21.11.2018

Mars revisited: NASA spacecraft days away from risky landing

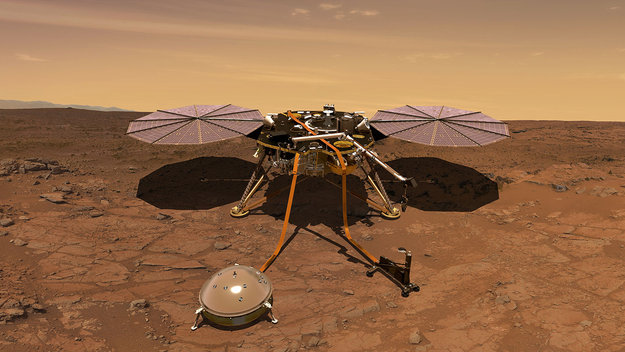

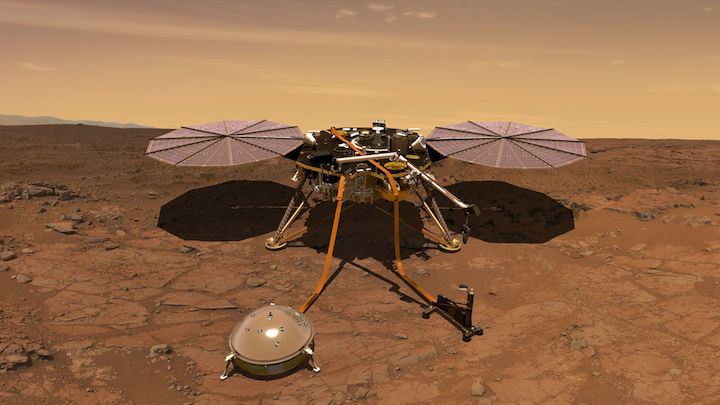

Mars is about to get its first U.S. visitor in years: a three-legged, one-armed geologist to dig deep and listen for quakes.

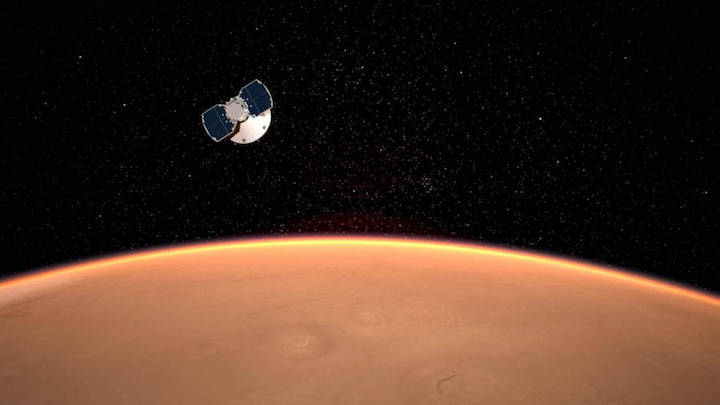

NASA's InSight makes its grand entrance through the rose-tinted Martian skies on Monday, after a six-month, 300 million-mile (480 million-kilometer) journey. It will be the first American spacecraft to land since the Curiosity rover in 2012 and the first dedicated to exploring underground.

NASA is going with a tried-and-true method to get this mechanical miner to the surface of the red planet. Engine firings will slow its final descent and the spacecraft will plop down on its rigid legs, mimicking the landings of earlier successful missions.

That's where old school ends on this $1 billion U.S.-European effort .

Once flight controllers in California determine the coast is clear at the landing site — fairly flat and rock free — InSight's 6-foot (1.8-meter) arm will remove the two main science experiments from the lander's deck and place them directly on the Martian surface.

No spacecraft has attempted anything like that before.

The firsts don't stop there.

One experiment will attempt to penetrate 16 feet (5 meters) into Mars, using a self-hammering nail with heat sensors to gauge the planet's internal temperature. That would shatter the out-of-this-world depth record of 8 feet (2 ½ meters) drilled by the Apollo moonwalkers nearly a half-century ago for lunar heat measurements.

The astronauts also left behind instruments to measure moonquakes. InSight carries the first seismometers to monitor for marsquakes — if they exist. Yet another experiment will calculate Mars' wobble, providing clues about the planet's core.

It won't be looking for signs of life, past or present. No life detectors are on board.

The spacecraft is like a self-sufficient robot, said lead scientist Bruce Banerdt of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

"It's got its own brain. It's got an arm that can manipulate things around. It can listen with its seismometer. It can feel things with the pressure sensors and the temperature sensors. It pulls its own power out of the sun," he said.

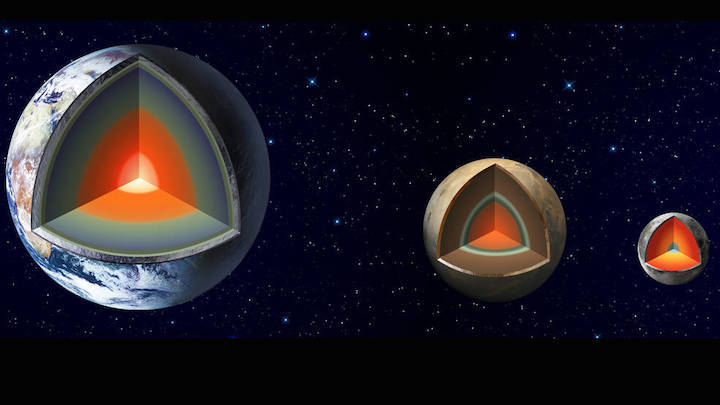

By scoping out the insides of Mars, scientists could learn how our neighbor — and other rocky worlds, including the Earth and moon — formed and transformed over billions of years. Mars is much less geologically active than Earth, and so its interior is closer to being in its original state — a tantalizing time capsule.

InSight stands to "revolutionize the way we think about the inside of the planet," said NASA's science mission chief, Thomas Zurbuchen.

But first, the 800-pound (360-kilogram) vehicle needs to get safely to the Martian surface. This time, there won't be a ball bouncing down with the spacecraft tucked inside, like there were for the Spirit and Opportunity rovers in 2004. And there won't be a sky crane to lower the lander like there was for the six-wheeled Curiosity during its dramatic "seven minutes of terror."

"That was crazy," acknowledged InSight's project manager, Tom Hoffman. But he noted, "Any time you're trying to land on Mars, it's crazy, frankly. I don't think there's a sane way to do it."

No matter how it's done, getting to Mars and landing there is hard — and unforgiving.

Earth's success rate at Mars is a mere 40 percent. That includes planetary flybys dating back to the early 1960s, as well as orbiters and landers.

While it's had its share of flops, the U.S. has by far the best track record. No one else has managed to land and operate a spacecraft on Mars. Two years ago, a European lander came in so fast, its descent system askew, that it carved out a crater on impact.

This time, NASA is borrowing a page from the 1976 twin Vikings and the 2008 Phoenix, which also were stationary and three-legged.

"But you never know what Mars is going to do," Hoffman said. "Just because we've done it before doesn't mean we're not nervous and excited about doing it again."

Wind gusts could send the spacecraft into a dangerous tumble during descent, or the parachute could get tangled. A dust storm like the one that enveloped Mars this past summer could hamper InSight's ability to generate solar power. A leg could buckle. The arm could jam.

The tensest time for flight controllers in Pasadena, California: the six minutes from the time the spacecraft hits Mars' atmosphere and touchdown. They'll have jars of peanuts on hand — a good-luck tradition dating back to 1964's successful Ranger 7 moon mission.

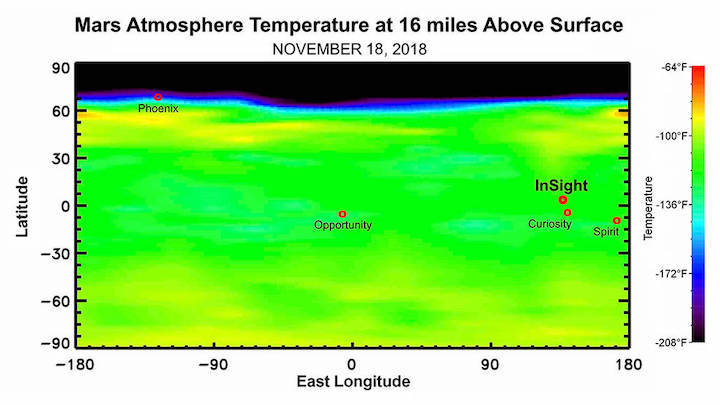

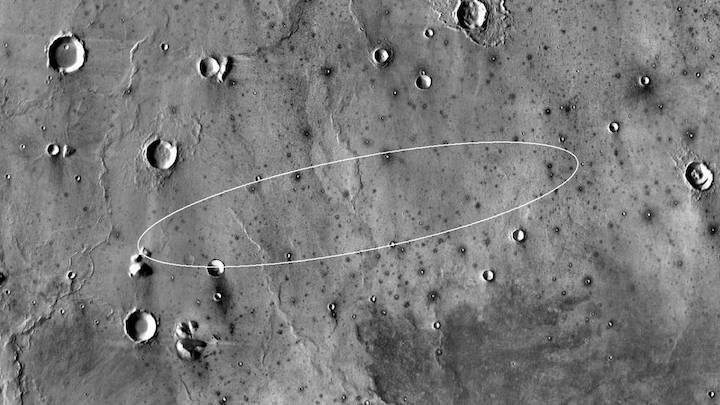

InSight will enter Mars' atmosphere at a supersonic 12,300 mph (19,800 kph), relying on its white nylon parachute and a series of engine firings to slow down enough for a soft upright landing on Mars' Elysium Planitia, a sizable equatorial plain.

Hoffman hopes it's "like a Walmart parking lot in Kansas."

The flatter the better so the lander doesn't tip over, ending the mission, and so the robotic arm can set the science instruments down.

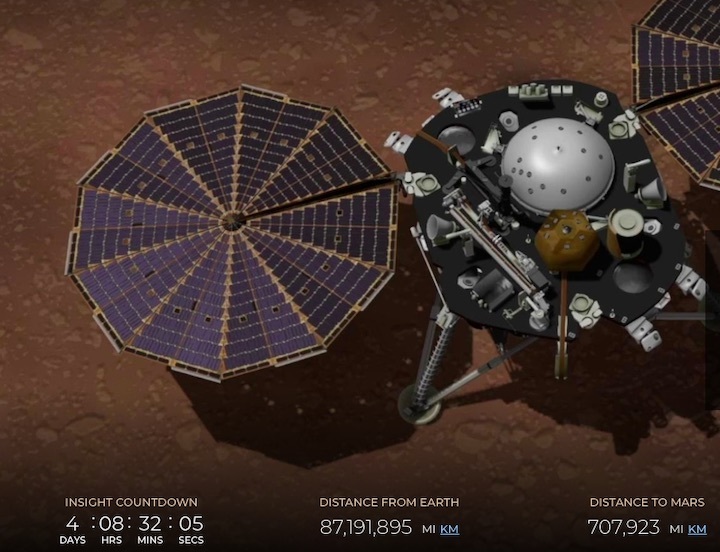

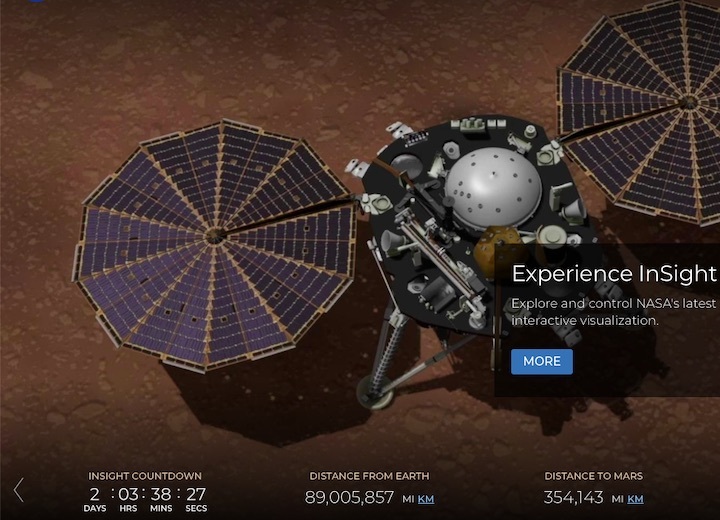

InSight — short for Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport — will rest close to the ground, its top deck barely a yard, or meter, above the surface. Once its twin circular solar panels open, the lander will occupy the space of a large car.

If NASA gets lucky, a pair of briefcase-size satellites trailing InSight since their joint May liftoff could provide near-live updates during the lander's descent. There's an eight-minute lag in communications between Earth and Mars.

The experimental CubeSats, dubbed WALL-E and EVE from the 2008 animated movie, will zoom past Mars and remain in perpetual orbit around the sun, their technology demonstration complete.

If WALL-E and EVE are mute, landing news will come from NASA orbiters at Mars, just not as quickly.

The first pictures of the landing site should start flowing shortly after touchdown. It will be at least 10 weeks before the science instruments are deployed. Add another several weeks for the heat probe to bury into Mars.

The mission is designed to last one full Martian year, the equivalent of two Earth years.

With landing day so close to Thanksgiving, many of the flight controllers will be eating turkey at their desks on the holiday.

Hoffman expects his team will wait until Monday to give full and proper thanks.

Quelle: abcNews

---

Update: 22.11.2018

.

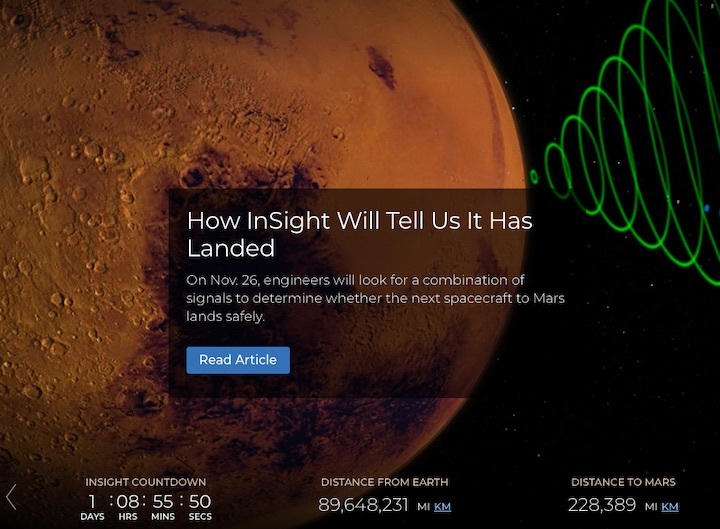

NASA InSight Team on Course for Mars Touchdown

NASA's Mars Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport (InSight) spacecraft is on track for a soft touchdown on the surface of the Red Planet on Nov. 26, the Monday after Thanksgiving. But it's not going to be a relaxing weekend of turkey leftovers, football and shopping for the InSight mission team. Engineers will be keeping a close eye on the stream of data indicating InSight's health and trajectory, and monitoring Martian weather reports to figure out if the team needs to make any final adjustments in preparation for landing, only five days away.

"Landing on Mars is hard. It takes skill, focus and years of preparation," said Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator for the Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington. "Keeping in mind our ambitious goal to eventually send humans to the surface of the Moon and then Mars, I know that our incredible science and engineering team — the only in the world to have successfully landed spacecraft on the Martian surface — will do everything they can to successfully land InSight on the Red Planet."

InSight, the first mission to study the deep interior of Mars, blasted off from Vandenberg Air Force Base in Central California on May 5, 2018. It has been an uneventful flight to Mars, and engineers like it that way. They will get plenty of excitement when InSight hits the top of the Martian atmosphere at 12,300 mph (19,800 kph) and slows down to 5 mph (8 kph) — about human jogging speed — before its three legs touch down on Martian soil. That extreme deceleration has to happen in just under seven minutes.

"There's a reason engineers call landing on Mars 'seven minutes of terror,'" said Rob Grover, InSight's entry, descent and landing (EDL) lead, based at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. "We can't joystick the landing, so we have to rely on the commands we pre-program into the spacecraft. We've spent years testing our plans, learning from other Mars landings and studying all the conditions Mars can throw at us. And we're going to stay vigilant till InSight settles into its home in the Elysium Planitia region."

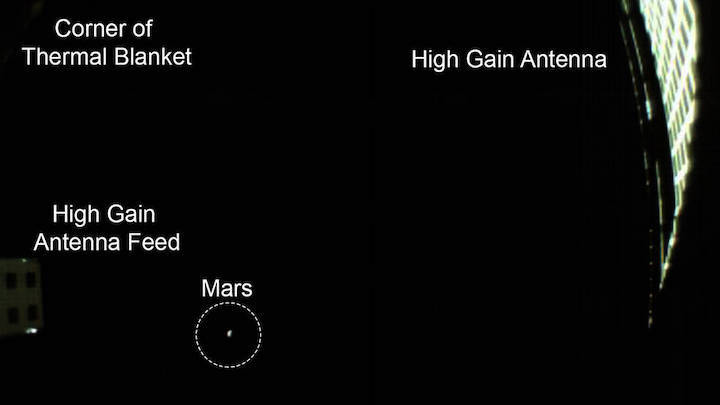

One way engineers may be able to confirm quickly what activities InSight has completed during those seven minutes of terror is if the experimental CubeSat mission known as Mars Cube One (MarCO) relays InSight data back to Earth in near-real time during their flyby on Nov. 26. The two MarCO spacecraft (A and B) are making good progress toward their rendezvous point, and their radios have already passed their first deep-space tests.

"Just by surviving the trip so far, the two MarCO satellites have made a giant leap for CubeSats," said Anne Marinan, a MarCO systems engineer based at JPL. "And now we are gearing up for the MarCOs' next test — serving as a possible model for a new kind of interplanetary communications relay."

If all goes well, the MarCOs may take a few seconds to receive and format the data before sending it back to Earth at the speed of light. This would mean engineers at JPL and another team at Lockheed Martin Space in Denver would be able to tell what the lander did during EDL approximately eight minutes after InSight completes its activities. Without MarCO, InSight's team would need to wait several hours for engineering data to return via the primary communications pathways — relays through NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and Mars Odyssey orbiter.

Once engineers know that the spacecraft has touched down safely in one of the several ways they have to confirm this milestone and that InSight's solar arrays have deployed properly, the team can settle into the careful, three-month-long process of deploying science instruments.

"Landing on Mars is exciting, but scientists are looking forward to the time after InSight lands," said Lori Glaze, acting director of the Planetary Science Division at NASA Headquarters. "Once InSight is settled on the Red Planet and its instruments are deployed, it will start collecting valuable information about the structure of Mars' deep interior — information that will help us understand the formation and evolution of all rocky planets, including the one we call home."

A number of European partners, including France's Centre National d'Études Spatiales (CNES) and the German Aerospace Center (DLR), are supporting the InSight mission. CNES and the Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris (IPGP) provided the Seismic Experiment for Interior Structure (SEIS) instrument, with significant contributions from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS) in Germany, the Swiss Institute of Technology (ETH) in Switzerland, Imperial College and Oxford University in the United Kingdom, and JPL. DLR provided the Heat Flow and Physical Properties Package (HP3) instrument, with significant contributions from the Space Research Center (CBK) of the Polish Academy of Sciences and Astronika in Poland. Spain’s Centro de Astrobiología (CAB) supplied the wind sensors.

ESA LENDS A HAND AT MARS

The Red Planet will receive its first new resident in six years on Monday when NASA’s InSight lander touches down, aiming to investigate the Martian interior. ESA ground stations and orbiters are playing a crucial role in helping the mission get to its destination and deliver its data back to Earth.

On 26 November, NASA’s robotic science lab will land on the dusty Martian surface around 20:00 UTC (21:00 CET).

Equipped with a suite of geological instruments, InSight will land at Elysium Planitia, a broad plain that has been called the “the biggest parking lot on Mars,” ready to spend two years measuring the planet’s internal heat, detect ‘marsquakes’ and more.

Because the lander will not rove across the Martian surface, it is vital that it lands in the right place the first time, where it will then release its solar panels and deploy its instruments, becoming the first mission to directly study another planet’s interior.

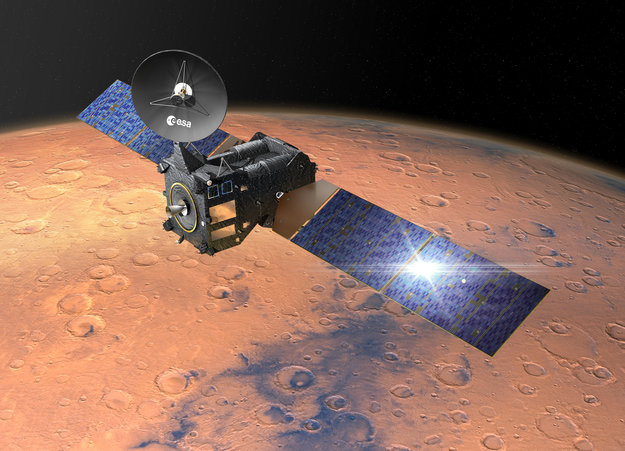

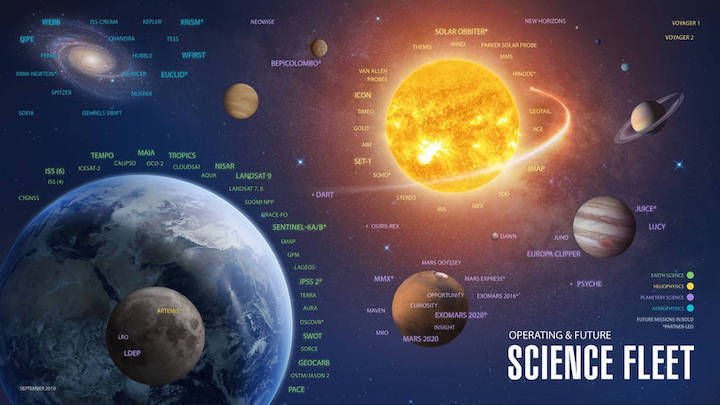

The European Space Agency is providing mission-critical support to InSight, using its deep-space ground tracking stations to communicate with the mission during the journey to Mars and, after landing, assigning the Agency’s ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) to help relay lander data back to Earth. Teams at ESA's ESOC mission control centre, in Darmstadt, Germany, are also on standby to relay instructions the other way, from Earth to the lander, if needed.

Getting by with a little help

Just five hours after InSight launched on 5 May 2018, ESA’s deep space ground station at New Norcia, in Western Australia, established contact and transmitted commands to InSight, the first time an ESA station transmitted commands to a NASA Mars mission in flight.

As InSight set out for Mars, ESA Estrack network stations provided additional communication slots, and served as back-up to NASA’s own Deep Space Network stations. The support is part of a long-standing cross-support agreement between the two agencies, in which one provides tracking station support to the other, boosting efficiency and redundancy for both.

On landing day, about 12 hours prior to the critical entry, descent and landing phase, ESA’s New Norcia station will again be in action, providing a ‘hot’ back-up communication link to InSight for the final ‘Target Correction Manoeuvre’ before it enters the Martian atmosphere.

Data from down below

Once on the surface, InSight will be located in view of a number of NASA and ESA orbiters, including ESA’s ExoMars TGO, which will provide routine data relay services to the lander throughout its life on Mars.

TGO, which is equipped with NASA-provided radio relay technology, will catch InSight data signals from the surface and relay them back to Earth, and slots for this important service are already planned starting the day after arrival, on 27 November.

While contingency data relay from NASA rovers and landers on the surface has been tested in the past using ESA’s Mars Express orbiter, use of TGO to provide routine data relay is a new aspect of cooperation at Mars for the two Agencies. TGO has also been providing regular data relay services for NASA's Curiosity and Opportunity rovers.

It is part of a larger cooperation at Mars that will see orbiters from both ESA and NASA relaying data from not only current and future NASA rovers and landers on the surface, but also from ESA’s ExoMars rover slated to land in 2021 and from the accompanying Russian surface platform.

“NASA's InSIght mission relies on crucial ESA support, and this is a highlight of the cooperation we have between the NASA and ESA Mars programmes,” says Paolo Ferri, Head of Mission Operations at ESA.

“In return, our ExoMars mission has received essential NASA support.”

“Mars is a rich scientific target, but an extremely challenging destination. Extending our long-standing technical, scientific and operational cooperation at the Red Planet is the only way to go.”

Watch the landing live on Monday from 19:00 UTC (20:00 CET), via NASA’s webcast.

Quelle: ESA

+++

Quelle: NASA

---

Update: 25.11.2018

.

NASA InSight Landing on Mars: Milestones

On Nov. 26, NASA's InSight spacecraft will blaze through the Martian atmosphere and attempt to set a lander gently on the surface of the Red Planet in less time than it takes to hard-boil an egg. InSight's entry, descent and landing (EDL) team, based at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, along with another part of the team at Lockheed Martin Space in Denver, have pre-programmed the spacecraft to perform a specific sequence of activities to make this possible.

The following is a list of expected milestones for the spacecraft, assuming all proceeds exactly as planned and engineers make no final changes the morning of landing day. Some milestones will be known quickly only if the experimental Mars Cube One (MarCO) spacecraft are providing a reliable communications relay from InSight back to Earth. The primary communications path for InSight engineering data during the landing process is through NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and Mars Odyssey. Those data are expected to become available several hours after landing.

If all goes well, MarCO may take a few seconds to receive and format the data before sending it back to Earth at the speed of light. The one-way time for a signal to reach Earth from Mars is eight minutes and seven seconds on Nov. 26. Times listed below are in Earth Receive Time, or the time JPL Mission Control may receive the signals relating to these activities.

- 11:40 a.m. PST (2:40 p.m. EST) — Separation from the cruise stage that carried the mission to Mars

- 11:41 a.m. PST (2:41 p.m. EST) — Turn to orient the spacecraft properly for atmospheric entry

- 11:47 a.m. PST (2:47 p.m. EST) — Atmospheric entry at about 12,300 mph (19,800 kph), beginning the entry, descent and landing phase

- 11:49 a.m. PST (2:49 p.m. EST) — Peak heating of the protective heat shield reaches about 2,700°F (about 1,500°C)

- 15 seconds later — Peak deceleration, with the intense heating causing possible temporary dropouts in radio signals

- 11:51 a.m. PST (2:51 p.m. EST) — Parachute deployment

- 15 seconds later — Separation from the heat shield

- 10 seconds later — Deployment of the lander's three legs

- 11:52 a.m. PST (2:52 p.m. EST) — Activation of the radar that will sense the distance to the ground

- 11:53 a.m. PST (2:53 p.m. EST) — First acquisition of the radar signal

- 20 seconds later — Separation from the back shell and parachute

- 0.5 second later — The retrorockets, or descent engines, begin firing

- 2.5 seconds later — Start of the "gravity turn" to get the lander into the proper orientation for landing

- 22 seconds later — InSight begins slowing to a constant velocity (from 17 mph to a constant 5 mph, or from 27 kph to 8 kph) for its soft landing

- 11:54 a.m. PST (2:54 p.m. EST) — Expected touchdown on the surface of Mars

- 12:01 p.m. PST (3:01 p.m. EST) — "Beep" from InSight's X-band radio directly back to Earth, indicating InSight is alive and functioning on the surface of Mars

- No earlier than 12:04 p.m. PST (3:04 p.m. EST), but possibly the next day — First image from InSight on the surface of Mars

- No earlier than 5:35 p.m. PST (8:35 p.m. EST) — Confirmation from InSight via NASA's Mars Odyssey orbiter that InSight's solar arrays have deployed

For the latest updates on InSight’s status, visit:

https://mars.nasa.gov/insight/timeline/landing/status/

The InSight press kit, with additional information about the mission time line, is available at:

https://go.nasa.gov/insight_pk

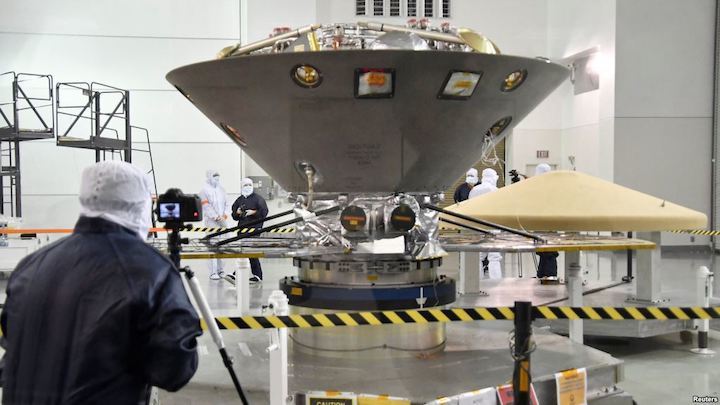

JPL manages InSight for NASA's Science Mission Directorate. InSight is part of NASA's Discovery Program, managed by the agency's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. Lockheed Martin Space in Denver built the InSight spacecraft, including its cruise stage and lander, and supports spacecraft operations for the mission.

A number of European partners, including France's Centre National d'Études Spatiales (CNES) and the German Aerospace Center (DLR), are supporting the InSight mission. CNES provided the Seismic Experiment for Interior Structure (SEIS) instrument, with significant contributions from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS) in Germany, the Swiss Institute of Technology (ETH) in Switzerland, Imperial College and Oxford University in the United Kingdom, and JPL. DLR provided the Heat Flow and Physical Properties Package (HP3) instrument, with significant contributions from the Space Research Center (CBK) of the Polish Academy of Sciences and Astronika in Poland. Spain’s Centro de Astrobiología (CAB) supplied the wind sensors.

Quelle: NASA

+++

InSight - Erkundung des Mars-Inneren

Mit der NASA-Landesonde InSight startete am 5. Mai 2018 eine Mission, die mit geophysikalischen Messungen direkt auf der Marsoberfläche den inneren Aufbau und den Wärmehaushalt des Planeten erkunden wird. Das Deutsche Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt (DLR) hat mit dem Instrument HP3 (Heat Flow and Physical Properties Package) ein Experiment zu dieser Mission beigesteuert. Am 26. November 2018 soll InSight nördlich des Äquators in der Ebene Elysium Planitia landen. Nach einer Testphase kann mit den Experimenten nach der Jahreswende 2018/19 begonnen werden. Die Missionsdauer ist zunächst auf ein Marsjahr festgelegt, das entspricht zwei Erdenjahren.

Es ist das erste Mal seit der Astronautenmission Apollo 17 im Jahr 1972, dass Wärmeflussmessungen mit einem Bohrmechanismus auf einem anderen Himmelskörper durchgeführt werden. Hauptziel des Experiments ist es, aus den Messungen des Wärmeflusses unter der Oberfläche den thermischen Zustand des Marsinneren ableiten zu können. Mit Hilfe der Daten können Modelle der Entwicklung des Mars, seiner chemischen Zusammensetzung und auch des inneren Aufbaus überprüft werden. Aus den Messungen auf dem Mars können auch Schlüsse für die frühe Entwicklung der Erde gezogen werden.

Vimeo-Video "Erkundung des Marsinneren - mit der DLR-Rammsonde HP3 (InSight-Mission/NASA)"

Quelle: DLR

+++

Update: 19.45 MEZ

.

NASA's InSight Is One Day Away from Mars

In just over 24 hours, NASA's InSight spacecraft will complete its seven-month journey to Mars. It will have cruised 301,223,981 miles (484,773,006 km) at a top speed of 6,200 mph (10,000 kph).

Engineers at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, which leads the mission, are preparing for the spacecraft to enter the Martian atmosphere, descend with a parachute and retrorockets, and touch down tomorrow at around noon PST (3 p.m. EST). InSight — which stands for Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport — will be the first mission to study the deep interior of Mars.

"We've studied Mars from orbit and from the surface since 1965, learning about its weather, atmosphere, geology and surface chemistry," said Lori Glaze, acting director of the Planetary Science Division in NASA's Science Mission Directorate. "Now we finally will explore inside Mars and deepen our understanding of our terrestrial neighbor as NASA prepares to send human explorers deeper into the solar system."

Before InSight enters the Martian atmosphere, there are a few final preparations to make. Engineers still need to conduct a last trajectory correction maneuver to steer the spacecraft toward its entry point over Mars. About two hours before hitting the atmosphere, the entry, descent and landing (EDL) team might also upload some final tweaks to the algorithm that guides the spacecraft safely to the surface.

These will be the last commands issued to InSight before it robotically guides itself the rest of the way. The EDL team worked for months beforehand to pre-program every stage of InSight's landing, making adjustments based on weather reports from NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

"While most of the country was enjoying Thanksgiving with their family and friends, the InSight team was busy making the final preparations for Monday's landing," said Tom Hoffman of JPL, InSight's project manager. "Landing on Mars is difficult and takes a lot of personal sacrifices, such as missing the traditional Thanksgiving, but making InSight successful is well worth the extraordinary effort."

Engineers will be huddled with scientists at JPL on Nov. 26, watching with nervous anticipation for signals that InSight successfully touched down.

"It's taken more than a decade to bring InSight from a concept to a spacecraft approaching Mars — and even longer since I was first inspired to try to undertake this kind of mission," said Bruce Banerdt of JPL, InSight's principal investigator. "But even after landing, we'll need to be patient for the science to begin."

It will take two to three months for InSight's robotic arm to set the mission's instruments on the surface. During that time, engineers will monitor the environment and photograph the terrain in front of the lander.

Back at JPL, the surface operations team will practice setting down the instruments. They'll use a working replica of InSight in an indoor "Mars sandbox," which will be sculpted to match the mission's actual landing site on Mars. The team will check to make sure the instruments can be deployed safely, even if there are rocks nearby or InSight lands at an angle.

Once the final position of each instrument is decided, it will take several weeks to carefully lift each one and calibrate their measurements. Then the science really gets underway.

Quelle: NASA

---

Update: 26.11.2018 / 7.30 MEZ

.

NASA’s ‘Cyber Monday’ Mars Landing to Deliver Science Firsts

In the News

NASA’s next mission to Mars, the InSight lander, is scheduled to land around noon PST on Monday, Nov. 26. So while some people are looking for Cyber Monday deals, scientists and engineers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory will be monitoring their screens for something else: signals from the spacecraft that it successfully touched down on the Red Planet.

Quelle: NASA