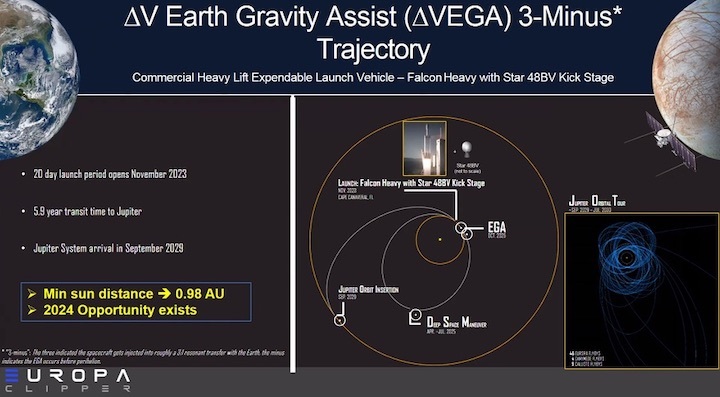

The project has been looking at a number of options for the non-SLS option. Speaking at a National Academies committee meeting in March, Barry Goldstein, Europa Clipper project manager, said one option under consideration would be a launch on a SpaceX Falcon Heavy equipped with a Star 48BV kick stage. That trajectory, known formally as Delta-V Earth Gravity Assist 3-Minus, involves a launch in November 2023 and an Earth flyby in October 2025 prior to arrival at Jupiter in September 2029.

The travel time of a little less than six years is only slightly shorter than some other alternatives previously studied. However, it has the advantage of not requiring any gravity assist flybys of Venus, with the spacecraft getting only slightly closer to the sun on its trajectory than the Earth. “That solves a world of problems on thermal management,” Goldstein said. “We no longer have the challenge of the thermal problems that we had getting close to Venus.”

A second advantage, he said, is that it offers a backup launch window roughly a year later, whereas with the Venus flyby trajectory the mission would have to wait until 2025 if it can’t launch in 2023. “We’re not 100 percent there yet, but things are looking very positive” for the new trajectory, he said.

Lander uncertainty

The outlook is less positive for a follow-on lander mission to Europa. The 2019 appropriations bill included $195 million to work on the lander, directing NASA to launch it by 2025.

The fiscal year 2020 budget request, though, included no funding for the mission, just as had been the case in previous years. The budget proposal noted that the agency estimated a lander mission to cost as much as $5 billion, and that a midterm review published last year of the most recent planetary science decadal survey recommended that a lander mission “be assessed in the context of other planetary priorities in the next decadal survey.”

In previous years, Congress has added funding to the budget for a Europa lander. However, the mission’s most influential proponent, Rep. John Culberson (R-Texas), who had been chairman of the House appropriations subcommittee that funds NASA, lost reelection last November.

At the OPAG meeting, NASA’s Glaze said that the agency will use the funding appropriated for work on a Europa lander in 2019 to support key technology development that could support such a mission in the future.

“I can assure you that the funding that we do have is being directed towards lots of early technology development and risk mitigation to prepare for a future Europa lander,” she said. “What I always say is, it’s not if, it’s when.”

Quelle: SN

----

Update: 30.05.2019

.

Inspector general report warns of cost and schedule problems for Europa Clipper

WASHINGTON — As NASA prepares for a key review of the Europa Clipper mission, a report by the agency’s inspector general warns that the mission’s launch may face delays and significant cost increases.

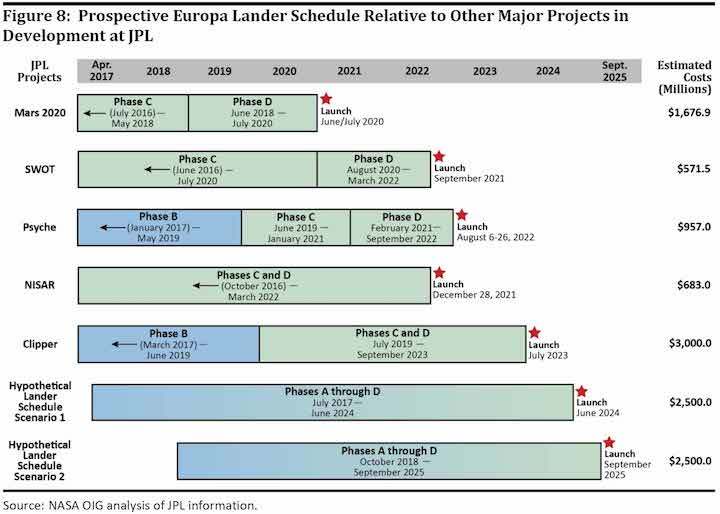

The report by NASA’s Office of Inspector General (OIG), released May 29, also said that a follow-on lander mission, which Congress has funded over the objections of the agency, is also unlikely to be ready for launch in 2025 as directed and likely will cost significantly more than expected, upsetting the balance of priorities for the agency’s planetary science missions.

The Europa Clipper mission is currently scheduled for launch in 2023 to go into orbit around Jupiter. The spacecraft will make dozens of close approaches to Europa, a large icy moon believed to harbor a subsurface ocean of liquid water. The spacecraft’s instruments will help scientists determine if Europa is potentially habitable.

Europa Clipper has advanced faster than NASA originally intended thanks to the advocacy of now former Rep. John Culberson (R-Texas), a House appropriator who secured far more money for the mission than requested. The OIG report notes that in fiscal years 2013 through 2019, Congress provided $2.04 billion in funding for Europa missions, primarily Europa Clipper, while NASA requested only $785 million in the same period.

That funding, though, may not be sufficient to keep the mission on track for a 2023 launch, a date that has already slipped a year from original plans. “Despite robust early-stage funding, a series of significant developmental and personnel resource challenges place the Clipper’s current mission cost estimates and planned 2023 target launch at risk,” the OIG report states.

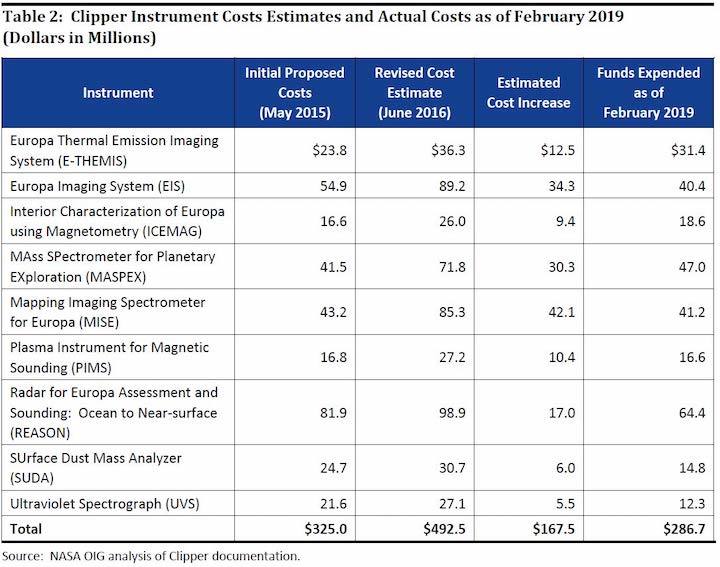

Among the issues cited in the OIG report was the selection and development of Europa Clipper’s instruments. The report found that the project selected instrument proposals with cost estimates “later found to be far too optimistic.” This was exacerbated by an instrument selection process intended to avoid conflicts of interest that largely excluded the Europa Clipper management team at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory because some of the instrument proposals came from teams also at JPL. This, the report states, may have led to integration issues, such as with a radar instrument whose design changed when the mission changed from nuclear to solar power.

NASA has since terminated one of the originally selected instruments, a magnetometer called ICEMAG, and plans to replace it with a less complex facility magnetometer. However, several other instruments have also suffered significant cost increases and are at risk of “de-scope reviews” that could alter their designs or remove them entirely.

A second issue is a workforce shortage issue at JPL, where several other missions are competing with Europa Clipper for personnel. The OIG report states that Europa Clipper was understaffed by 42 full-time equivalent positions as of October 2018, a shortfall that grew to 67 by December.

Barry Goldstein, project manager for Europa Clipper at JPL, said at a March meeting of the Space Studies Board’s Committee on Astrobiology and Planetary Science that workforce availability was a key reason the mission’s target launch date recently slipped by a year to 2023. “It was pretty clear to me that we were not going to make it,” he said. “We had just too many shortfalls in our workforce.”

Complicating the mission’s development is continued uncertainty about the choice of launch vehicle. Congress has repeatedly directed NASA to use the Space Launch System for both Europa Clipper and the later lander mission, although NASA has pushed for using a commercial launch vehicle, either United Launch Alliance’s Delta 4 Heavy or SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy, to launch the mission instead. While only SLS can send Europa Clipper on a direct trajectory to Jupiter, saving several years of travel time, NASA argued in its fiscal year 2020 budget request that using a commercial vehicle could save more than $700 million.

The OIG report found a much small cost savings by switching vehicles. NASA estimates that using an SLS will cost $876 million for Europa Clipper, versus $450 million for either Delta 4 Heavy or Falcon Heavy. When savings in mission operations created by the shorter travel time are factored in, using the SLS costs less than $300 million more than either commercial alternative.

However, the report concludes it’s too late to produce an SLS in time for a 2023 launch. NASA estimates it needs 52 months to produce a core stage for the SLS, the long-lead item for the vehicle, and six months for launch integration. “NASA would have had to order the third Core Stage in September 2018 to make a July 2023 launch window,” the report states. “As of March 2019, NASA had not ordered a third Core Stage.”

The report comes ahead of a milestone called Key Decision Point C, expected this summer, when NASA will set a formal cost and schedule estimate for the mission through a process known as joint confidence level (JCL) analysis. A similar analysis performed last October by the mission’s standing review board, according to OIG report, “determined a very low probability for a 2022 launch and provided a 70 percent confidence level for a 2024 launch at a mission cost between $3.5 billion to $4 billion.” That cost, the report noted, is far higher than earlier projections, which pegged the mission at around $2 billion, and approaches the original cost estimate for a Europa mission in the 2011 planetary science decadal that the report considered too expensive for NASA to pursue.

The OIG report was even more critical of the proposed lander mission, which Congress has directed NASA to launch by 2025. “NASA will be unable to meet a 2025 launch date due to workforce and schedule risks with the Lander and SLS development,” the report concluded. It concluded that, based on development times for flagship-class missions like the Mars 2020 rover, “the earliest it could launch would be late 2026,” a date that assumed that the mission started Phase A development at the beginning of 2019, which it has not.

“Both of the planned Europa missions are ambitious endeavors that should be grounded in realistic cost and schedule commitments,” the report concluded.” Given the unresolved technical, workforce, and budgetary challenges, we believe NASA—motivated by congressional mandates—is working towards unattainable Clipper and Lander launch dates.”

Complicating the future of the missions is the fact that Culberson lost reelection in 2018 and is no longer in Congress to advocate for the mission on the House Appropriations Committee. A version of a fiscal year 2020 spending bill approved by that committee May 22 provides $592.6 million for Europa Clipper, the amount requested by NASA, but no funding for the lander mission. The report accompanying the bill directed NASA to use the $195 million in lander funding provided in 2019 to continue technology development for the mission through 2020.

However, the bill retained language directing NASA to use the SLS to launch both missions, and also kept the requirement to launch Europa Clipper in 2023 and the lander in 2025, despite the lack of funding for the lander mission in the 2020 bill.

Quelle: SN

----

Update: 7.06.2019

.

Audit Throws Cold Water on Congress’ Europa Ambitions

A new internal NASA audit criticizes the aggressive schedule Congress has mandated for the agency’s planned missions to Jupiter’s moon Europa, finding that the in-development Europa Clipper faces stark development challenges and plans for a lander are ‘not feasible.’ A separate external audit documents ongoing cost and schedule risks facing the flagship science missions in NASA’s development queue.

NASA’s Office of Inspector General (OIG) released a report on May 29 that presents serious criticisms of the agency’s plans for two multi-billion-dollar missions to Jupiter’s moon Europa. The first, the Europa Clipper, is to make more than 40 flybys of the moon and is mandated by law to launch in 2023. However, OIG concludes it faces several budget and schedule risks. A follow-on lander mission faces an even rockier path, and OIG deems the goal of launching it in 2025 “not feasible.” OIG announced yesterday it is starting an audit of NASA’s management of its planetary science portfolio as a whole.

The aggressive plans for the Europa missions stem largely from the intense interest taken in them by Rep. John Culberson (R-TX), who chaired the House appropriations subcommittee for NASA from 2014 until his defeat in last year’s election. Optimistic that the missions would find evidence of life in the ocean beneath Europa’s icy crust, he pushed for not only generous funding for them but also statutory language mandating their launch dates and their use of NASA’s powerful Space Launch System (SLS) rockets, which are still in development. House appropriators have retained that language in their latest NASA spending proposal, even in Culberson’s absence.

The problems now facing the Clipper and lander are only the latest to afflict NASA’s largest-scale science missions, which tend to attract the most congressional interest and oversight. On May 30, the Government Accountability Office, Congress’ auditing arm, released its annual report on NASA’s most expensive projects, warning of various risks that could undermine Congress’ attempts to control their costs and schedule performance.

Clipper schedule faces substantial risks, report finds

NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) has been developing the Clipper for several years, and the mission is about to transition into its implementation phase, when spacecraft assembly begins in earnest. The mission is funded at $545 million in the current fiscal year and is projected to cost between $3.1 billion and $4 billion in total.

According to OIG, although robust funding has enabled equipment to be matured early in the mission development cycle, JPL’s Clipper management team was given insufficient time to assess proposed instruments. In OIG’s view, with more time the team might have been able to head off design problems and scrutinize cost proposals that proved to be “far too optimistic.”

After cost projections rose across the board early in development, OIG notes that NASA agreed to implement a cost monitoring process that could swiftly trigger a descoping review for troubled instruments. Earlier this year, NASA used that process when it decided to replace the Clipper’s ICEMAG instrument with a simpler magnetometer after its projected cost rose above $45 million.

Personnel shortages have been a persistent problem for the Clipper, which OIG attributes to JPL’s simultaneous commitment to five major projects, including the flagship Mars 2020 rover. OIG criticizes JPL’s practice of switching personnel between projects based on the urgency of the need for them, stating, “Given this ‘robbing Peter to pay Paul’ approach to filling critical staff vacancies, we are concerned that JPL will be unable to adequately supplement the project’s workforce with the required critical skills at critical periods in the mission’s development cycle.”

OIG also casts doubt on the congressional mandate to launch using an SLS rocket, which is intended to reduce the flight time to Europa by years. Given the SLS program’s current development and flight schedule, the office points out NASA would have had to order a rocket for the Clipper last year for a 2023 launch. While NASA has proposed using an alternative launch vehicle, OIG states the mission team has had to accommodate congressional direction to use SLS, and that the resulting indeterminacy in design “creates added risks and uncertainties for an already challenging project.”

In general, OIG concludes that the “interdependent risks” facing the Clipper must be addressed before a “realistic” launch date can be set. It further warns that an escalation of costs resulting from those risks could force NASA to divert funds from its other planetary science missions. Noting that almost $2 billion remains to be spent on the project, OIG also highlights the danger that congressional support could dwindle, particularly in view of the departure of “the mission’s most important congressional supporter.”

Intractable barriers to Europa lander plans identified

Although Congress allocated $195 million in the current fiscal year for a Europa lander, NASA has yet to formally establish it as a mission. OIG notes that even if the lander had been approved by early this year, it could have launched no earlier than 2026, assuming an aggressive development schedule.

Were the project to move ahead, the office observes that it would stretch JPL’s staff even further, exacerbating the risk of delay. Furthermore, it points out that the lander’s anticipated heft will require the use of an advanced version of the SLS that is “highly unlikely” to be available in 2025.

Beyond the practical barriers to the mission, OIG states that the lander mission was not identified as a priority by the most recent National Academies decadal survey. Given its anticipated expense, the office argues it would siphon resources from higher priority missions. Moreover, it notes that the current timetable would not permit the lander development team to take full advantage of data collected by the Clipper.

The Trump administration has already proposed canceling the lander, and NASA’s response to the OIG report notes it is now planning on a launch “no earlier than 2030.” The agency indicates it is using available funding to conduct technology development work and that JPL has already reassigned “nearly all” of the lander’s flight development personnel to other projects.

However, the mission’s fate remains up in the air. While House appropriators have proposed the lander receive no new funding, they state its current appropriation should be enough to cover next year’s expenses and that it remains a “priority.” Senate appropriators have yet to release their counterpart proposal.

GAO warns of risks to other flagship missions

Although lawmakers are broadly supportive of NASA’s work, they also keep close tabs on its project management. Directed by Congress, GAO has now been annually reviewing NASA’s performance on its most expensive projects for a decade. While the office charted significant improvement from 2012 to 2017, delays and cost overruns have ballooned since then.

GAO observes that the most recent deterioration owes to last year’s delay in the launch of the James Webb Space Telescope, which led to Congress raising the cost cap it placed on the project in 2011. While finding the mission is still on track to launch in 2021, GAO states it has already used up three months of its revised schedule reserve and remains vulnerable to further delays.

Similarly, GAO warns that as the Mars 2020 mission approaches launch, technical problems with its instruments could cause a “ripple effect” that would delay the entire project. The office notes that these problems have already led to a cost increase, as NASA revealed earlier this year, but neither GAO nor the agency have specified how much the increase will be. If it exceeds 15% of the mission’s total cost, by statute NASA must formally notify Congress and initiate a mission replanning process. A NASA spokesperson told FYI there has not been an "official declaration of [a] 15% percent [overrun] at this time," and that the agency "will endeavor to ensure the project has sufficient funding to guard against programmatically disruptive delays entering the next fiscal year."

GAO points out that NASA has proactively descoped the Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope (WFIRST) to keep the project within the $3.2 billion cost cap that Congress has placed on it. However, that cap is at the lower end of current cost projections and the mission has yet to pass the preliminary design review milestone that will establish its baseline cost. As with the Europa missions, Congress has also set specific requirements for WFIRST, including incorporating a coronagraph in its design and making the telescope compatible for use with a starshade.

In general, GAO points out a tension between NASA’s increasing commitments to major projects and the availability of resources, which has led it to propose cancelling missions such as WFIRST. However, Congress has to date proven unwilling to accept these tradeoffs. GAO reports, “Agency officials stated that they have difficulty managing the portfolio of major projects — particularly in conducting longer range planning — with continuing funding uncertainties.”

Quelle: American Institute of Physics

----

Update: 20.08.2019

.

Mission to Jupiter's Icy Moon Confirmed

An icy ocean world in our solar system that could tell us more about the potential for life on other worlds is coming into focus with confirmation of the Europa Clipper mission's next phase. The decision allows the mission to progress to completion of final design, followed by the construction and testing of the entire spacecraft and science payload.

"We are all excited about the decision that moves the Europa Clipper mission one key step closer to unlocking the mysteries of this ocean world," said Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator for the Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington. "We are building upon the scientific insights received from the flagship Galileo and Cassini spacecraft and working to advance our understanding of our cosmic origin, and even life elsewhere."

The mission will conduct an in-depth exploration of Jupiter's moon Europa and investigate whether the icy moon could harbor conditions suitable for life, honing our insights into astrobiology. To develop this mission in the most cost-effective fashion, NASA is targeting to have the Europa Clipper spacecraft complete and ready for launch as early as 2023. The agency baseline commitment, however, supports a launch readiness date by 2025.

NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, leads the development of the Europa Clipper mission in partnership with the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory for the Science Mission Directorate. Europa Clipper is managed by the Planetary Missions Program Office at NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama.

Quelle: NASA

----

Update: 11.07.2020

.

Cost growth prompts changes to Europa Clipper instruments

WASHINGTON — Cost overruns on three instruments for NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft led NASA to consider dropping them from the mission and ultimately requiring significant changes to some of them.

At a July 9 briefing to the Committee on Astrobiology and Planetary Sciences of the National Academies, NASA officials said they recently conducted “continuation/termination reviews” for the three instruments: a camera, infrared imaging spectrometer and mass spectrometer. Those reviews were prompted by cost overruns on those instruments.

“We’ve been struggling on cost growth on Clipper for some time,” said Curt Niebur, program scientist for the mission at NASA Headquarters. “Overall, we’ve been largely successful in dealing with it, but late last fall, it became clear that there were three instruments that experiencing some continued and worrisome cost growth.”

The outcome of the reviews, he said, could have ranged from making no changes to the instruments to, in a worst-case scenario, terminating the instruments. The leadership of NASA’s Science Mission Directive recently decided to keep all three instruments, at least for now.

“We are flying the entire payload, and every decision in the memo is intended to maximize the chance that we will retain the entire payload through launch,” he said.

However, there will be changes to some instruments, particularly to the Mass Spectrometer for Planetary Exploration/Europa, or MASPEX. That instrument is designed to measure the composition of the Jovian moon’s very tenuous atmosphere and any plumes of material that erupt from its surface.

MASPEX was suffering serious cost and schedule problems, Niebur said, a situation “that deteriorated further” during and after a risk assessment earlier this year. “It was really felt that significant relief was needed to avoid termination of MASPEX,” he said.

“We pulled out all the stops” to keep the instrument on the mission, he said, because of its importance in evaluating the habitability of Europa. The instrument now has a cost cap and its risk classification has changed from Class B, with a low tolerance for risk, to Class D, with a greater acceptance of risk. The mission’s overall “Level 1” science requirements will also be modified to reduce the mission’s reliance on MASPEX and the instrument’s performance requirements.

NASA also decided to replace the principal investigator (PI) of MASPEX, which had been Hunter Waite of the Southwest Research Institute. Niebur said that the institute, which retains responsibility for developing the instrument, has appointed an acting PI, Jim Burch, and will nominate a permanent replacement to be approved by NASA Headquarters.

Niebur praised Waite for an “incredible job” on MASPEX, but that new leadership was needed to keep the instrument on the mission. “To get it the final 10 yards to the end zone, we need somebody with more experience,” he said. “Jim Burch is a good match for that.”

A second instrument, the Europa Imaging System (EIS), will also get a cost cap. The camera system was suffering technical issues he described as not particularly surprising, but those problems, combined with cost growth, posed a greater concern.

One option considered by the agency was to remove a wide-angle camera (WAC) from the instrument “because it has less intrinsic scientific value” than its narrow-angle camera, Niebur said. Instead, NASA decided to keep both cameras and place a cost cap on EIS, with instructions to prioritize development of the narrow-angle camera. The mission’s Level 1 requirements will change to reduce reliance on the wide-angle camera.

“If you have to cut corners on the WAC, that’s OK,” he said. “In the worst-case scenario, if we have to go forward without the WAC, we will.”

The third instrument, the Mapping Imaging Spectrometer for Europa (MISE), did not see significant changes. Niebur said that reviewers found its design had stabilized after past issues which affected its cost and schedule. “The decision for MISE was straightforward, to adjust the cost and the schedule and to simply continue on,” he said.

These reviews are not the first time that instruments for the mission have faced problems. Last year, NASA terminated a magnetometer instrument called ICEMAG because of continued cost growth and technical problems. The agency replaced it with a simpler and less expensive magnetometer with a different PI.

Some members of the committee wondered if the instruments were being singled out for the overall cost growth in the mission, which as an agency cost commitment of $4.25 billion. Jan Chodas, project manager for Europa Clipper at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, said that the instruments used about the same amount of budget reserves as the spacecraft, or about $70 million each. However, she said that dollar amount was a much larger fraction of the overall cost to build the instruments than for the spacecraft.

Chodas said that Europa Clipper now has a launch readiness date of 2024, a year later than plans announced last year. There are launch opportunities in the summer and fall of 2024 for the mission, including an August launch window using the Space Launch System that would send the spacecraft directly to Europa. An October launch window would require Mars and Earth gravity assists, extending the flight time, but could also be done by commercial launch vehicles such as SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy.

NASA remains engaged in a debate with Congress about how to launch Europa Clipper. Congress has for several years mandated the use of SLS for the mission as well as a follow-on Europa lander mission. NASA has requested the ability to use other vehicles, citing cost savings and the lack of available SLS vehicles, which for the next several years are devoted to the Artemis lunar exploration program.

A House appropriations bill introduced July 7 would give NASA some flexibility, requiring Europa Clipper to launch on SLS only “if available,” a provision not found in previous spending bills. However, some in Congress continue to press NASA to use SLS on the mission. “NASA must increase the pace of SLS production to ensure an SLS is available for the Europa missions,” said Rep. Robert Aderholt (R-Ala.), ranking member of the commerce, justice and science appropriations subcommittee, at a July 8 markup of the bill.

Chodas said that while the Europa Clipper program has been working to support launches both on SLS and alternative vehicles, she needs a decision soon on which vehicle will launch the spacecraft. That uncertainty forced the program to delay its critical design review from August to December of this year.

“We really need a definitive decision on that launch vehicle by the end of this calendar year,” she said.

Quelle: SN

----

Update: 19.08.2020

.

Compatibility issue adds new wrinkle to Europa Clipper launch vehicle selection

WASHINGTON — A long-running debate about how to launch a multibillion-dollar NASA mission to Jupiter is now further complicated by potential technical issues involving one of the vehicles.

At an Aug. 17 meeting of NASA’s Planetary Science Advisory Committee, Lori Glaze, director of NASA’s planetary science division, said the Europa Clipper mission had recently discovered compatibility issues involving the Space Launch System, the vehicle preferred by Congress to launch the spacecraft.

“There have been some issues that have been uncovered just recently,” she said of the use of SLS for Europa Clipper. “We are in a lot of conversations right now with human exploration and others within the agency about what kind of steps we can take going forward.”

She did not elaborate on the compatibility issues regarding SLS. Such issues, industry sources say, likely involve the environment the spacecraft would experience during launch, such as vibrations. That environment would be very different for Europa Clipper, a relatively small spacecraft encapsulated within a payload fairing, than for the Orion spacecraft that will be the payload for most SLS launches.

“We are currently working to identify and resolve potential hardware compatibility issues and will have more information once a full analysis has been conducted,” NASA spokesperson Alana Johnson said in an Aug. 18 statement to SpaceNews. “Preliminary analysis suggests that launching Clipper may require special hardware adjustments, depending on the launch vehicle.”

She said the mission was working with NASA’s Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorate “to mature the launch vehicle analyses” by the time of Clipper’s critical design review, currently scheduled for December.

How to launch Europa Clipper, a decision usually made by NASA for its science missions based on technical merits and cost, has been the subject of an unusually protracted and political debate. Other than the recent compatibility issues, SLS was long the preferred choice on a technical basis, since it allowed Clipper to fly a direct trajectory to Jupiter so that it arrived within three years of launch. Alternative vehicles, like United Launch Alliance’s Delta 4 Heavy or SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy, would instead require the use of gravity assist flybys to get to Jupiter, adding several years to the flight time.

Congress has mandated the use of SLS for Europa Clipper, as well as a follow-on lander mission, including language to that effect in appropriations legislation for several years. NASA, though, has asked for relief from that requirement more recently on cost grounds. In the agency’s fiscal year 2021 budget proposal, NASA argued that the use of a commercial vehicle “would save taxpayers over $1.5 billion compared to an SLS rocket.”

Another issue is the availability of the SLS. The first three SLS rockets are earmarked for the Artemis program, including the uncrewed Artemis 1 mission launching no earlier than late 2021, the Artemis 2 crewed test flight in early 2023, and the Artemis 3 lunar landing mission by the end of 2024. Thus, the earliest an SLS would be available for launching Europa Clipper would be 2025, even though the spacecraft itself will be ready to launch by 2024.

Glaze noted that availability of an SLS before 2025 “is not guaranteed” given demand for the vehicle for the Artemis program. “The launch vehicle remains very uncertain,” she said. “It is still a concern and an increasing concern.”

Europa Clipper has, for now, been keeping open both the option of launching on SLS as well as on a commercial alternative. Doing so, Glaze said, costs the mission about $30 million a year, but will increase if NASA doesn’t finalize the launch vehicle by the time of December’s critical design review.

The House version of a fiscal year 2021 spending bill would give NASA some wiggle room. The bill continues to call for launching Europa Clipper on SLS, but only “if available,” a provision not included in appropriations bills in past years that required the use of SLS without exception.

Despite the new language, one House appropriator continued to call for using SLS for Europa Clipper. “NASA must increase the pace of SLS production to ensure an SLS is available for the Europa missions and other future science missions, in addition to meeting all the human exploration needs,” said Rep. Robert Aderholt (R-Ala.), ranking member of the commerce, justice and science appropriations subcommittee, during a July 8 markup of the bill.

Quelle: SN

----

Update: 5.09.2020

.

NASA's Europa Clipper will find out if Jupiter's icy moon is habitable

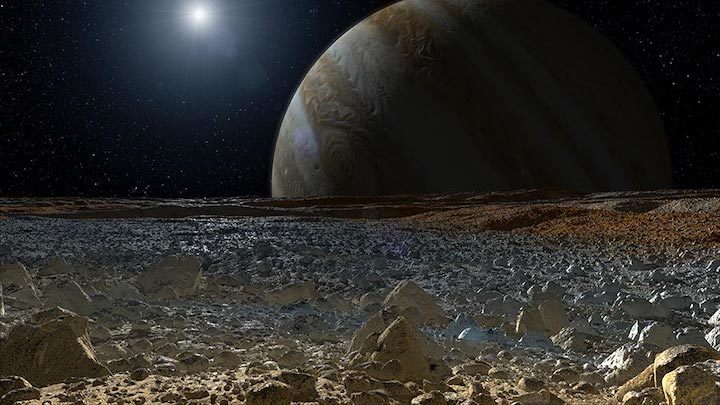

Water. Energy. Chemistry. Europa has all the necessary ingredients for life. And unlike Mars or other potentially habitable worlds, Jupiter’s icy moon doesn’t have just a little water — it boasts twice as much of the liquid as Earth’s oceans combined.

Despite Europa's deep-space locale, the moon doesn’t completely freeze because Jupiter’s hulking gravity heats up its core. As the most massive planet in the solar system, Jupiter constantly tugs on Europa, creating tides and, potentially, hydrothermal vents that can mix up life-enabling chemical cocktails below the moon's icy shell.

All that water, heat, and mixing makes Europa one of the most promising places to find alien life in our solar system. And that’s why NASA is building a dedicated mission to the ocean world called Europa Clipper.

The primary goal of Europa Clipper is to find out if the moon is actually habitable. And in just a few short years, around 2023, the spacecraft will be ready for launch. So, less than a decade from now, depending on the space agency’s final rocket choice, Europa Clipper should reach its destination.

Once there, the spacecraft's instruments will search Europa' surface and "taste" its thin atmosphere, looking for signs of recent eruptions of water. The mission also should reveal secrets of the moon’s icy shell and aqueous interior, despite never touching down on its surface.

Those insights will be vital to taking the next step: Landing a spacecraft on Europa.

“The Europa Clipper mission will take a profound step in advancing our understanding of habitable environments beyond Earth,” wrote NASA’s Samuel Howell and Robert Pappalardo, both Europa Clipper team members, in the journal Nature Communications earlier this year.

The push for a Europa mission

In July 1979, NASA’s Voyager 2 spacecraft returned the first close-up images of Jupiter and its moons. This brief flyby was enough to thrill astronomers. The probe’s grainy images revealed Europa was covered in a young, icy crust, but it would take more than a decade before another spacecraft visited the fascinating moon.

NASA’s Galileo spacecraft, a Jupiter-orbiting satellite that launched in 1989, provided the follow-up. But Galileo didn’t operate entirely as expected thanks to a malfunctioning antenna. It only gathered a limited dataset, making about a dozen close flybys of Europa.

Nonetheless, Galileo discovered that Europa has an induced magnetic field, which led them to detect its global saltwater ocean. Those glimpses also showcased the moon’s complex geology, including a detailed look at its cracked and chaotic surface. As the last mission to perform detailed studies of Europa up close, scientists still depend on Galileo’s three-decade-old data to make breakthroughs today.

In fact, in a paper published in Nature Astronomy in 2018, researchers used old Galileo data to find the best evidence yet for plumes of water ice streaming off Europa. The team behind the study looked at changes in the moon’s magnetic field and plasma and traced back where the spacecraft was when it saw them. It turned out, the observations focused on an area already suspected to have heat welling up from Europa’s interior.

And despite limited up-close data of Europa, astronomers have been able to make some new discoveries from roughly 400 million miles away. On multiple occasions, NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope has spotted evidence for plumes of water erupting from Europa’s ocean out through the icy shell and into icy space.

Meanwhile, models suggest that Europa could also hide the kind of hydrothermal vents that fuel entire deep-ocean ecosystems on Earth. Some research even hints that the moon’s ocean could have an Earth-like chemical balance capable of supporting life, even without hydrothermal vents.

All of these results only make astronomers want to return to Europa more than ever.

Building Europa Clipper

Soon, they’ll have their chance. Last year, NASA formally announced that Europa Clipper would move into its final design phase, the last step before actual construction and testing begins. And it could even launch as soon as 2024, if it’s ready in time.

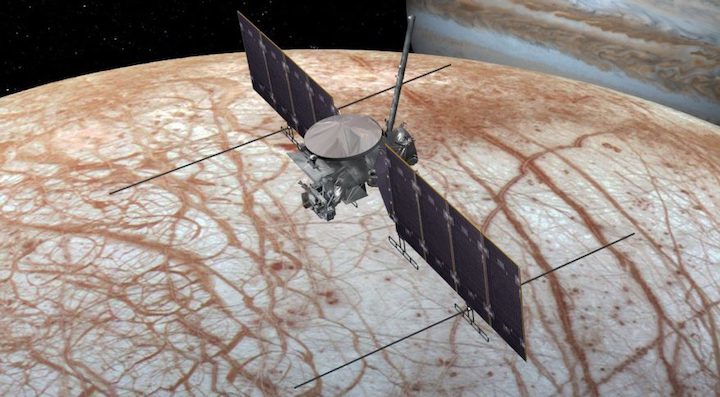

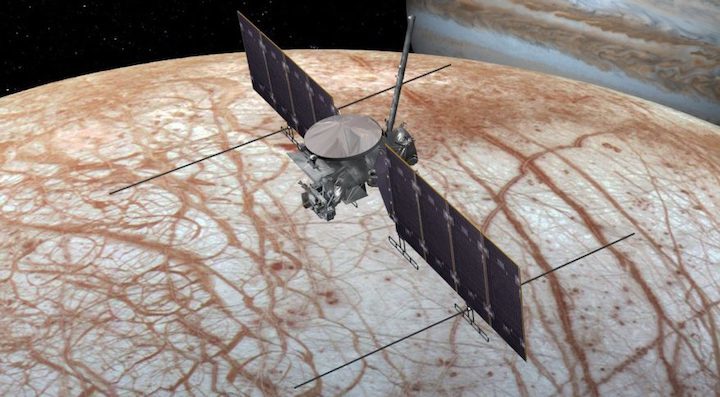

The mission’s driving purpose is to find out whether the conditions for life could exist on Europa. To do this, the spacecraft will orbit Jupiter on a long, looping path that allows for 45 flybys of the icy moon. Some passes will take the spacecraft within just 16 miles (25 km) of Europa's icy surface.

Such an ambitious path proved pivotal to the mission getting funding, too. In the past, scientists had proposed Europa spacecraft that orbited the moon itself. But at Europa’s distance, Jupiter emits intense radiation. A Europa-orbiting spacecraft would need serious shielding to endure prolonged exposure to this harsh environment. and the cost of providing that protection proved too much. So, after several failed mission proposals, engineers finally came up with an alternative path to explore Europa. By relying on long, elliptical loops around Juipter, the Clipper mission limits the amount of radiation it's exposed to, which helped reduce cost.

Despite gathering fewer views of Europa’s surface than if it orbited the moon itself, the science the spacecraft performs will still be a game-changer.

Europa Clipper has nine instruments, ranging from high-resolution cameras that will offer detailed views of the surface, to ice-penetrating radar that will let astronomers gauge the thickness of Europa’s frozen shell. A gravitometer will confirm that Europa’s ocean exists, plus other details, while a spectrometer will allow scientists to suss out the chemical fingerprints of specific types of ice on the moon, revealing what mix of elements spill onto the surface from the ocean below. The mission will also carry a magnetometer. By studying the world’s magnetic field, astronomers hope to get a better grasp on the depth and salt content of Europa's oceans.

Taken together, Europa Clipper's instrument suite should revolutionize our understanding of the ocean moon — not just on the outside, but on the inside, too.

The mission’s biggest lingering question is how exactly it will reach its target. Europa Clipper could arrive around Jupiter anywhere 2.5 to 6 years after launch, depending on which rocket the mission relies on.

When the U.S. Congress was debating Europa Clipper, legislators secured key votes to approve funding by requiring the spacecraft fly atop NASA’s long-delayed and much-maligned Space Launch System. The rocket is being built in Alabama, where it provides jobs for the constituents of certain senators and members of congress. But after years of delays, it’s still never flown. NASA itself has suggested not using the rocket because it’s massively more expensive than other options, like SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy and United Launch Alliance’s Delta IV rockets.

Plus, Europa Clipper has already had to make cost cutting decisions due to budget overruns, as reported by the website SpaceNews. So, ultimately, getting Europa Clipper off the ground on schedule and on budget could require new legislation.

Laying the groundwork for a Europa lander

Europa Clipper’s launch vehicle wasn’t the only choice that congress mandated by law, either. The space agency also is required to later send a lander to Europa, something it’s so far been reluctant to commit to.

“NASA’s a big bureaucracy. It's difficult to get them to move or do things, so it was necessary for me to write it into law,” former Congressman John Culberson of Texas told Astronomy in 2015. “In fact, [this] is the only mission that it is illegal for NASA not to fly. And I made certain of that.”

Undoubtedly, Europa’s underground ocean is its most interesting feature. And if there’s life on the world, it’s likely beneath the surface. But getting down there will not be easy. In the past, scientists have suggested landing probes on the surface that could melt through miles of ice and deploy submarines to explore the vast oceans.

Sending a lander would be expensive and technologically challenging, however. And more importantly, though NASA makes valiant efforts to avoid it, the spacecraft could carry earthly lifeforms with it, compromising any data and possibly bringing invasive microbes to a pristine alien environment.

That’s part of the reason why, despite the legal requirement, NASA has yet to formalize a plan to build a Europa lander. However, the scientific community has since proposed a number of potential options to explore Europa’s surface — as well its ocean below.