6.03.2019

ESA GIVES GO-AHEAD FOR SMILE MISSION WITH CHINA

ESA GIVES GO-AHEAD FOR SMILE MISSION WITH CHINA

The Solar wind Magnetosphere Ionosphere Link Explorer, Smile, has been given the green light for implementation by ESA’s Science Programme Committee.

The announcement clears the way for full development of this new mission to explore the Sun-Earth connection, which will be conducted in collaboration with China.

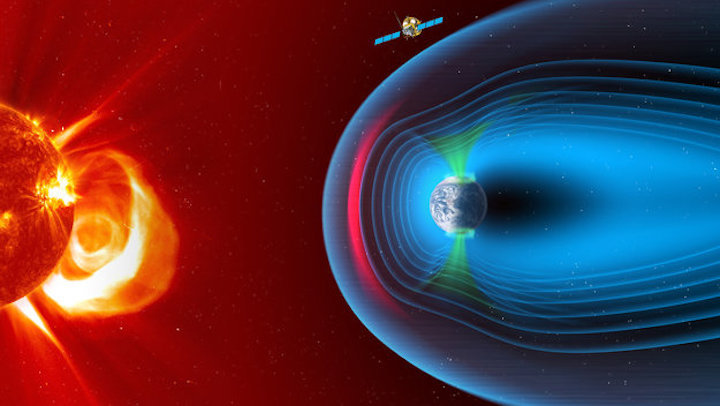

Smile is expected to revolutionise scientists’ understanding of the physical processes taking place during the continuous interaction between particles in the solar wind and Earth’s magnetic shield – the magnetosphere.

The mission will be a major scientific endeavour in collaboration between ESA and China, following on from the success of the Double Star / Tan Ce mission which flew between 2003 and 2008. Unlike Double Star, which started out as a China-only project, Smile is envisaged from the start as a joint ESA-China mission.

The scientific collaboration began with two workshops – one held in China, one in Europe – that were held to facilitate collaboration between Chinese- and European-based researchers. This was followed by a joint call for proposals that was issued in January 2015 by ESA’s Directorate of Science and Robotic Exploration and the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS).

Following selection in November 2015, detailed studies by ESA, CAS, three European industrial contractors and the Science Study Team have finalised the mission architecture, including the space and ground elements that are required to fulfil the science requirements.

Under current plans, the 2200 kg spacecraft will be launched by a European Vega-C rocket or Ariane 6-2 in 2023, and subsequently be placed in a highly inclined elliptical orbit around Earth. Every 51 hours, Smile will fly out to 121 000 km – almost one third of the distance to the Moon – giving it a prolonged view of Earth’s northern polar regions. It will then return to within 5000 km of the planet in order to download its treasure trove of stored data to an ESA ground station in Antarctica and the CAS ground station in Sanya, China.

From this unusually elongated orbit, the satellite will be able to make continual observations of key regions in near-Earth space over a period lasting more than 40 hours. These will include simultaneous images and movies of the magnetopause – the boundary where Earth’s magnetosphere meets the solar wind – as well as the polar cusps, and the region illuminated by the Northern Lights, or aurora borealis.

Smile will offer scientists the chance to observe these key regions of Sun-Earth interaction for such long periods of time for the first time. The prime mission will last three years.

The science payload consists of four instruments: two from Europe and Canada, and two from China.

The innovative wide-field Soft X-ray Imager (SXI), provided by the United Kingdom Space Agency and other European institutions, will obtain unique measurements of the regions where the solar wind impacts the magnetosphere. The Canada-led Ultra-Violet Imager (UVI) will study global distribution of the auroras.

The two Chinese instruments, the Light Ion Analyser (LIA) and Magnetometer (MAG), will measure the energetic particles in the solar wind and changes in the local magnetic field.

ESA is also responsible for the payload module, spacecraft test facilities, launcher, launch campaign, the primary ground station; ESA will share science operations with CAS. A contract for industry to build the payload module will be announced in due course, and all spacecraft assembly and test activities will take place in Europe.

The National Space Science Center (NSSC/CAS) in China is responsible for the spacecraft platform, spacecraft testing, and mission and science operations. The platform will be built in Shanghai by the Innovation Academy for Microsatellites (IAMC/CAS).

According to ESA’s Smile study scientist, Philippe Escoubet, the mission will enable important breakthroughs in studies of the ever-changing interaction between Earth’s magnetic field and the solar wind.

“Smile will provide the first X-ray images and movies of the region where the solar wind slams into the magnetosphere,” says Philippe. “It will also provide the longest-ever ultraviolet imagery of the northern aurora, enabling researchers to see how the aurora changes over time and to understand how geomagnetic storms evolve.”

Quelle: ESA

----

Update: 8.03.2025

.

When two become one: engineers get Smile ready for launch

At the European Space Agency’s technical heart in the Netherlands, engineers have spent the last five months unboxing and testing elements of Europe’s next space science mission. With the two main parts now joined together, Smile is well on its way to being ready to launch by the end of 2025.

Smile will give humankind its first complete look at how Earth reacts to streams of particles and bursts of radiation from the Sun. By improving our understanding of the solar wind, solar storms and space weather, Smile will fill a stark gap in our understanding of the Solar System. To make sure that the mission is a success, our teams are working tirelessly behind the scenes.

Watch the video below to get a glimpse into what we’ve been up to recently. [Text continues after video]

Access the video

As a 50–50 collaboration between ESA and the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), Smile is a truly international effort. Pieces of the spacecraft have been built by teams across Europe and China, and are now finally united at ESA’s technical heart (ESTEC).

Smile’s crucial ‘payload module’ – which contains three of its four scientific instruments – was built by Airbus in Spain on behalf of ESA. This major piece was the first to arrive at ESTEC in September last year.

The arrival of the payload module kicked off a year-long integration and testing phase, where colleagues from ESA, Airbus and CAS are all working together at ESTEC to prepare the spacecraft for flight. Step one was to put the payload module through a gruelling test regime to make sure that it was absolutely ready to work perfectly as a complete unit in the challenging space environment.

The process was not always smooth sailing. On 21 November 2024, Airbus and ESA teams looked on nervously as the spacecraft’s 3 m-long magnetometer boom refused to lock into place. Engineers entered into intense discussion and very quickly discovered the cause: a bundle of cables that was too stiff and not mounted correctly.

The team fixed the issue immediately by loosening the bundle and mounting it slightly differently. They successfully released the boom again the following day. A round of applause filled the room when the boom clicked into place. Click on the image below to find out more about the magnetometer boom and the little instrument that sits at its end.

“Overall, the arrival and testing of the payload module went really well and we are confident that the instruments on board are going to collect fantastic scientific data once in space,” says ESA’s David Agnolon, who is managing the European side of the Smile project. “This is the first time that ESA and China are collaborating on a project of this type and scale, and we have already overcome many challenges thanks to an excellent spirit of cooperation on both sides.”

One of the biggest challenges that David refers to relates to working with colleagues in another continent during the COVID-19 era. In 2022, for example, Airbus sent a model of the Smile payload module to China for testing. But because of travel restrictions, Airbus and ESA colleagues were not able to support the testing of their own hardware, and the teams had to resort to ‘online engineering’.

Fortunately, colleagues from around the world are now able to work harmoniously at ESTEC, sharing cultures and traditions as well as engineering knowledge.

On 9 December 2024, Smile’s ‘platform’ arrived on a dedicated flight from Shanghai, together with 15 engineers and managers from CAS. The platform contains the fourth scientific instrument, as well as everything else that the spacecraft needs to function, including the modules responsible for powering, steering and controlling the spacecraft.

Getting Smile’s platform to the Netherlands was no easy feat. It was the first time a spacecraft platform was exported to Europe from China. Special authorisations were needed, for example from Amsterdam Schiphol Airport, Air China Cargo, the Dutch and Chinese civil aviation authorities and ESA’s own transport company.

The arrival of the platform was ultimately delayed because of the huge amount of documentation involved, in particular for the ammonia in the heat pipes labelled as ‘dangerous goods’.

Access the video

Finally, on 21 January 2025, Smile’s payload module could be connected to the platform with 120 bolts. This delicate procedure required perfect precision, with about twenty people from ESA, CAS and Airbus surrounding the spacecraft, fully focused on the task in hand. The engineers wore white cleanroom suits, hair and beard nets, and shoe coverings to protect the spacecraft from dust and dirt.

As they say, the devil is in the detail, and the team quickly encountered an obstacle. They realised that when they would place the payload module onto the platform, some cables would slightly cover up the bolts, making the attachment tricky.

Engineers put their heads together (literally – the cleanroom environment can be busy!) and quickly came up with a solution. They made a last-minute adjustment to the integration procedure, deciding to place some bolts before lifting the payload module, to ensure that the later attachment would go as smoothly as possible.

Finally, the payload module was ready to move. Engineers attached hooks and used a hoisting device to lift it very slowly, at about a centimetre per second. Smile’s ‘assembly, integration and testing’ manager from ESA, Benjamin Vanoutryve, looked on attentively.

“This moment was finally happening, after so many years of meticulous preparation work on two sides of the world. In just a moment, we would finally see ‘our’ Smile spacecraft as a real object for the first time,” says Benjamin.

An Airbus engineer used a remote-control belt to carry the payload module over to the platform, and lower it slowly, millimetre by millimetre, to line up perfectly with the platform below. When the two were separated by just 20 cm, Airbus handed over to CAS, who took care of the very final attachment. CAS and Airbus colleagues in safety harnesses up on aerial platforms closely monitored the operation.

As the payload module was lowered into place, the engineers could start bolting the two parts of the spacecraft together. For the first time, the teams are now dealing with a complete spacecraft.

So, what’s next for this little spacecraft with big ambitions?

From this month, Smile will be tested for the first time as a complete unit. Engineers will have to get it to pass tough checks with flying colours before being allowed out on its own, including making sure that the entire system can operate properly in the vacuum of space, that the different parts of the spacecraft don’t create too much electromagnetic disturbance for other parts, and that the violent launch won’t shake the spacecraft apart.

Airbus engineers will continue to support the CAS and ESA teams throughout the entire test campaign to ensure that the platform and payload module work perfectly well together and help to resolve any issues.

By September 2025, Smile should be ready to go, and our ESTEC colleagues will wave goodbye as it ships off to Europe’s Spaceport in French Guiana. From there, the team will prepare Smile for launch on a Vega-C rocket, hopefully by the end of this year.

Quelle: ESA

----

Update: 17.07.2025

.

Smile passes gruelling set of tests

All its parts have been built and put together. It has been wrapped in shiny gold insulating foil. Its launch is getting closer. But the Smile spacecraft had one major phase to pass before it could be certified ready for space – and it involved testing, testing and yet more testing.

Since March, engineers have been busy getting Smile through tough checks at ESA’s technical heart, ESTEC, in the Netherlands. After all, if you’re going to spend years developing a spacecraft to watch how Earth’s magnetic field responds to the solar wind, you’d better make sure it can handle the shaky rocket launch, the vacuum of space, and the extreme temperatures it will face in orbit around Earth.

With Smile being a joint effort between the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), engineers from both organisations, as well as from the companies Airbus and European Test Services, have been working together.

Test 1: Smile meets the spikes

This testing phase began when engineers moved Smile into the Maxwell Test Chamber.

Like most spacecraft, Smile is very sensitive. It is designed to pick up weak magnetic field signals, as well as very faint light from the magnetic bubble surrounding Earth, and ultraviolet light from the auroras. At the same time, it will transmit a lot of data down to Earth with high-power antennas.

Engineers used the absorbent nature of Maxwell’s spiky walls to make sure that there was no ‘crosstalk’ between all the spacecraft’s electronics.

As Smile Systems Engineer Chris Runciman puts it, "it’s like when you have your phone beside a speaker and it starts making funny noises before your text message comes in" – that interference is exactly what we don’t want to see happening in Smile.

Knowing that Smile’s electronics are not interfering with each other, our engineers are now confident that its science instruments will work excellently in space, and that we will get the images we need of Earth’s magnetic environment.

The Maxwell Chamber tests also confirmed that Smile is safe to launch inside the Vega-C rocket that will take it to space. Because the rocket carries lots of electronics, we had to be sure that they will not be disturbed by Smile, and vice versa.

Test 2: hop on the scales

Our engineers quickly moved Smile out of the Maxwell Chamber and onto the next set of tests: measuring how much it weighs and where exactly its centre of gravity is.

Engineers spent four days making these measurements using some of the most advanced scales in Europe. Thanks to the information they collected, we know that the spacecraft is compatible with Vega-C, and spacecraft controllers have all the knowledge they need to properly manoeuvre Smile once it is in orbit around Earth.

Test 3: feeling all shaken up

At the end of April, the spacecraft was placed on the ‘shaker’. Standing on the shaker feels like experiencing an earthquake; it’s a simulation of the intense vibrations Smile will feel as its rocket takes off.

Smile got through the gruelling test in one piece, giving us complete confidence that it will make it to space in perfect working order.

Interlude: Smile takes a stretch

A quick stretch before our final big test. Smile’s solar panels are vital for supplying power to its onboard systems and scientific instruments. In other words – no solar power, no mission!

During the launch, the solar panels will remain safely folded up. Once in space, a little mechanism will activate that lets them fully stretch out. On 15 May, engineers checked that this mechanism works for both ‘wings’. As the image below shows for one wing, Smile gets another green tick.

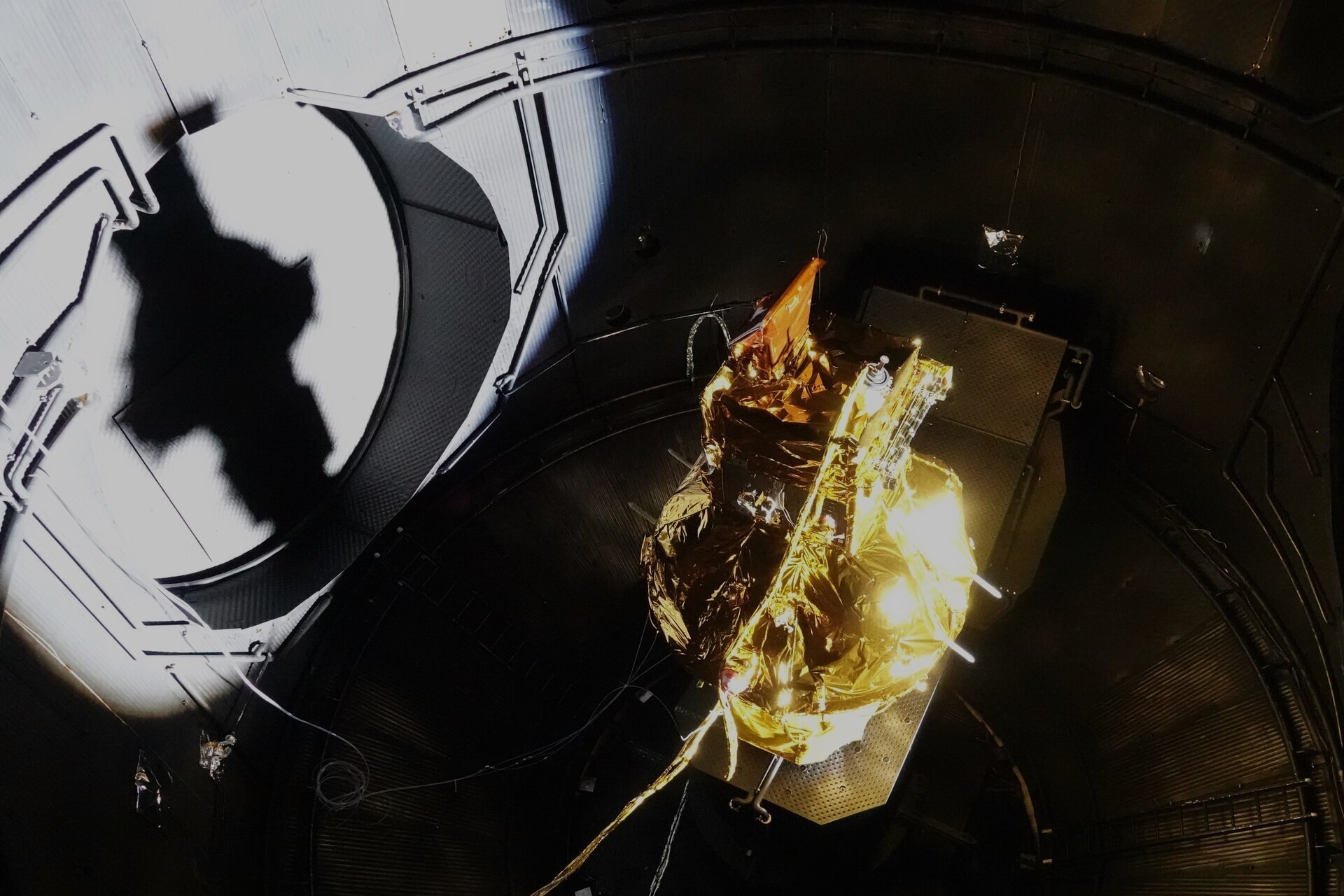

Test 4: Smile enters the darkness

Finally, at the end of June, Smile was put into the Large Space Simulator – Europe’s largest vacuum chamber. This massive machine does what it says on the tin, recreating the strange vacuum and tough temperatures of outer space. It even includes a Sun simulation to imitate how Smile will feel super-hot on its Sun-facing side, and super-cold on its shaded side.

It’s the final, and possibly most complicated, part of the spacecraft environment testing phase. In early July, Smile Project Manager David Agnolon confirmed its success.

“Running 24/7, the thermal test has been very intense but highly satisfying. It was completed smoothly, in record time and yielded very good results. This outcome is largely thanks to the impressively good preparation and excellent execution of the team,” says David.

“We can now say that Smile is 100% ready for space and ready to deliver its scientific data to better understand our planet’s magnetic shield and how it responds to the solar wind. This is testament to years of hard work from industry across Europe and China.”

The images below show more of the space environment testing at ESTEC.

Last week, Smile was carefully removed from the Large Space Simulator. But it’s still not quite ready to go.

During the second half of July, engineers are re-checking parts of two of Smile’s science instruments – the boom that holds its magnetometer at the end, and the cover of its ultraviolet camera – to make sure nothing was damaged during the thermal testing. After that, Smile will go through a last few software and operational tests, before finally being packed up safely, ready for shipping to Europe’s Spaceport in French Guiana around two months before launch.

Quelle: ESA