3.03.2019

A trial NASA rover mission in the Mars-like Atacama desert has successfully recovered subterranean organisms -- strange, scattered, salt-resistant bacteria that could lead the search for Martian life deeper underground

A trial NASA rover mission in the Mars-like Atacama desert.

A robotic rover deployed in the most Mars-like environment on Earth, the Atacama Desert in Chile, has successfully recovered subsurface soil samples during a trial mission to find signs of life. The samples contained unusual and highly specialized microbes that were distributed in patches, which researchers linked to the limited water availability, scarce nutrients and chemistry of the soil. These findings, published in Frontiers in Microbiology, will aid the search for evidence of signs of life during future planned missions to Mars.

A rover rehearsal in the most Mars-like environment on Earth

"We have shown that a robotic rover can recover subsurface soil in the most Mars-like desert on Earth," says Stephen Pointing, a Professor at Yale-NUS College, Singapore, who led the microbial research. "This is important because most scientists agree that any life on Mars would have to occur below the surface to escape the harsh surface conditions where high radiation, low temperature and lack of water make life unlikely."

He continues, "We found microbes adapted to high salt levels, similar to what may be expected in the Martian subsurface. These microbes are very different from those previously known to occur on the surface of deserts."

In 2020 both NASA and the European Space Agency will embark on missions to deploy rovers on the surface of Mars. They will search for evidence of past or present life and for the first time, drill below the surface where refuges for simple microbial life may still exist.

To help ensure that these space missions succeed, technology is rigorously tested on Earth first.

"The core of the Atacama Desert in Chile is extremely dry, experiencing decades without rainfall. It has high surface UV radiation exposure and is comprised of very salty soil. It's the closest match we have on Earth to Mars, which makes it good for testing simulated missions to this planet," argues Pointing.

Life is patchy in extreme environments - so Mars rovers will need to dig deep

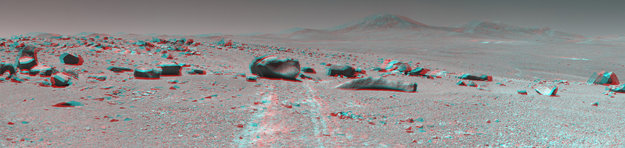

An autonomous rover-mounted robotic drill and sampling device, funded by NASA designed by Carnegie-Mellon's Robotics Institute, was deployed in the Atacama Desert to test if it could successfully recover sediment samples down to a depth of 80cm. Pointing and his colleagues compared samples recovered by the rover to soil samples carefully taken by hand. Using DNA sequencing, they found that bacterial life in the sediments recovered by both methods were similar, indicating a successful deployment, but it also revealed that microbial life was very patchy and related to the limited water availability, scarce nutrients and geochemistry of the soil.

"These results confirm a basic ecological rule that microbial life is patchy in Earth's most extreme habitats, which hints that past or present life on other planets may also exhibit patchiness," explain study co-authors Nathalie Cabrol and Kim Warren-Rhodes of The SETI Institute. "While this will make detection more challenging, our findings provide possible signposts to guide the exploration for life on Mars, demonstrating that it is possible to detect life with smart robotic search and sampling strategies."

Pointing highlights that future research includes drilling deeper to understand just how far down recoverable microbes occur.

"Mars missions hope to drill to approximately 2m and so having an Earth-based comparison will help identify potential problems and the interpretation of results once rovers are deployed there. Ecological studies that help us predict the habitable areas for microbial communities in Earth's most extreme environments will also be critical to finding life on other planets."

Quelle: AAAS

+++

FIT FOR MARS

Rovers are versatile explorers on the surface of other planets, but they do need some training before setting off. A model of Rosalind Franklin rover that will be sent to Mars in 2021 is scouting the Atacama Desert, in Chile, following commands from mission control in the United Kingdom, over 11 000 km away.

The ExoFiT field campaign simulates ExoMarsoperations in every key aspect. During the trial, the rover drove from its landing platform and targets sites of interest to sample rocks in the Mars-like landscapes of the Chilean desert.

ESA’s human and robotic exploration director, David Parker, explains “we call these tests ‘ExoFit’ - meaning ExoMars-like Field Testing. The results will help us prepare the real Rosalind Franklin rover for the challenge of safe operation far across the Solar System.”

The team behind the exercise, a mix of scientists and engineers, is simulating all the challenges of a real mission on the Red Planet, including communication delays, local weather conditions and tight deadlines.

“We make teleoperations as martian as possible,” explains Juan Delfa, ESA’s robotics engineer overseeing the activities.

“We are continuously working against the clock as you need to take into account signals from Mars take between 4 and 24 minutes to arrive at Earth while blasts of wind might cover the rover’s solar panels with dust, and that we only have a few hours to decide what the rover should do next,” adds Juan.

The campaign started on 18 February and will run until 1 March. This is the first time that ESA’s European Centre for Space Applications and Telecommunications (ECSAT), in Harwell, UK, is acting as a mission control.

With over 60 people from different space and scientific organisations involved, “it is all about getting the teams to practice with real mission issues. We are learning how to teleoperate a rover in the field and to make decisions in the most efficient way,” says Lester Waugh, ExoFiT mission manager from Airbus.

A rover on the field, scientists in the blind

The rover is equipped with a set of cameras and proxy instruments, such as a radar, a spectrometer and a drill, to replicate martian operations.

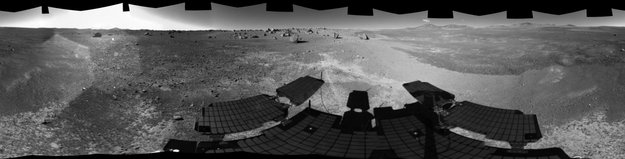

As it departed from the ‘landing site’ in a remote barren area, the first thing this prototype of ExoMars did was share a panoramic image and its location coordinates with mission control.

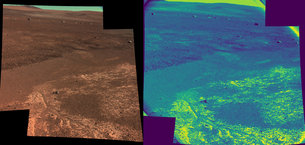

Scientists in the UK must take decisions on the next steps with the little information they have – a combination of the data transmitted by the rover and satellite images of the terrain.

“We only see what the rover sends us and we cannot rely on any other real-time information,” explains lead mission scientist Matt Balme, a planetary geologist from The Open University.

On every martian day, known as sol in the planetary jargon, scientists analyse the data they receive and establish a whole plan for the next day in just a few hours. “It is a logistical challenge, and the planning cycle is quite stressful,” says Matt.

The ExoFiT teams in the UK set the exploration path and activities for the rover, which travels at a speed of two centimeters per second avoiding rocks and overcoming slopes.

Drilling into ancient rocks is an important part of the trial. “Just like we would do on Mars, we want to understand the geological history of the area and look for signs of life,” says Matt.

ExoFiT stands for ExoMars-like Field Testing, and it is an essential step to improving European robotic operations not only for ExoMars, but also for future missions aiming to return soil from the Red Planet, such as the Mars Sample Return mission.