3.03.2019

The extinct airline's moon project never got off the ground, but it can teach us plenty about today's commercial space race.

In 1964, Austrian journalist Gerhard Pistor walked into a Vienna travel agency with a simple proposition. He’d like to fly to the moon, and if possible, he’d like to fly there on Pan Am.

The travel agency, presumably dumbfounded by this request, decided to simply do its job and make the ask: It forwarded the impossible request to the airline, the legend goes, where it attracted the attention of Juan Trippe, the notoriously brash and publicity-thirsty CEO of Pan American World Airways, the world’s most popular airline. Trippe saw a golden opportunity, and the bizarre request gave birth to a brilliant sales ploy that cashed in on the growing international obsession with human spaceflight: Pan Am was going to launch commercially operated passenger flights to the moon. Or, at least, that’s what it was going to tell everyone.

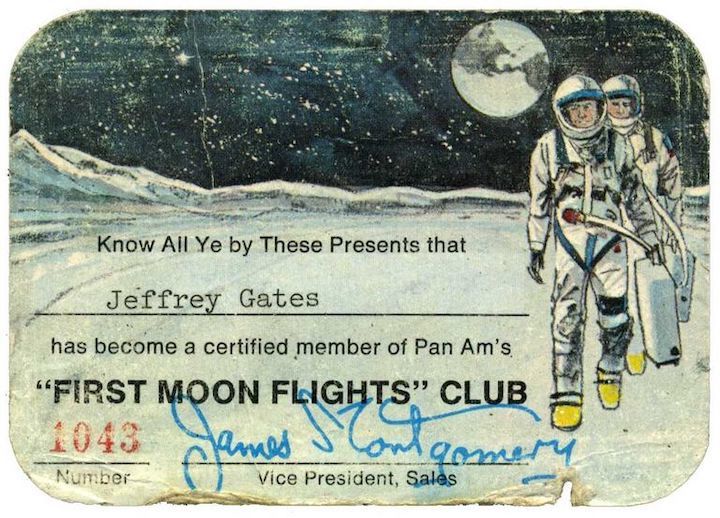

In hindsight, it’s beyond ludicrous. NASA wouldn’t land men on the moon for five more years; the promise of lunar getaways on a jetliner sounds like a marketing scam at worst, and the most preposterous extension of 1960s techno-optimism at best. And yet, in a striking parallel to today’s commercial space race, would-be customers put down their names on a waiting list for their chance to go to space, joining Pan Am’s “First Moon Flights” Club.

If history is a guide, then Virgin Galactic, SpaceX and Blue Origin should be cautious. Pan Am dissolved in 1991 without ever getting close to launching a spacecraft. Even when it promised the moon and the stars, the airline was far closer to financial oblivion than it was to the cosmos.

Anything Is Possible

“I think it has to be seen in the context of the sixties. Everything seemed possible in the sixties, technologically,” says Bob Gandt, a former Pan Am pilot and the author of Sky Gods. That’s why he and other pilots picked Pan Am, after all, when they could have flown for any airline. “We chose Pan Am because they had this wonderful promise.”

With its lunar dream, the airline tapped into a collective euphoria sparked by such milestones as NASA’s Saturn V rocket and later Neil Armstrong’s trek across the moon’s surface. The Space Race was in full swing, and the United States was determined to best the Soviet Union in its pursuit of interstellar glory. Science fiction novels depicted a lunar surface crowded with colonies, while scientific studies waded into humanity’s inevitable spacefaring future, characterized by lunar crop fields and encounters with aliens.

In other words, everything was in place for Pan Am’s moon mania. Pistor’s initial moon-flight booking spawned a craze that would ultimately see Pan Am field 100,000 moon reservation requests under its First Moon Flights Club, which finally closed in 1971. All members were given cards with a number—an indication of one’s place on the ever-growing queue of layman astronauts.

And then Pan Am got a little boost from Hollywood.

2001: A Space Odyssey

Before the Star Child, before the monolith, before HAL 9000’s rendition of “Daisy,” came a detail you might have missed about Stanley Kubrick’s science-fiction epic, 2001: A Space Odyssey. It had product placement for Pan Am’s moon ambitions.

In one scene, the fictional Pan Am “Space Clipper”—emblazoned with the carrier’s unmistakable logo—docks inside a gigantic space station miles above Earth. The image delivered a stirring visual of Pan Am’s idea, and also convinced more than a few Americans that the airline’s moonshot was legit.

Jeff Gates, an early member of the First Moon Flights Club, recalled his impression of the scene in an article for Smithsonian, writing that the movie “made that future easy to imagine. With flight attendants preparing food and attending to passengers, everything but the view out the window was something I had already experienced.”

Margaret Weitekamp, curator of the space history department at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, echoes Gates’ assessment. She told Popular Mechanics:

“I think if people were excited about a First Moon Flight Club they also may have been inspired by this vision of Pan Am flying paying passengers up to an orbiting space station that they had just seen so persuasively illustrated in 2001.”

Kubrick’s space masterpiece came out in 1968, just as NASA’s triumphs in the real world added an element of realism to Pan Am’s dream. The moon landing, for one, opened the floodgates for prospective astronauts around the world.

"There was a steady, albeit small, flow of requests for reservations after Mr. Pistor's inaugural booking," Peter McHugh, Pan Am's senior vice president of marketing told the Florida Sun Sentinel in 1989. "The real deluge came after the successful Apollo 8 mission on December 22, 1968, and the lunar landing of the Apollo 11 on July 20, 1969. During those months, the concept of scheduled passenger service to the moon quickly shifted from science fiction to the realm of the possible."

The moon landing wasn’t the only thing getting the public excited. By the late '60s, aviation in general had evolved from a niche and expensive luxury into a massive commercial industry enjoyed by middle class families. The remarkable change from dangerous and flimsy aircraft to the modern airliners we know today came about in just three decades, says Weitekamp. The blinding pace of innovation lent credence to the belief that Pan Am could very well deliver on its futurist promises.

She said:

“If you think about people who have lived through that pace of change ... it’s not that far of a logic leap to think that by the year 2000—which sounded impossibly foreign—that given another 31 years, given how far aviation had come in the previous years, that space flight would go in the same direction from being something that was elite, exclusive, controlled, to something that was an everyday conveyance for people.”

A Bet on the Future

That hope and expectation continued to balloon, with Pan Am touting the moon program in national media throughout the 1970s and '80s. Eventually, though, airline deregulation helped bring about Pan Am’s demise. But the legacy of its moon project’s optimism—and its ultimate failure—live on.

On the one hand, yes, Pan Am’s moon gambit was an obvious marketing ploy. But Bob Gandt maintains there was more to it. “It was simply a bet on the future,” he tells Popular Mechanics. “In '69, when they first set foot on the moon, and pulled it off and got back, I was absolutely certain, that there’d be a colony ... and we’d start heading to Mars.”

For Gandt, humanity carving out an existence on the moon is still an inevitability. It will be the architects of today’s commercial space race that will get us there, he says. “There will [one day] be flights to the moon, a colony on the moon, a base that you can go to. It will be driven not just these billionaires but competition with China.”

Truly, Pan Am was ahead of its time. To understand the lunar projects of Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk and Richard Branson, it makes sense to start with Pan Am’s moon program, which coupled the same sense of ambition and grandeur with a marketing savvy unparalleled by anything before it. With its First Moon Flights Club, Pan Am laid the conceptual framework for space tourism, honing an idealism that still holds true among modern giants like Virgin Galactic, Blue Origin and SpaceX.

SpaceX’s Elon Musk, for example, has vowed to make humanity an “interstellar species” that freely roams the cosmos. But just as Pan Am struggled to make its moon program a reality, commercial aerospace players like SpaceX and Virgin Galactic have so far failed to deliver on their grandiose schemes.

In 2009, Virgin Galactic CEO Richard Branson gave his company an 18-month timeline to make its first successful space flight. The reality came a decade later—after numerous other promises and the VSS Enterprise disaster—when the company launched its first paying passenger into orbit earlier this month. SpaceX, too, though less intent on fostering a space tourism boom like Branson, had to endure intense growing pains before it could even get a rocket into orbit.

“The rhetoric surrounding commercial space venues is still much more aspirational than reality,” says Margaret Weitekamp. “And I will be very curious to see what Virgin Galactic or some of these other companies ultimately are able to do.”

Despite the setbacks, the current crop of aerospace juggernauts have their sights set onmoon landings in the near future, and are selling tickets for a quarter-million dollars.

And so far, the waiting lists remain cluttered with names that still haven’t left the Earth.