4.12.2018

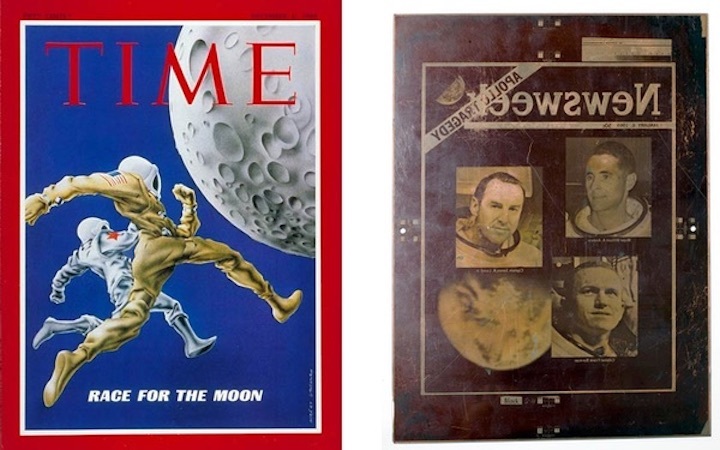

Time Magazine cover from early December and the unused printing plate for the early January edition of Newsweek in the event that the Apollo 8 mission failed and the astronauts died.

In early December 1968, Time magazine ran a cover story titled “Race for the Moon” featuring an astronaut and cosmonaut sprinting towards the Moon. Just a few weeks later, Newsweekmagazine featured a cover story about the Apollo 8 mission titled “Apollo Triumph.” But the editors had also created an alternative cover with the words “Apollo Tragedy” that, fortunately, was never used. What the two major news magazines reflected was both the belief that the United States and Russia were neck and neck in competition, and that the Apollo 8 mission was highly risky and could end tragically.

| What the two major news magazines reflected was both the belief that the United States and Russia were neck and neck in competition, and that the Apollo 8 mission was highly risky and could end tragically. |

This December marks the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 8 mission around the Moon, and that event has been commemorated in many ways the past few months. It was a courageous effort by the Apollo 8 astronauts, but also a bold and risky decision by NASA officials to send them on that journey. Over the decades, many historians have focused on the decision to send Apollo 8 around the Moon. The two major drivers were the availability of the Lunar Module—which had fallen behind schedule—and unmanned Soviet space missions that were clearly tests of their circumlunar spacecraft, called Zond.

The Russians are coming…

Apollo 8 commander Frank Borman in early August 1968 received orders to go to Houston immediately. “I flew a T-38 to Houston and walked into Deke’s office. I knew something was up when he asked me to close the door,” Borman wrote in his 1988 autobiography.

“We just got word from the CIA that the Russians are planning a lunar fly-by before the end of the year,” Deke Slayton told him. “We want to change Apollo 8 from an earth orbital to a lunar orbital flight. I know that doesn’t give us much time, so I have to ask you: Do you want to do it or not?”

Yes, Borman replied.

“I found out later that the Soviets were a hell of a lot closer to a manned lunar mission than we would have liked. Only about a month after I talked to Slayton, the Russians sent an unmanned spacecraft, Zond 5, into lunar orbit and returned it safely to earth.”

In the 1960s the CIA, the NSA, and other intelligence agencies were closely monitoring the Soviet space program, trying to discern what they were doing. A declassified CIA memo from October 1968 reported on the activities of the CIA’s Foreign Missile and Space Analysis Center, FMSAC, pronounced “foomsac” in the intelligence community at the time. FMSAC was established in late 1963 to give the CIA the ability to perform technical analyses of foreign—primarily Soviet—missiles and spacecraft. FMSAC became very good at trajectory analysis, taking radar and other data on the flights of foreign missiles and rockets collected from ground stations and determining the capabilities of those rockets and missiles based upon their flight paths.

The declassified CIA memo is a general account of FMSAC’s activities over the previous year. It stated:

“In the space area, FMSAC has the exclusive lead over all elements of the intelligence community and on an almost daily basis provides direct intelligence support, including many personal briefings, to the senior officials of NASA, the National Aeronautics and Space Council and the Presidential Science Advisory Council.”

Among the Center’s accomplishments in 1968, Carl Duckett, the CIA’s Deputy Director for Science and Technology wrote:

“The likelihood that the U.S. will conduct a manned circumlunar flight with the Apollo-8 vehicle in December is a result of the direct intelligence support that FMSAC has provided to NASA on present and future Soviet plans in space.”

The spooks are watching

The best and most comprehensive historical account of the Apollo 8 lunar decision is contained in Charles Murray and Catherine Bly Cox’s 1989 book Apollo: the Race to the Moon. Murray and Cox devoted ten pages to the subject. They clearly stated that the decision to send Apollo 8 on a circumlunar mission was overwhelmingly determined by Apollo’s aggressive schedule and not Cold War competition. In those ten pages they did not mention the Soviet lunar activities.

| None of the official NASA records on this subject, or George Low’s diary, mention Soviet plans to conduct a circumlunar flight. |

Apollo officials started initial discussion of a circumlunar mission in spring 1968, primarily as a theoretical option, although a circumlunar mission without a lunar module had first been mentioned a year earlier as a way to make up time lost due to the Apollo 1 fire. The proposed mission was seriously evaluated by NASA officials in early August when it became clear that the Lunar Module originally scheduled for the upcoming mission was delayed. George Low, the director of the Apollo Spacecraft Program Office, explained that the Lunar Module “had what we call ‘first ship problems.’ It always takes the first ship longer to get through.” The Lunar Module would not be ready until March 1969.

In order to stay on schedule for testing both the Saturn V and the Command and Service Modules, NASA would have to launch a mission into high Earth orbit without the Lunar Module. George Low argued that in place of a high Earth orbit mission, NASA should instead fly a circumlunar mission. During several days in August, Low discussed this with various senior officials before taking it directly to NASA Administrator James Webb. Webb tentatively agreed to the plan, but withheld final approval until after Apollo 7 flew in October.

It was a gutsy decision for NASA officials to make.

None of the official NASA records on this subject, or George Low’s diary, mention Soviet plans to conduct a circumlunar flight. Low and other NASA officials were certainly aware of Soviet circumlunar efforts, but there are no official NASA records indicating that it was even considered in their decision-making. Although intelligence information on Soviet activities was classified at the time and would not have been mentioned in unclassified NASA records, the Soviet activities were also mentioned in public news sources, and therefore NASA officials could have at least referred to those accounts.

The CIA and the National Security Agency had both been monitoring Soviet space activities throughout the year. In April 1968 the CIA produced a “Memorandum to Holders” supplement to an earlier 1967 National Intelligence Estimate (NIE) on the Soviet space program. Although the CIA was producing NIEs on the Soviet space program every two years, enough had happened in the past year that they wanted to update recipients of their 1967 report. The Memorandum to Holders included a table of space launches that mentioned the March 1968 Soviet Zond 4 mission, which it designated a “Circumlunar Simulation.” According to the memo, the mission was a “partial success,” which was explained in a footnote as “all phases of this mission appeared successful except reentry/recovery.” Zond 4’s mission had also been covered in the press at the time, so it certainly would have been well-known even to NASA officials without access to classified intelligence reports.

But the April memo also specifically addressed Soviet circumlunar plans: “The Soviets will probably attempt a manned circumlunar flight both as a preliminary to a manned lunar landing and as an attempt to lessen the psychological impact of the Apollo program. In NIE 11-1-67, we estimated that the Soviets would attempt such a mission in the first half of 1968 or the first half of 1969 (or even as early as late 1967 for an anniversary spectacular). The failure of the unmanned circumlunar test in November 1967 leads us now to estimate that a manned attempt is unlikely before the last half of 1968, with 1969 being more likely. The Soviets soon will probably attempt another unmanned circumlunar flight.” An accompanying bar chart made the same point, with the last six months of 1968 shaded as “earliest possible” for a manned circumlunar flight, and all of 1969 shaded as “more likely.”

| Even if the CIA did provide extensive information to NASA about Soviet circumlunar plans, that does not necessarily mean that, as the memo indicates, the NASA decision was a “result” of CIA information. |

It is possible the CIA obtained new information after producing that April memo that led their experts to believe that a Soviet manned circumlunar flight was more likely in early 1969 or even late 1968 than they had assumed in April, increasing the pressure on NASA to do something. Perhaps in June or July the CIA somehow learned about the upcoming Zond 5 flight and informed NASA. The Zond 5 flight took place in September, after the Apollo 8 decision was essentially made. It is also possible that FMSAC was exaggerating its role in NASA’s circumlunar decision, or at least assuming that FMSAC had played a greater role in convincing NASA’s leadership to attempt the Apollo 8 mission around the Moon than it actually had. Without more details, it is still not possible to know.

Even if the CIA did provide extensive information to NASA about Soviet circumlunar plans, that does not necessarily mean that, as the memo indicates, the NASA decision was a “result” of CIA information. Only the NASA officials who made the Apollo 8 decision knew what factors influenced them most. That was primarily George Low, whose records point to the Apollo schedule being the primary influence.

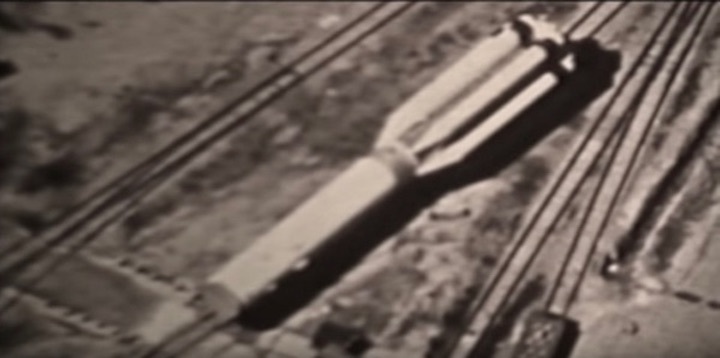

KH-8 GAMBIT-3 reconnaissance satellite image of a Soviet Proton rocket near its launch site at Baikonur (then known as Tyura-Tam to the CIA), date unknown. This image is taken from a declassified National Reconnaissance Office video and is badly degraded. But the close-up image still indicates that American reconnaissance satellites were producing detailed photographs of Soviet space hardware that were used in assessing Soviet capabilities to send humans around the Moon and to the lunar surface. (credit: NRO)

Photos and signals

American intelligence assets focused on the Soviet Union were getting increasingly capable. CIA and NSA listening posts around the world were gathering up signals from Soviet spacecraft as well as monitoring the movements of ships used to track spacecraft and recover them from the water. Much of the information on this intelligence remains classified, although it is slowly coming out. (See “A taste of Armageddon (part 1),” The Space Review, January 3, 2017, and “A taste of Armageddon (part 2),” The Space Review, January 9, 2017.)

In July 1966, the Air Force launched the first of the National Reconnaissance Office’s KH-8 GAMBIT-3 reconnaissance satellites, and by early November 1968, 17 of them had been launched, with one failing to reach orbit. The GAMBIT’s powerful camera could reveal amazing detail about Soviet submarines, missile silos, and rockets. A GAMBIT photo, recently revealed in a new video, shows a Soviet Proton rocket—the same rocket used to launch Zond spacecraft around the Moon—lying on its side near the launch site. The rocket lacks a spacecraft on its nose. The date of the photo is unknown, and it has been degraded by multiple reproductions, but the image provides a stark indication of just how good the intelligence information on Soviet space capabilities had become by the late 1960s. Photos like that, shown to a select group of NASA officials, would have provided useful intelligence data on Soviet capabilities, although not necessarily their intentions.

Certainly the race to the Moon with the Soviets established the larger context in which all NASA decisions were made. The preponderance of evidence still supports the conclusion that it was the Apollo schedule that drove the decision, not specific Soviet actions. But the document from the CIA’s Foreign Missile and Space Analysis Center now gives historians another line of investigation, and it proves something that historians forget at their peril: that new information may be awaiting discovery, sometimes filed away in an archive for decades until somebody who is interested in that subject finds it and places it in proper historical context. And an intriguing set of questions remain unanswered: just what did the CIA know about the Soviet Zond flight plans, when did they know it, what did they tell NASA, and when?

Quelle: The Space Review