11.11.2018

Building a sustainable human presence on other worlds should be open to all. Comparing the journey to violent conquest doesn't help.

WHEN DISCUSSING SPACE exploration, people often invoke stories about the exploration of our own planet, like the European conquest and colonization of the Americas, or the march westward in the 1800s, when newly minted Americans believed it was their duty and destiny to expand across the continent.

But increasingly, government agencies, journalists, and the space community at large are recognizing that these narratives are born from racist, sexist ideologies that historically led to the subjugation and erasure of women and indigenous cultures, creating barriers that are still pervasive today.

To ensure that humanity’s future off-world is less harmful and open to all, many of the people involved are revising the problematic ways in which space exploration is framed. Numerous conversations are taking place about the importance of using inclusive language, with scholars focusing on decolonizing humanity’s next journeys into space, as well as science in general.

“Language matters, and it’s so important to be inclusive,” NASA astronaut Leland Melvin said recently during a talk at the University of Virginia.

Lucianne Walkowicz, an astronomer featured in National Geographic’s docudrama series Mars, spent the last year studying the ethics of Mars exploration as the Chair of Astrobiology at the U.S. Library of Congress. We recently spoke with Walkowicz to examine the problems associated with old-fashioned verbiage and to discuss some solutions. What follows is a record of that conversation, edited for length and clarity.

Why is it so crucial to consider the words we use when describing space exploration?

The language we use automatically frames how we envision the things we talk about. So, with space exploration, we have to consider how we are using that language, and what it carries from the history of exploration on Earth. Even if words like “colonization” have a different context off-world, on somewhere like Mars, it’s still not OK to use those narratives, because it erases the history of colonization here on our own planet. There’s this dual effect where it both frames our future and, in some sense, edits the past.

What are some of the problematic narratives the term “colonization” brings up?

One narrative that comes up a lot draws on the history of Europeans coming to the Americas. I’ve seen people talk about the arrival of the first European settlers as this romantic, heroic story of people making it in a harsh environment. But of course, there were already people here, in the Americas, when those historical events happened.

Furthermore, a lot of the Europeans’ ability to live throughout the Americas came at the cost of genocide for indigenous people. I think it’s not intuitive, particularly when we talk to white Americans, for example, to think of the history of Columbus’s journey as a story of genocide. But it’s important to realize that’s what it is.

A lot of those historical narratives are also bound up in the history of slavery, for example, so when we talk about how colonies in Virginia grew from being a few settlers to becoming tens of thousands of people, it’s also important to realize that roughly half of those people came against their own will, and many died along the way.

Has there been an instance of exploration in our history that hasn’t led to the subjugation of native cultures?

Who is “our”?

Planet Earth. Is there a narrative we can use that isn’t just trotting out Christopher Columbus and pretending like that’s a rosy picture?

That is really a question for a historian. I’m not a historian, but I’ll tell you that there probably isn’t a perfectly starched, unblemished narrative that you can draw from. It’s just that we need to not be carelessly using narratives that are still the source of harm to a lot of people.

In addition to “colonization” and its associated terms, what are some words you consider to be problematic when we talk about space exploration?

I think the other one is “settlement.” That comes up a lot and obviously has a lot of connotations for folks about conflict in the Middle East. I think that’s one that people often turn to when they mean “inhabitation” or “humans living off-world.”

Instead, I prefer using a couple of extra words, like “humans living on Mars,” or something that is maybe longer but more specific to what I mean. In the 1970s, Carl Sagan really liked the idea of space cities, because cities have lots of different kinds of people in them, generally speaking. But is a ship full of five people living on Mars actually a space city? Probably not. So, that isn’t necessarily the best solution, either.

What about terms like “manned” or “frontier?”

Yes, I do find “frontier” to be problematic. The implication is not exactly the same for somewhere like space as it is for here, but it similarly draws on the same kinds of narratives that are all based around European settlement. And often, if the word “frontier” comes up, it’s not wrong—until someone spells out the narrative of those brave explorers who went West in the early Americas.

“Manned?” I don’t understand why anyone is still using “manned.” How old is the NASA style guide that says not to use “manned?” It’s been around literally for years [since 2006, to be precise].

Yet it’s all over the place, and people will defend it.

It’s so lazy. Just think about it a little bit.

It seems like the language that we use when describing space exploration necessarily reflects both motivation and access to space. Do you think it’s possible for humans to progress in a way that will allow space travelers to better reflect humanity?

I think that one of the very first steps forward is to stop having our narratives about space only coming from people who are extremely privileged, which in this space means predominantly rich, white, male venture capitalists. That’s really who’s driving a lot of the narratives that are used, and why there’s not a lot of forethought or response to critiques about those frontier, colonialist narratives.

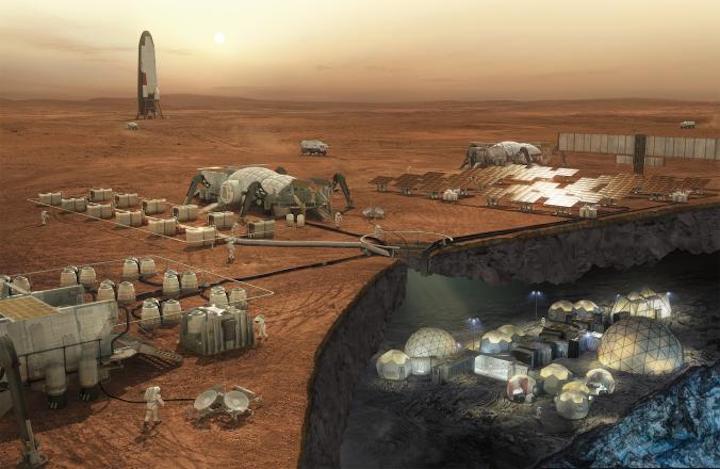

MARS EXPLORATION PICTURES

A self-portrait of the Mars rover Curiosity.

PHOTOGRAPH BY NASA, APThis enhanced color image shows several craters somewhere in the southern mid-latitudes of Mars. The bluish deposits are most likely iron-bearing minerals that have not been previously oxidized, or rusted.

PHOTOGRAPH BY NASA, JPL, UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONAThe impact site of the heat shield from NASA's Mars exploration rover Opportunity.

PHOTOGRAPH BY NASA, JPL, CORNELLSand dunes are among the most widespread aeolian, or wind-blown, features on Mars. These areas provide clues to the sedimentary history of the surrounding terrain.

PHOTOGRAPH BY NASA/JPL-CALTECH/UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONAGroups of dark brown streaks were photographed by the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter on melting pinkish sand dunes covered with light frost.

PHOTOGRAPH BY HIRISE, NASAThe panoramic camera on NASA's Mars exploration rover Opportunity captured this scene of the west rim of the Endeavour crater during the summer of 2014.

PHOTOGRAPH BY NASA, JPL, HIRISESand dunes litter the floor of Aram Chaos, an eroded impact crater east of Mars's Valles Marineris canyon range.

PHOTOGRAPH BY NASA JPL-CALTECH, UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONAMelas Chasma is the widest segment of Valles Marineris, the largest canyon in the solar system.

PHOTOGRAPH BY NASA, JPL, UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONAThe Opportunity rover spent four months perched on the northern slope of Greely Haven and snapped more than 800 images of its surroundings.

PHOTOGRAPH BY NASAThe Russell crater dunes are a favorite target for the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter's HiRISE camera, not only because of their incredible beauty, but for measuring the accumulation of frost each fall and its disappearance in the spring.

PHOTOGRAPH BY NASAThe holes visible in this image are not impact craters, but rather material that was ejected from a large crater called Hale that does not appear here. Explosions formed moats, which have been partially covered over time by sand dunes (top).

PHOTOGRAPH BY HIRISE, JPL, NASANASA's Curiosity rover snapped this 360-degree panorama as part of a long-term campaign to document the context and details of the geology and landforms along Curiosity's traverse since landing in 2012.

PHOTOGRAPH BY JPL, NASARecurring slope lineae (RSL) are seasonal flows on warm slopes and are especially common in central and eastern Valles Marineris.

PHOTOGRAPH BY JPL, NASAVictoria crater has a distinctive "scalloped" shape to its rim, caused by erosion and downhill movement of crater wall material.

PHOTOGRAPH BY HIRISE, NASADust accumulation on a rover's solar panels reduces its power supply, and the rover's mobility is limited until winter is over or wind cleans the panels.

PHOTOGRAPH BY NASAThe Curiosity rover captured the Bagnold Dunes inside Gale crater on September 25, 2015.

PHOTOGRAPH BY NASAPartially exposed bedrock is exposed within the Koval'sky impact basin.

PHOTOGRAPH BY HIRISE, JPL, NASAThis dramatic, fresh impact crater spans approximately 100 feet (30 meters) in diameter and is surrounded by a large, rayed blast zone.

PHOTOGRAPH BY NASAThe north polar layered deposits are layers of dusty ice up to three kilometers (two miles) thick and approximately 1,000 kilometers (620 miles) in diameter.

PHOTOGRAPH BY NASASand dunes are among the most widespread wind-formed features on Mars. Their distribution and shapes are affected by changes in wind direction and wind strength.

PHOTOGRAPH BY NASAThis selfie from NASA's Curiosity rover shows the vehice at the site where it reached down to drill into a rock target called "Buckskin" on lower Mount Sharp.

PHOTOGRAPH BY NASAResearchers used the Curiosity rover in March 2015 to examine the structure and composition of the crisscrossing veins at the "Garden City" site in the center of this scene.

PHOTOGRAPH BY NASAThis crater near Sirenum Fossae has steep inner slopes carved by gullies.

PHOTOGRAPH BY NASAThis image covers many shallow irregular pits with raised rims, but researchers aren't sure how these odd features formed.

PHOTOGRAPH BY NASAAt this site in the lower mounter in Gale crater, orbiting instruments have detected signatures of both clay minerals and sulfate salts. This change in mineralogy may reflect a change in the ancient environment in Gale crater.

PHOTOGRAPH BY NASAViscous, lobate flow features are commonly found at the bases of slopes in the mid-latitudes of Mars and are often associated with gullies.

PHOTOGRAPH BY NASAMany Martian landscapes contain features that are similar to ones we find on Earth, like river valleys, cliffs, glaciers, and volcanoes.

PHOTOGRAPH BY NASATwo of the raised treads, called grousers, on the left middle wheel of NASA's Curiosity rover broke during the first quarter of 2017, including the one seen partially detached at the top of the wheel in this image from the camera on the rover's arm.

PHOTOGRAPH BY NASAIn the scenic Murray Buttes area, individual buttes and mesas were assigned numbers. This one is referred to as "M9a."

PHOTOGRAPH BY NASAThis observation from NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter shows late summer in Mars's southern hemisphere. The sun is low in the sky, highlighting the subtle topography.

PHOTOGRAPH BY NASANASA's Curiosity rover team has assessed the small bright object just below the center of this image and believe it is debris from the spacecraft.

PHOTOGRAPH BY NASAThe High Dune, which is part of the Bagnold Dunes, was the first Martian sand dune ever studied up close. The dunes are active, migrating up to about one yard or meter per year.

PHOTOGRAPH BY NASAA towering dust devil casts a serpentine shadow over the Martian surface in this stunning late-springtime image of Amazonis Planitia.

PHOTOGRAPH BY NASALandforms called "gullies" found on many large Martian sand dunes consist of an alcove, channel, and apron.

PHOTOGRAPH BY NASANASA plans to launch another rover to Mars in 2020.

PHOTOGRAPH BY NASAIf there’s going to be a really inclusive effort to go beyond Earth, it has to start here on Earth. It can’t just be a tokenization of what the first crew might look like. It really has to be that people from a wider range of experiences and backgrounds—whether that means socioeconomic, racial, gender, whatever—are included in STEM in general. None of those narratives will become more inclusive until the people shaping them can become more inclusive. Otherwise, it’s just lip service.

There are much more direct examples, too. Most notably, Jeff Bezos saying that he has so much money now that he can’t think of anything to spend it on that isn’t space tourism. He lives in Seattle, a city where Amazon itself has changed people’s access to affordable housing. The city has been gentrified out of control, with large new developments that house lots of Amazon employees now sitting on community centers that I cooked food for the homeless in. Or, Elon Musk wearing an Occupy Mars shirt, which is totally and completely ridiculous when compared to what the Occupy movement is. There’s another thing you can’t take out of context.

How confident are you that people will buy into the idea that space is for everyone, and not just a playground for people who can afford it?

The governing document that sets forth all of space law, the Outer Space Treaty of 1967, literally says that space is for everyone. I mean, it’s 1967, so it says “for all mankind,” but if we edit that to be in the sense of the document, the outer space treaty says that space is for humankind, and that it is not to be owned by any individual or nation. It bars things like weapons of mass destruction, and it says outright that you cannot have a military installation on a celestial body.

When you look at the Outer Space Treaty, it’s this really aspirational document that contains a lot of really good things about the ways that we can and cannot explore space. However, if you read indigenous scholarship, or you listen to indigenous people, you’ll know that treaties get broken all the time. Literally every single treaty, over 500 of them that have been made with indigenous nations by the United States, have been broken.

I think that this is the moment, as it becomes more possible for a wider range of actors—whether they be nations or individual or otherwise—to go to space, when we have to decide whether those guiding principles are what we really want. This is the moment when we have to look at that treaty and decide who we want to be in the future.

Quelle: NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC