7.12.2018

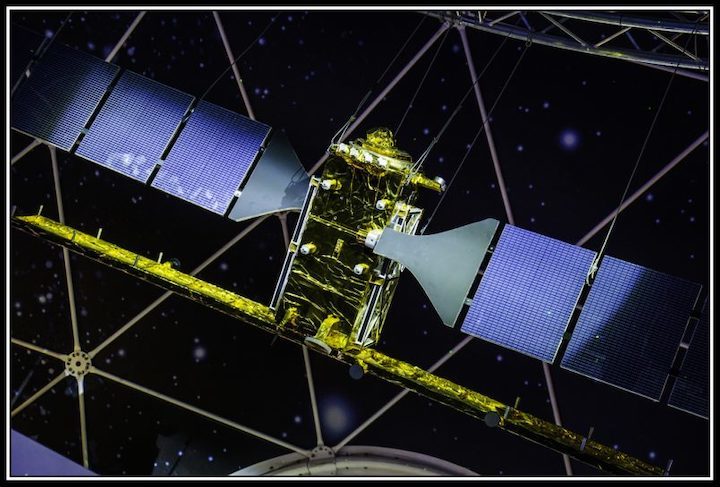

Last month, Ethiopia officially announced plans to launch its first earth observatory satellite, with China footing 75% of the $8 million bill and providing technical assistance. Such comprehensive assistance is of course welcome news for Ethiopia’s burgeoning space program, but it’s an open question to what extent the government is aware that Chinese finance comes with its own hidden costs.

Ethiopia’s space ambitions started to pick up in 2016 with the establishment of the Ethiopian Space Science and Technology Institute (ESSTI). A year later, the government outlined its intentions to launch a satellite within three to five years for the purpose of improving Ethiopia’s weather monitoring capabilities. Largely due to the falling costs of satellite technology, an increasing number of countries are turning their gaze skyward. In Africa, countries including Egypt, Kenya, Nigeria, Morocco, and South Africa have been participating in or leading their own space programs, while the African Union has also introduced an African space policy. As climate change makes earth observation all the more crucial, and as the technology becomes more accessible, sub-Saharan demand for satellite capacity is expected to double over the next five years.

Ethiopia’s planned satellite launch is clearly indicative of a wider trend towards embracing space technology on the African continent, but China’s participation in the Ethiopian program is representative of an arguably more significant development. Indeed, Beijing is an increasingly important, if not critical, partner for a growing number of African nations. Politically and economically, China’s involvement in the continent has deepened significantly over the past decade, with Beijing doubling its financial commitment at the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) in 2009, again in 2012, and then tripling its FOCAC commitment to $60 billion in 2015. Incredibly, China is now the single largest bilateral financier of infrastructure in Africa.

Building infrastructure is an important part of China’s engagement with Africa, and these efforts fall under the rubric of Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – an ambitious global campaign to construct transport and other projects with the use of Chinese finance and companies. But the Belt and Road isn’t limited to traditional hard infrastructure like railroads and power stations; China also wants to play a leading role in developing the digital and space capabilities of partner countries. As such, the “digital silk road” has become a hotly promoted aspect of the BRI, and space has been touted as the latest domain to be included in BRI’s expansive geographical scope.

Of course, vast swaths of sub-Saharan Africa are in desperate need of new infrastructure and the finance required to build it, and in this sense, Chinese loans are filling a gaping void. But Beijing’s infrastructure finance does not come without strings attached, and there are significant downsides to the growing role of China on the continent.

To begin with, the most obvious problem with the BRI in Africa is the burden Chinese loans place on many countries already at high risk of debt distress. Beijing does not build railroads and ports for free, even when the work is being carried out by Chinese companies – instead, African nations must take out loans (often concessional but not interest-free) from Chinese banks to pay these Chinese contractors. The US is particularly worried about Chinese lending habits, not only because they put smaller countries at risk of financial instability, but also because China has a record of leveraging the debt it holds so as to secure resources and strategic assets.

Additionally, the digital silk road has its own particular set of risks associated with it. Even Ethiopia’s supposedly weather-monitoring satellite could easily be used for military or surveillance purposes, and China has already proven itself willing to abuse its role in infrastructure construction for the sake of intelligence operations. For instance, earlier this year it was revealed that China had allegedly bugged the building it had given the African Union for its headquarters, providing Chinese intelligence with unfettered access to data.

Beijing may claim to be a benign power with no military or security ambitions in Africa, but the facts suggest otherwise. “Non-interference” has been a guiding principle of China’s foreign policy for decades, but there is growing gap between rhetoric and reality when it comes to China’s security footprint abroad. This security footprint is particularly deep in Africa, where China has performed its first military evacuations, staged large-scale anti-piracy missions, and most significantly, opened its first overseas permanent military base, in Djibouti.

In recent years, Beijing has poured billions into Djibouti, and the tiny African nation has racked up a GDP-sized bill to China that it can’t hope to pay off. In Washington, experts fear the strategic implications of this debt. Earlier this year, Djibouti nationalized a privately operated container terminal, prompting concerns that the port is destined as a gift for the country’s Chinese creditors. This is of particular concern to the US as they operate their own base, Camp Lemonnier, only a few kilometers away from the Chinese facility. If Beijing were to tighten its stranglehold over Djibouti, it would have significant consequences for US operations in Africa.

When Beijing first began negotiating its base in Djibouti, it described it as a “logistics facility”. Not long after, Chinese troops were conducting live fire drills, firmly discrediting any defense of the base as a non-military facility. Now, Chinese personnel have been allegedly targeting US fighter pilots with military grade lasers. Time and time again, Beijing has attempted to mask strategic intention with peaceful rhetoric. Escalation is the name of the game, with military ambitions revealing themselves overtime as China’s economic leverage grows. That is why Beijing’s involvement in satellite programs, which can so easily be operationalized for military purposes, is so concerning.

Of course, no one is doubting that countries like Ethiopia benefit from infrastructure funds made available by China, but it should not be forgotten that these funds come at significant costs. Unsustainable debt risks instability or outright ownership and violation of sovereignty. When assets like satellites are involved, China’s leverage is of particular cause for concern. China’s security footprint in Africa is growing, and Beijing has proven its intentions to maintain an active military presence on the continent. Intimate exposure to sensitive projects like national space programs could prove too tempting an opportunity for Chinese intelligence to pass up.

Quelle: Africa Times