1.02.2019

The composition of the universe—the elements that are the building blocks for every bit of matter—is ever-changing and ever-evolving, thanks to the lives and deaths of stars.

An outline of how those elements form as stars grow and explode and fade and merge is detailed in a review article published Jan. 31 in the journal Science.

“The universe went through some very interesting changes, where all of a sudden the periodic table—the total number of elements in the universe—changed a lot,” said Jennifer Johnson, a professor of astronomy at The Ohio State University and the article’s author.

“For 100 million years after the Big Bang, there was nothing but hydrogen, helium and lithium. And then we started to get carbon and oxygen and really important things. And now, we’re kind of in the glory days of populating the periodic table.”

The periodic table has helped humans understand the elements of the universe since the 1860s, when a Russian chemist, Dmitri Mendeleev, recognized that certain elements behaved the same way chemically, and organized them into a chart—the periodic table.

It is chemistry’s way of organizing elements, helping scientists from elementary school to the world’s best laboratories understand how materials around the universe come together.

But, as scientists have long known, the periodic table is just made of stardust: Most elements on the periodic table, from the lightest hydrogen to heavier elements like lawrencium, started in stars.

The table has grown as new elements have been discovered—or in cases of synthetic elements, have been created in laboratories around the world—but the basics of Mendeleev’s understanding of atomic weight and the building blocks of the universe have held true.

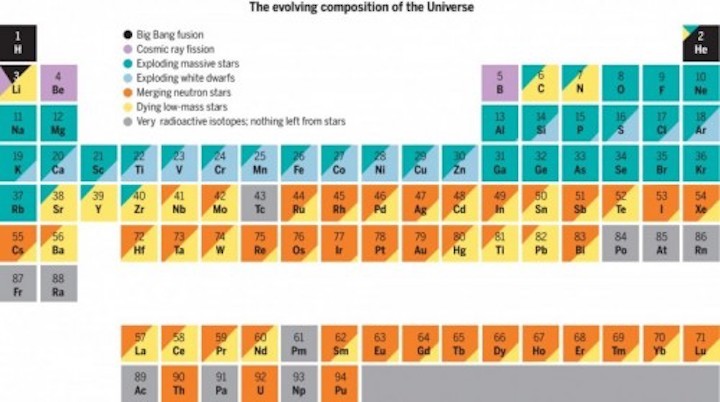

The elements of the periodic table are created through the lives and deaths of stars. (Reprinted with permission from AAAS.)

Nucleosynthesis—the process of creating a new element—began with the Big Bang, about 13.7 billion years ago. The lightest elements in the universe, hydrogen and helium, were also the first, results of the Big Bang. But heavier elements—just about every other element on the periodic table—are largely the products of the lives and deaths of stars.

Johnson said that high-mass stars, including some in the constellation Orion, about 1,300 light years from Earth, fuse elements much faster than low-mass stars. These grandiose stars fuse hydrogen and helium into carbon, and turn carbon into magnesium, sodium and neon. High-mass stars die by exploding into supernovae, releasing elements—from oxygen to silicon to selenium—into space around them.

Smaller, low-mass stars—stars about the size of our own Sun—fuse hydrogen and helium together in their cores. That helium then fuses into carbon. When the small star dies, it leaves behind a white dwarf star. White dwarfs synthesize other elements when they merge and explode. An exploding white dwarf might send calcium or iron into the abyss surrounding it. Merging neutron stars might create rhodium or xenon. And because, like humans, stars live and die on different time scales—and because different elements are produced as a star goes through its life and death—the composition of elements in the universe also changes over time.

“One of the things I like most about this is how it takes several different processes for stars to make elements and these processes are interestingly distributed across the periodic table,” Johnson said. “When we think of all the elements in the universe, it is interesting to think about how many stars gave their lives—and not just high-mass stars blowing up into supernovae. It’s also some stars like our Sun, and older stars. It takes a nice little range of stars to give us elements.”

We’re kind of in the glory days of populating the periodic table.