10.01.2019

Credit: NASA Johnson

When Neil Armstrong was preparing to leave the moon nearly 50 years ago, he allegedly thought the box holding the team's rock samples looked a little empty. So he shoveled in some soil to top it off.

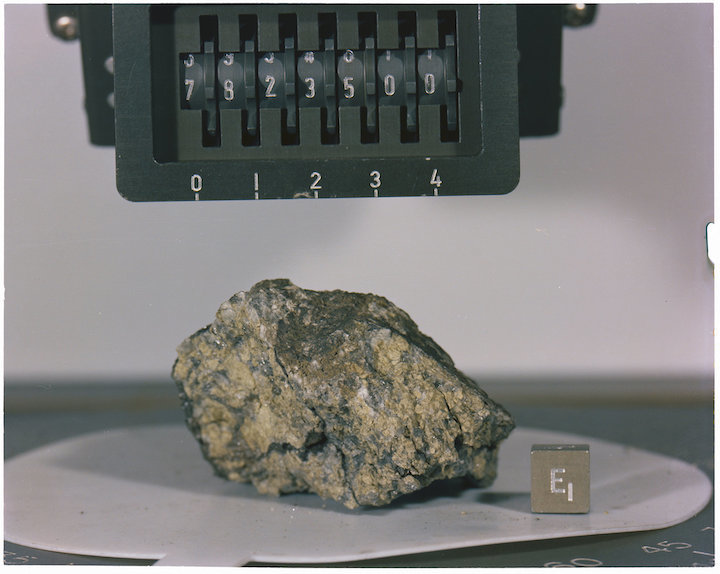

The consequences of that spontaneous decision continue today. All that soil, along with the rocks it joined, became humanity's first of six installments of lunar samples carried home by the Apollo program. Unlike your vacation souvenirs, the Apollo lunar samples are still being studied, even five decades after astronauts ferried them home. They're the only planetary samples that have been gathered by humans, which makes them a uniquely valuable collection of material.

"It's just easier with humans," Ryan Zeigler, Apollo sample curator and manager of NASA's Astromaterials Acquisition and Curation Office, told Space.com last month at the annual conference of the American Geophysical Union. "Humans are the most capable tool we have. It sounds like a cliché, but it'll take them a year to design a rover that can do one thing. A human can do the same thing just because they can."

Credit: David Scott/NASA

Humans, unlike robots, can easily be equipped with a wider variety of tools, and they can make their own decisions, like shoveling 13 lbs. (6 kilograms) of extra soil into a sample bin. All told, the lunar-landing missions brought 842 lbs. (382 kg) of material back to Earth; for eight years it has been Zeigler's job to look after the samples NASA has held onto for scientific research.

"I think people in general think, 'We've had the Apollo samples for a long time, so why are we still studying them?'" Zeigler said. "There's real, new work that's being done on them that's not just repeating what was done decades ago."

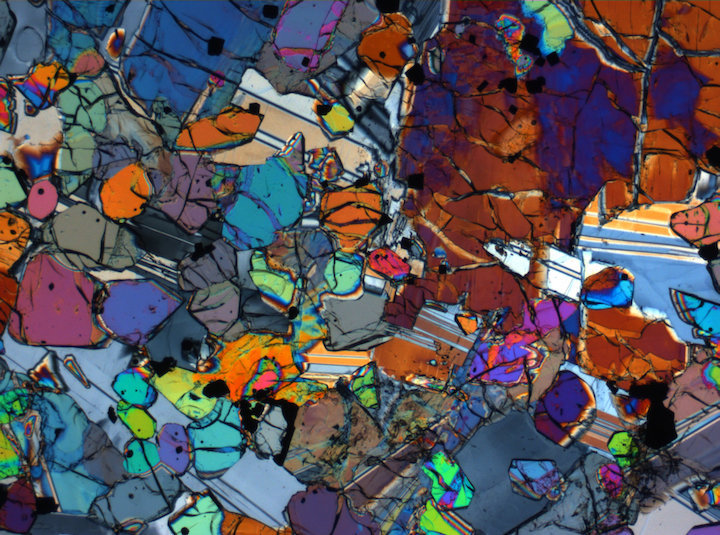

That's the real benefit of bringing samples back to Earth, after all — rather than simply having the data produced by an orbiter or lander at a particular time, scientists can over time apply new technology to answer new questions.

Scientists can enlist plenty of other new technology as well, like an X-ray CT scanner NASA recently acquired. By identifying structures within samples, the instrument can guide where scientists cut rocks, preventing them from destroying the very structures they'd like to study. The idea itself isn't new, but the specific instrument is better tailored to the job than its predecessors.

"People have been doing it for rock studies for going on a decade or 15 years," Zeigler said. "They used to struggle using medical CT scanners to try to scan rocks, and that didn't work well."

Credit: NASA

But it's not just new technology that is opening new opportunities for lunar sample science, Zeigler added. NASA's current focus on returning humans to the moon initiated by Space Policy Directive 1 in December 2017 has lent extra enthusiasm to collection analysis, he said.

And soon, scientists will have more samples to work with, since NASA has decided to open Apollo samples that haven't been touched since the end of the program. "We've been saving them for 50 years to make sure we had better instrumentation so that we could answer questions that we couldn't have addressed in 1972 when they were sealed," Zeigler said.

Credit: NASA

Those samples were vacuum sealed during their collection on the moon and again on Earth, but scientists aren't sure yet how well those seals have held up over the decades. If the seals have survived, these samples should still hold volatiles, including compounds like water, hydrogen and methane, which are deeply relevant to human exploration.

"There's stuff that they might get out of those samples that might actually help with future exploration of the moon," Zeigler said.

Quelle: SC