8.11.2018

Maunakea, Hawaii – Two galaxies, drawn together by the force of gravity, are merging into a tangled mass of dense gas and dust. Structure is giving way to chaos, but hiding behind this messy cloud of material are two supermassive black holes, nestled at the center of each of the galaxies, that are now excitingly close, giving astronomers the best view yet of the pair marching toward coalescence into one mega black hole.

“Seeing the pairs of merging galaxy nuclei associated with “huge” black holes so close together was pretty amazing,” said study leader, Michael Koss of Eureka Scientific Inc. in Kirkland, Washington. “The images are pretty powerful since they are ten times sharper than images from normal telescopes on the ground. It’s similar to going from legally blind (20/200 vision) to perfect 20/20 vision when you put on your eyeglasses. In our study, we see two galaxy nuclei right when the images were taken. You can’t argue with it; it’s a very clean result which doesn’t rely on interpretation.”

The team’s results appear online in the November 7, 2018 issue of the journal Nature.

Koss and his team of researchers made the discovery after completing the largest systematic survey of nearby galaxies using high-resolution images taken with W. M. Keck Observatory’s adaptive optics (AO) system and near-infrared camera (NIRC2), along with over 20 years of archival Hubble Space Telescope images. With this survey, astronomers can pinpoint the type of galaxy most likely to harbor close pairs of supermassive black holes.

“This is the first large systematic survey of 500 galaxies that really isolated these hidden late stage black hole mergers that are heavily obscured and highly luminous,” said Koss. “It’s the first time this population has really been discovered. We found a surprising number of supermassive black holes growing larger and faster in the final stages of galaxy mergers.”

Theory states that there is a supermassive black hole at the center of every large galaxy. When galaxies merge, so do their supermassive black holes. This process takes billions of years, but ends in a blink of an eye. A supermassive black hole merger has never been directly observed via electromagnetic radiation.

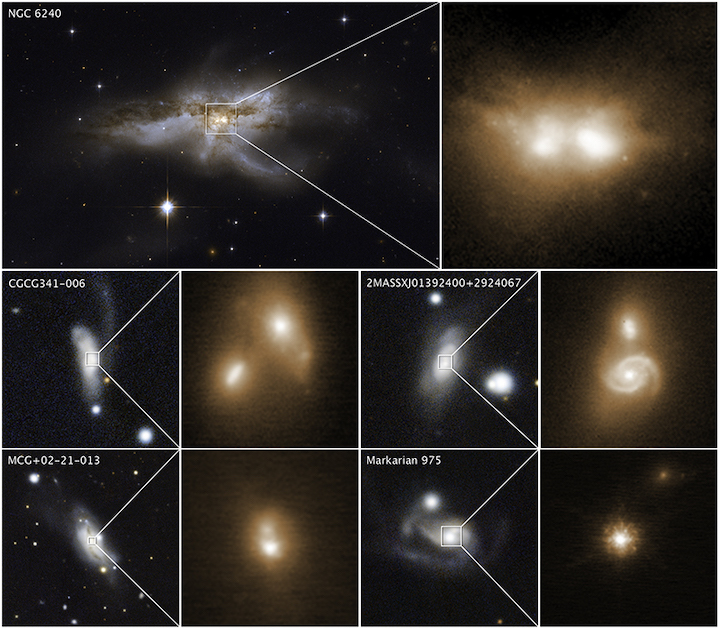

These images reveal the final stage of a union between pairs of galactic nuclei in the messy cores of colliding galaxies. The image at top left, taken by Hubble’s Wide Field Camera 3, shows the merging galaxy NGC 6240. A close-up of the two brilliant cores of this galactic union is shown at top right. This view, taken in infrared light, pierces the dense cloud of dust and gas encasing the two colliding galaxies and uncovers the active cores. The hefty black holes in these cores are growing quickly as they feast on gas kicked up by the galaxy merger. The black holes’ speedy growth occurs during the last 10 million to 20 million years of the merger. Images of four other colliding galaxies, along with close-up views of their coalescing nuclei in the bright cores, are shown beneath the snapshots of NGC 6240. The images of the bright cores were taken in near-infrared light by the W. M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii, using adaptive optics to sharpen the view. The reference images (left) of the merging galaxies were taken by the Panoramic Survey Telescope and Rapid Response System (Pan-STARRS). The two nuclei in the Hubble and Keck Observatory photos are only about 3,000 light-years apart — a near embrace in cosmic terms. If there are pairs of black holes, they will likely merge within the next 10 million years to form a more massive black hole. These observations are part of the largest-ever survey of the cores of nearby galaxies using high-resolution images in near-infrared light taken by the Hubble and Keck observatories. The survey galaxies’ average distance is 330 million light-years from Earth. CREDIT: NASA/ESA/M. KOSS (EUREKA SCIENTIFIC, INC.)/PAN-STARRS/W. M. KECK OBSERVATORY

-

It’s not easy finding galaxy nuclei so close together either. The late stage of the merger process is so elusive because the interacting galaxies kick up a lot of gas and dust, especially in the final, most violent stages of the merger. A thick curtain of material forms and shields the galaxy nuclei from view in visible light. Astronomers did not have the capability to observe this type of event until now.

“Heavily obscured galaxy nuclei don’t have a bright point source in the center like a lot of luminous unobscured supermassive black holes do,” said Koss. “But we were able to detect them thanks to X-ray data from the Burst Alert Telescope (BAT). We then used the superior laser capability of Keck Observatory’s AO system to perform high-resolution, near-infrared imaging to distinctly see a double nucleus through the gas and dust and uncover the hidden mergers.”

Koss and his team’s findings support the theory that galaxy mergers explain how some supermassive black holes become so monstrously large.

“There are competing ideas; one idea is that you have a bunch of gas in the galaxy that slowly feeds the supermassive black hole. The other is idea is that you need galaxy mergers to trigger large growth. Our data argues for the second case, that these galaxy mergers are really critical in fueling the growth of supermassive black holes,” said Koss.

This survey may also help astronomers observe a black hole merger. When supermassive black holes collide, not only do they create a mega black hole, they can also unleash powerful energy in the form of gravitational waves. These ripples in space-time, which were predicted by Einstein, were recently detected in 2016 by groundbreaking experiments.

Like a siren before a tsunami, gravitational waves reach Earth slightly earlier than light. In order to image such an event, astronomers need to know where to look and what object to look for. Gravitational wave detectors tell astronomers what area, and Koss’ research tells them whether that object is likely to host a supermassive black hole merger.

Koss and his team focused on galaxies with an average distance of 330 million light-years from Earth. Many of the galaxies are similar in size to the Milky Way. The images presage what will likely happen in our own cosmic backyard, in about a billion years, when our Milky Way merges with the neighboring Andromeda galaxy and their respective central black holes will smash together.

The next step for Koss and his team is to follow up on these hidden black hole mergers with Keck Observatory’s instrument, the OH-Suppressing Infra-Red Imaging Spectrograph (OSIRIS). OSIRIS will allow them to measure both the rotation rate and mass of the black holes, which would make it possible to estimate how long it will take before the supermassive black holes collide and how strong the gravitational wave signal might be. OSIRIS data will also look for signs to see if the two black holes are both growing simultaneously.

Adaptive optics is a technique used to correct for the blurring effect of the Earth’s atmosphere. W. M. Keck Observatory’s laser guide star adaptive optics (LGS AO) system uses a laser to create an artificial star to measure for atmospheric distortions. This results in sharp, high-resolution images that allow astronomers to see celestial objects, such as hidden galaxy mergers, in ultra-fine detail. CREDIT: BILLY DOANER

-

ABOUT ADAPTIVE OPTICS

W. M. Keck Observatory is a distinguished leader in the field of adaptive optics (AO), a breakthrough technology that removes the distortions caused by the turbulence in the Earth’s atmosphere. Keck Observatory pioneered the astronomical use of both natural guide star (NGS) and laser guide star adaptive optics (LGS AO) on large telescopes and current systems now deliver images three to four times sharper than the Hubble Space Telescope. Keck AO has imaged the four massive planets orbiting the star HR8799, measured the mass of the giant black hole at the center of our Milky Way Galaxy, discovered new supernovae in distant galaxies, and identified the specific stars that were their progenitors. Support for this technology was generously provided by the Bob and Renee Parsons Foundation, Change Happens Foundation, Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, Mt. Cuba Astronomical Foundation, NASA, NSF, and W. M. Keck Foundation.

ABOUT NIRC2

The Near-Infrared Camera, second generation (NIRC2) works in combination with the Keck II adaptive optics system to obtain very sharp images at near-infrared wavelengths, achieving spatial resolutions comparable to or better than those achieved by the Hubble Space Telescope at optical wavelengths. NIRC2 is probably best known for helping to provide definitive proof of a central massive black hole at the center of our galaxy. Astronomers also use NIRC2 to map surface features of solar system bodies, detect planets orbiting other stars, and study detailed morphology of distant galaxies.

ABOUT W. M. KECK OBSERVATORY

The W. M. Keck Observatory telescopes are among the most scientifically productive on Earth. The two, 10-meter optical/infrared telescopes atop Maunakea on the Island of Hawaii feature a suite of advanced instruments including imagers, multi-object spectrographs, high-resolution spectrographs, integral-field spectrometers, and world-leading laser guide star adaptive optics systems. The data presented herein were obtained at Keck Observatory, which is a private 501(c) 3 non-profit organization operated as a scientific partnership among the California Institute of Technology, the University of California, and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. The Observatory was made possible by the generous financial support of the W. M. Keck Foundation. The authors recognize and acknowledge the very significant cultural role and reverence that the summit of Maunakea has always had within the Native Hawaiian community. We are most fortunate to have the opportunity to conduct observations from this mountain.

Quelle: W. M. KECK OBSERVATORY

---

Update: 9.11.2018

.

Astronomers Find Pairs of Black Holes at the Centers of Merging Galaxies

Observations reveal early stages of black hole mergers during final stages of galaxy coalescence

For the first time, a team of astronomers has observed several pairs of galaxies in the final stages of merging together into single, larger galaxies. Peering through thick walls of gas and dust surrounding the merging galaxies’ messy cores, the research team captured pairs of supermassive black holes—each of which once occupied the center of one of the two original smaller galaxies—drawing closer together before they coalesce into one giant black hole.

Led by University of Maryland alumnus Michael Koss (M.S. ’07, Ph.D. ’11, astronomy), a research scientist at Eureka Scientific, Inc., with contributions from UMD astronomers, the team surveyed hundreds of nearby galaxies using imagery from the W.M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii and NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope. The Hubble observations represent more than 20 years’ worth of images from the telescope’s lengthy archive. The team described their findings in a research paper published on November 8, 2018, in the journal Nature.

“Seeing the pairs of merging galaxy nuclei associated with these huge black holes so close together was pretty amazing,” Koss said. “In our study, we see two galaxy nuclei right when the images were taken. You can’t argue with it; it’s a very ‘clean’ result, which doesn’t rely on interpretation.”

The high-resolution images also provide a close-up preview of a phenomenon that astronomers suspect was more common in the early universe, when galaxy mergers were more frequent. When the black holes finally do collide, they will unleash powerful energy in the form of gravitational waves—ripples in space-time recently detected for the first time by the twin Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (LIGO) detectors.

The images also presage what will likely happen in a few billion years, when our Milky Way galaxy merges with the neighboring Andromeda galaxy. Both galaxies host supermassive black holes at their center, which will eventually smash together and merge into one larger black hole.

The team was inspired by a Hubble image of two interacting galaxies collectively called NGC 6240, which later served as a prototype for the study. The team first searched for visually obscured, active black holes by sifting through 10 years’ worth of X-ray data from the Burst Alert Telescope (BAT) aboard NASA’s Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory.

“The advantage to using Swift’s BAT is that it observes high-energy, ‘hard’ X-rays,” said study co-author Richard Mushotzky, a professor of astronomy at UMD and a fellow of the Joint Space-Science Institute (JSI). “These X-rays penetrate through the thick clouds of dust and gas that surround active galaxies, allowing the BAT to see things that are literally invisible in other wavelengths.”

The researchers then combed through the Hubble archive, zeroing in on the merging galaxies they spotted in the X-ray data. They then used the Keck telescope’s super-sharp, near-infrared vision to observe a larger sample of the X-ray-producing black holes not found in the Hubble archive.

The team targeted galaxies located an average of 330 million light-years from Earth—relatively close by in cosmic terms. Many of the galaxies are similar in size to the Milky Way and Andromeda galaxies. In total, the team analyzed 96 galaxies observed with the Keck telescope and 385 galaxies from the Hubble archive.

Their results suggest that more than 17 percent of these galaxies host a pair of black holes at their center, which are locked in the late stages of spiraling ever closer together before merging into a single, ultra-massive black hole. The researchers were surprised to find such a high fraction of late-stage mergers, because most simulations suggest that black hole pairs spend very little time in this phase.

To check their results, the researchers compared the survey galaxies with a control group of 176 other galaxies from the Hubble archive that lack actively growing black holes. In this group, only about one percent of the surveyed galaxies were suspected to host pairs of black holes in the later stages of merging together.

This last step helped the researchers confirm that the luminous galactic cores found in their census of dusty interacting galaxies are indeed a signature of rapidly-growing black hole pairs headed for a collision. According to the researchers, this finding is consistent with theoretical predictions, but until now, had not been verified by direct observations.

“People had conducted studies to look for these close interacting black holes before, but what really enabled this particular study were the X-rays that can break through the cocoon of dust,” explained Koss. “We also looked a bit farther in the universe so that we could survey a larger volume of space, giving us a greater chance of finding more luminous, rapidly-growing black holes.”

It is not easy to find galactic nuclei so close together. Most prior observations of merging galaxies have caught the coalescing black holes at earlier stages, when they were about 10 times farther away. The late stage of the merger process is so elusive because the interacting galaxies are encased in dense dust and gas, requiring very high-resolution observations that can see through the clouds and pinpoint the two merging nuclei.

“Computer simulations of galaxy smashups show us that black holes grow fastest during the final stages of mergers, near the time when the black holes interact, and that’s what we have found in our survey,” said Laura Blecha, an assistant professor of physics at the University of Florida and a co-author of the study. Blecha was a JSI Prize Postdoctoral Fellow in the UMD Department of Astronomy prior to joining UF’s faculty in 2017. “The fact that black holes grow faster and faster as mergers progress tells us galaxy encounters are really important for our understanding of how these objects got to be so monstrously big.”

Future infrared telescopes such as NASA’s highly anticipated James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), slated for launch in 2021, will provide an even better view of mergers in dusty, heavily obscured galaxies. For nearby black hole pairs, JWST should also be capable of measuring the masses, growth rates and other physical parameters for each black hole.

“There might be other objects that we missed. Even with Hubble, many nearby galaxies at low redshift cannot be resolved—the two nuclei just merge into one,” said study co-author Sylvain Veilleux, a professor of astronomy at UMD and a JSI Fellow. “With JWST’s higher angular resolution and sensitivity to the infrared, which can pass through the dusty cores of these galaxies, searches for these nearby objects should be easy to do. Also with JWST, we will be able to push toward larger distances, to see objects at higher redshift. With these observations, we can begin to explore the fraction of objects that are merging in the youngest, most distant regions of the universe—which should be fairly frequent.”

VIDEO: Galaxy Merger Simulation + Keck Observations

###

This press release was adapted from text provided by NASA.

The research paper, “A Population of Luminous Accreting Black Holes with Hidden Mergers,” Michael Koss, Laura Blecha, Phillip Bernhard, Chao-Ling Hung, Jessica Lu, Benny Trakthenbrot, Ezequiel Treister, Anna Weigel, Lia Sartori, Richard Mushotzky, Kevin Schawinski, Claudio Ricci, Sylvain Veilleux and David Sanders, was published in the journal Nature on November 8, 2018.

This work was supported by NASA (Award No. NNH16CT03C) and the Swiss National Science Foundation (Award Nos. PZ00P2 154799/1, PP00P2 138979, and PP00P2 166159). The content of this article does not necessarily reflect the views of these organizations.

Media Relations Contact: Matthew Wright, 301-405-9267, mewright@umd.edu

Quelle: University of Maryland