The Chang'e-4 lander, with the rover on top, undergoing tests.

19.10.2018

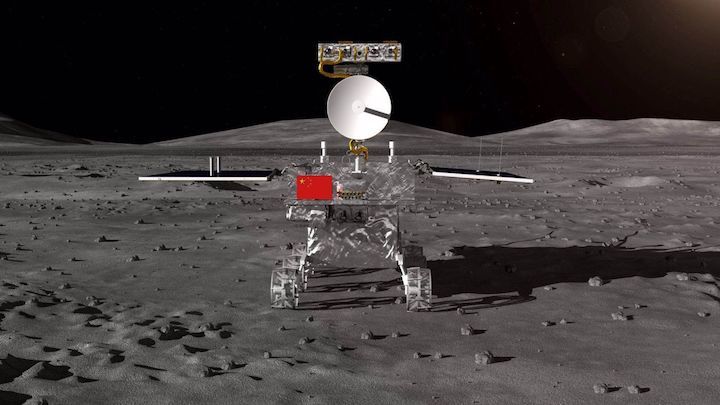

A render of China's Chang’e-4 moon rover that is expected to land on the far side of the Moon around December 2018. CNSA

A popular vote has decided the top three names from a shortlist of ten as part of a contest to the name the rover belonging to China's ambitious Chang'e-4 lunar far side landing mission, which is set to launch in December.

The shortlist was created following a public call in August for submissions to solicit names for the pioneering Moon mission.

After voting closed on October 10, it appears the clear favourite was 'Brightness' (光明, guangming) with 124,108 votes (Chinese) and 39 percent of the vote.

Second was 'Wang Shu' (望舒, a lunar-related deity from folklore) with 78,156 votes and 25 percent, with 'Stroller' or 'Hiker' (行者, xingzhe, a name linked to Journey to the West) in third place with 48,863 and 16 percent of the votes.

The final choice will be decided by a committee in late October, according to earlier reports. A science seminar to be held in Beijing on October 24 and 25 could see the name ratified.

The contest was initiated to popularise the mission and China's space achievements. A similar competition was held in 2013 and gave the name Yutu (Jade Rabbit) to the Chang'e-3 rover.

Chang'e-4 is a repurposed backup to the Chang'e-3 mission and will, after launch in December, attempt the first ever landing on the far side of the Moon, which never faces the Earth.

The mission is made possible by a relay satellite, named Queqiao, which is in a halo orbit at a Lagrange point beyond the Moon to facilitate communications between ground stations and spacecraft on the far side of the Moon.

The Chang'e-4 lander, with the rover on top, undergoing tests.

The reliability of the new rover has been improved based on lessons from Chang'e-3, which saw Yutu come to a permanent halt after 114 metres. Nevertheless, it continued to carry out its scientific tasks.

A demonstration of the lissajous/halo orbit orbit to be used by the Queqiao Chang'e-4 relay satellite mission.

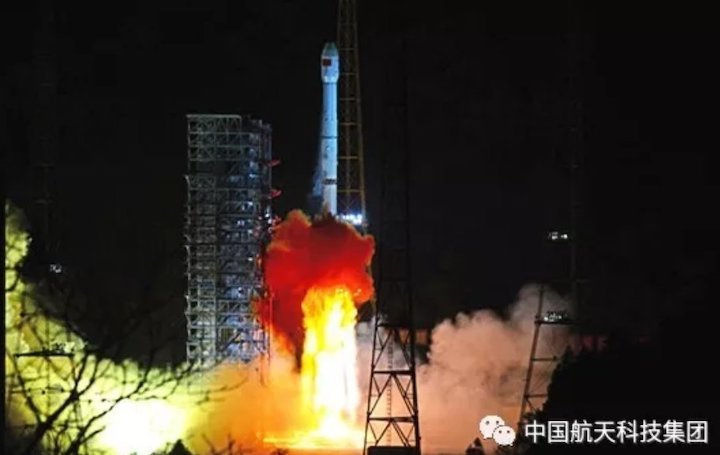

A Long March 3B rocket will launch the Chang'e-4 spacecraft from the Xichang Satellite Launch Centre, which has hosted all five of China's lunar mission launches so far. Launch is rumoured to be set for December 8, with a landing around December 30 or 31.

The lander and rover will target a landing within the South Pole-Aitken Basin, a huge and scientifically significant impact crater on the far side of the Moon.

The Von Kármán crater is understood to contain the selected landing site, according to a paper published by Huang Jun et al in the American Geophysical Union’s Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets.

See our Chang'e-4 feature for the latest news and background on the lunar far side mission.

The white box indicates the Chang'e-4 landing area within the Von Kármán crater, according to a paper from Huang Jun et al, 2018.

A 1:1 model of the Tianhe core module of the Chinese Space Station on display at the 2018 Zhuhai Airshow. CNS

Chinese space technology, including a full size model space station module, the Chang'e-4 lunar far side spacecraft and new launch vehicles, have been unveiled at the Zhuhai Airshow in southern China.

The full size model represents the first time the 'Tianhe' core module for the future Chinese Space Station has been on display to the public.

The 16.6m-long module consists of a 4.2m-diameter resources compartment, a 2.8m-diameter life support and control section, and the docking hub, which will facilitate connection with further modules and visiting Shenzhou-crewed spacecraft and Tianzhou cargo vessels.

Wang Xin, deputy director general of the Space Station System project, under the China Academy of Space Technology (CAST), told CCTV that the rear docking hatch would be used to dock with Tianzhou freight spacecraft, while the robotic arms on display are to be used for on-orbit assembly and other operations.

The Chinese Space Station core module Tianhe on display at the 2018 Zhuhai Airshow (Chinese language).

The Tianhe module will be the first of three 20-metric-tonne modules that will make up the Chinese Space Station (CSS), along with two experiment modules to be used for a range of science objectives.

Launch is scheduled for 2020, after a necessary successful test flight of the Long March 5B rocket being developed to launch the modules. This was delayed by the failure of the Long March 5 in July 2017, and a return-to-flight will be attempted in early 2019.

A view of the Tianhe living compartment, with five Control Moment Gyroscopes (CMGs) visible.

The Zhuhai Airshow, which runs from November 6-11, also features exhibits containing model Long March launch vehicles and the spacecraft for the Chang'e-4 lunar mission, which in December will attempt the first ever landing on the far side of the Moon.

Models of the Chang'e-4 lander and rover, as well as the Queqiao relay satellite, were out on view.

A model of the Chang'e-4 lander at the 2018 Zhuhai Airshow.

The mission will be made possible by a relay satellite named Queqiao, which is in a halo orbit at a Lagrange point beyond the Moon to facilitate communications between ground stations and spacecraft on the far side of the Moon.

A Long March 3B rocket will launch the Chang'e-4 spacecraft from the Xichang Satellite Launch Centre, which has hosted all five of China's lunar mission launches so far. Launch is rumoured to be set for December 8, with a landing around December 30 or 31.

See our Chang'e-4 feature for the latest news and background on the lunar far side mission.

A model of the Chang'e-4 rover at the 2018 Zhuhai Airshow.

On the sidelines of the Zhuhai Airshow, Zhao Jian, deputy director of the Department of Systemic Engineering under the China National Space Administration (CNSA), reiterated China's plans to launch four deep space missions before 2030.

The 2020 orbiter and rover mission to Mars—China's first independent interplanetary mission— will be followed by a mission to explore asteroids and smaller bodies around 2022.

A second Mars visit is targeted for 2028, which will be an as yet unprecedented sample return mission from the Red Planet. A Jupiter orbiter mission, launching around 2030, was the final mission noted.

The video below first demonstrates the Chang'e-5 lunar sample return mission, which could launch in late 2019.

China to conduct four Deep Space Exploration Missions on Mars, Asteroids, Jupiter.

Zhuhai also offered the first look at China's heavy-lift carrier rocket Long March 9, which is still under development, with China aiming for a first flight in 2028.

"The Long March 9 rocket would have a core stage with a diameter of 10 metres, which would double the five-metre core stage of the Long March 5. Length of the Long March 9 has exceeded 100 metres, so it would be the largest carrier rocket of China, and possibly of the world, according to currently known planning," said Zhang Zhi, chief designer of the Long March 9 rocket with the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC).

China is also developing a medium-lift rocket, the Long March 8, to carry payloads of up to 4.5 tonnes into Sun-synchronous orbit (SSO) at an altitude of 517 km. It is expected to make its debut flight in 2020, featuring a new modular design and reusable technology.

Also on display is the microsatellite rocket Smart Dragon 1, also known as Lightning Dragon 1, which was developed by the commercial entity Chinarocket under CASC. it is expected to have a carrying capacity of 150 kilogrammes to SSO.

China’s new rockets: Long March-9, Long March-8 and Smart Dragon-1.

Quelle: gbtimes

----

Update: 28.11.2018

.

China's Yuanwang 7 space tracking ship sets sail for Pacific waters on the morning of November 26, 2018. CNS

China's Yuanwang 7 space tracking vessel is heading for waters in the Pacific Ocean in preparation to support the Chang'e-4 lunar far side lander and rover mission, expected to launch in early December.

Yuanwang 7 departed port in Jiangyin in Jiangsu Province on the Yangtze River early on Monday morning.

Announcements (Chinese) of the departure did not specifically mention the Chang'e-4 mission, but the activity fits with the understood launch date of early December 8 Beijing time (late December 7 universal time).

Chang'e-4 is due to make the first-ever attempt at a soft-landing on the far side of the Moon, which never faces the Earth, with a lander and rover carrying an array of science payloads and experiments.

The mission will target the South Pole-Aitken Basin, a huge impact crater on the southern hemisphere of the far side of the Moon, with the landing likely to take place around the New Year.

The 220-metre-long, 40-m-high Yuanwang 7 and another ship from the fleet are expected to be deployed to provide communication with and control over the rocket and spacecraft downrange following launch from the Xichang Satellite Launch Centre.

China's Yuanwang 7 space tracking ship sets sail for Pacific waters on the morning of November 26, 2018.

Yuanwang 7 is China's newest space tracking ship, having been launched in July 2016, and was involved in the Shenzhou-11 human spaceflight mission, the debut flight of the heavy-lift Long March 5, the Tianzhou-1 cargo spacecraft launch and that of Queqiao, the relay satellite that will facilitate communications for the Chang'e-4 mission, in May, together with Yuanwang 6.

The relay satellite is required to be in place to facilitate communications between terrestrial ground stations and the Chang'e-4 lander and rover. Its intended halo orbit around the second Earth-Moon Lagrange point more than 60,000 kilometres beyond the Moon will make it accessible to both ground stations on Earth and the lander on the lunar far side at all times.

A rendering of the Queqiao Chang'e-4 lunar relay satellite.

The Yuanwang ships, whose name means 'long view', are equipped with an array of dishes and electronics to support the launching and tracking of space launch vehicles. They observe trajectories and provide survey and control capabilities as rockets fly downrange.

Shortly after launch of the crewed Shenzhou-11 mission, Yuanwang 7 tracked the spacecraft for nearly 400 seconds and issued orders for the unfolding of solar panels and antenna, and perform other movements after entering orbit.

Yuanwang 7 Maritime Tracking of Shenzhou-11 Completed

China has four Yuanwang tracking ships in active service: Yuanwang 3, 5, 6 and 7. Two further ships, Yuanwang-21 and -22, were specially designed for transporting the components of the Long March 5 heavy-lift rocket from the city of manufacture, Tianjin in the north, to Hainan island in the south, which hosts the new Wenchang Satellite Launch Centre, as the 5-m-diameter Long March 5 is too large to be transported via the country's rail system.

The Yuanwang ships are under the control of the China Satellite Launch and Tracking Control General (CLTC), subordinate to the People's Liberation Army General Arms department.

Quelle: gbtimes

----

Update: 5.12.2018

.

The far side of the Moon and the distant Earth, imaged by the Chang'e-5T1 mission in 2014. Chinese Academy of Sciences

China will launch its Chang'e-4 lunar mission on December 7 universal time which will see a lander and rover spacecraft make the first ever attempt to land on the far side of the Moon.

According to airspace closure notices issued on Wednesday, the launch will take place between 18:15-18:34 universal time (13:15-13:34 Eastern) on Friday (02:15-02:34 Beijing time Saturday).

The Chang'e-4 lander and rover will launch atop an enhanced Long March 3B carrier rocket from the Xichang Satellite Launch Centre in southwest China.

There is currently no indication that the launch will be broadcast live, in which case the first official news after liftoff may only be provided once the spacecraft have successfully entered lunar transfer orbit.

The Chang'e-4 lander and rover spacecraft will together carry eight instruments, cameras and payloads for a range of scientific objectives, including low-frequency radio observations, solar wind activity and interaction with the lunar surface, and surface geology and subsurface investigation.

A lunar far side landing is unprecedented because that hemisphere cannot be viewed directly from the Earth, posing communications challenges which require innovative solutions.

The mission is ready to proceed following the May launch of the Queqiaorelay satellite, which in June established its intended halo orbit from which it will be able to simultaneously contact tracking stations on Earth and the spacecraft on the far side of the Moon.

A rendering of the Queqiao Chang'e-4 lunar satellite performing its communications relay functions beyond the Moon.

The mission will target an area within the South Pole-Aitken Basin, a huge, ancient and scientifically significant impact crater on the far side of the Moon, with a diameter of around 2,500 kilometres.

The Von Kármán crater is understood to contain the selected landing site, according to a papers published by Huang Jun et al in the American Geophysical Union’s Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, with other publications also analysing this crater.

Long Xiao, a Chinese planetary geologist, stated in the Planetary Society's Planetary Report magazine the landing coordinates to be 45°S – 46°S, 176.4°E – 178.8°E in the southern section of Von Kármán crater.

The white box indicates the Chang'e-4 landing area with the Von Kármán crater, according to a paper from Huang Jun et al, 2018.

No official date has been given for the landing, though indications are that it could take place on or around January 3, 2019.

China completed its first landing on the Moon in December 2013 with the Chang'e-3 mission. Chang'e-4 was originally the backup spacecraft and mission for Chang'e-3 and has now been repurposed for this more ambitious endeavour.

Chang'e-3 was the first soft-landing on the Moon since the mid-1970s, with a lander and the Yutu (Jade Rabbit) rover setting down on Mare Imbrium.

Yutu was designed to explore an area close to the landing site during its three-month design life, but travelled only around 110 metres before losing the capability to rove.

Li Ming, vice president of the China Academy of Space Technology (CAST) which designed and manufactured the spacecraft, said in October that there have been some improvements to the reliability of the new rover.

See our Chang'e-4 feature for the latest news and background on the lunar far side mission.

A render of China's Chang’e-4 moon rover that is expected to land on the far side of the Moon around December 2018.

Early Saturday morning in China, a rocket will launch, carrying a lander and a rover bound for the Moon. It will mark the beginning of China’s ambitious lunar mission known as Chang’e-4, which will attempt to land spacecraft on the Moon’s far side — the region that always faces away from Earth. No other nation has ever attempted such a feat — which means the mission could catapult China into spaceflight history.

So far, China is among an elite group of three countries that have landed a spacecraft softly on the surface of the Moon. Apart from America’s notable Apollo missions, the former Soviet Union also landed robotic spacecraft on the lunar surface, with the last mission occurring in 1976. In 2013, China entered the fray, putting a lander and a rover on the Moon. That mission, known as Chang’e-3, was part of a decades-long campaign that China devised to study the Moon with robotic spacecraft. Prior to Chang’e-3, the country had put a spacecraft in lunar orbit and had also crashed a vehicle into the lunar dirt. Now, the next step is to visit a part of the Moon that’s never been fully explored.

It’s a significant step because landing on the far side of the Moon is an incredibly challenging task. The Moon is tidally locked with Earth, meaning it rotates around its axis at about the same time it takes to complete one full orbit around our planet. The result: we only see one half of the Moon at all times. This near side of the Moon is the only region that we’ve landed on gently, because there’s a direct line of sight with Earth, enabling easier communication with ground control. To land on the far side of the Moon, you must have multiple spacecraft working in tandem. In addition to the lander itself, you need some kind of probe near the Moon that can relay communications from your lander to Earth.

And that’s exactly what China has. In May, the China National Space Administration launched a satellite called Queqiao, specifically for the purpose of aiding with communications for the upcoming Chang’e-4 mission. After about a month in space, Queqiao settled into a spot facing the far side of the Moon, more than 37,000 miles away from the lunar surface. The satellite is doing circles around a point in space known as the second Earth-Moon Lagrange point. It’s a place akin to a parking spot for spacecraft. At a Lagrange point, the gravitational forces of two bodies (stars, planets, etc) equal out in such a way that a spacecraft stays put in relation to the two entities. At this particular Lagrange point, Queqiao will stay facing the far side of the Moon, allowing communication between the spacecraft and Earth using a large curved antenna.

“Demonstrating that you can communicate and perform roving on the lunar far side using a relay satellite is going to be quite a technological feat, and it’s going to bring a lot of prestige,” Andrew Jones, a freelance journalist covering China’s spaceflight program, tells The Verge.

If it all works, China will be getting an up-close view of one of the most tantalizing areas of the lunar surface: the South Pole-Aitken basin. It’s believed that the Chang’e-4 lander and rover will touch down in the Von Kármán crater inside this region, according to Jones, though the exact landing site hasn’t been confirmed. The South Pole-Aitken basin is a large impact crater on the far side of the Moon that’s roughly 1,550 miles in diameter and 7.5 miles deep. It’s thought to be one of the oldest impact sites on the lunar surface, but we don’t know exactly how old it is — and its true age could tell scientists a lot about the early Solar System.

Most of the craters on the Moon are thought to have formed around 3.9 billion years ago, based on analysis of the lunar rocks collected during NASA’s Apollo missions. Many scientists think these holes occurred during a period of the Solar System known as the Late Heavy Bombardment — a period when a huge number of asteroids smacked into the inner planets. It’s thought this time occurred after most of the planets in our cosmic neighborhood had formed, which is why it’s considered “late” in our Solar System’s development. If the South Pole-Aitken basin is also 3.9 billion years old, it supports the idea that this bombardment happened. If it’s much older than that, it puts a dent in that theory. “This actually helps us understand not just about the Moon, but the whole Solar System,” Clive Neal, an engineering professor at the University of Notre Dame and emeritus chair of the Lunar Exploration Analysis Group, or LEAG, tells The Verge. “That’s why it’s important; it’s bigger than the Moon.”

Because of its potential to tell us about our history, the South Pole-Aitken basin has long been a priority target of study. Scientists have proposed sending spacecraft to this region in order to collect samples and return them to Earth for in-depth analysis. “The South Pole-Aitken basin is exceedingly important, and we still haven’t done it because it’s too difficult,” says Neal.

Unfortunately, Chang’e-4 won’t be returning anything to Earth, so it probably won’t be able to tell us the exact age of the basin. But it should learn a few interesting tidbits. The Chang’e-4 rover will be carrying ground-penetrating radar to figure out what the structure of the Moon is like underneath the surface of the basin, which could tell us more about how this area formed. It will also have an instrument designed to figure out what the surface is made of in this region. And it’s carrying a Swedish instrument designed to figure out how particles streaming from the Sun interact with the lunar rocks.

Meanwhile, the lander, which is tasked with carrying the rover to the Moon’s surface, will also be doing science from its landing spot, taking advantage of its location on the Moon. Since these vehicles will be on the Moon’s far side, they’ll be shielded from much of the electromagnetic interference from Earth and don’t have to deal with our planet’s atmosphere. The lander will be studying the space environment and the Universe in low frequencies — something we can’t do from our planet.

And of course, both the lander and the rover will carry cameras to take detailed images of the lunar surface, just as Chang’e-4’s predecessor, Chang’e-3, did. Much of the Chang’e-4 design is modeled after Chang’e-3, which landed on the nearside of the Moon and told scientists a great deal about an area known as the Imbrium basin. Hopefully, Chang’e-4’s rover will move farther than the rover on Chang’e-3, called Yutu, which stopped being able to travel after about a month.

While it’s definitely unique, Chang’e-4 is just one step in the ladder of China’s decade-long Chang’e mission plan (Chang’e is a goddess of the Moon in Chinese mythology). Following this mission, China plans to launch another robotic mission to the Moon next year called Chang’e-5, which is designed to return samples from the nearside of the Moon. If successful, it’ll be the first time lunar material has been brought back to Earth since 1976. Beyond that, Neal thinks that a sample return from the far side of the Moon is on the horizon. “Chang’e-4 is a first step, and I’m sure it will raise more questions than it answers,” says Neal. “But showing the capability is there to land on the far side and rove, that tells us what’s the next step, and, as I say, robotic sample return would be the logical next step.”

In the more distant future, it’s possible that China hopes to put people on the Moon, though it hasn’t been open about those plans. Jones says that it looks like China is working toward crewed flight, by developing a new huge launch vehicle and concepts for a rocket that can carry people. “There’s no officially government-approved plan to put Chinese astronauts on the moon, however you can see that they are working on the various components that you need,” he says.

Any human missions are still years away, and for now China is focused on Chang’e-4. But as is the case with many of China’s missions, the details surrounding this flight have been hard to come by. We know that the mission is set to launch on top of one of China’s Long March 3B rockets from the country’s Xichang Satellite Launch Center. And thanks to air closure notices, takeoff time is estimated to occur around 1:30PM ET on Friday, December 7th. China may only announce that the mission was a success after the spacecraft is on its way to the Moon, though Jones says we might hear earlier than that from other sources.

“It might be that the first indication we have of launch is that some poor soul near Xichang launch center is woken up thinking there’s an earthquake and complaining about it on social media.” Jones says.

If Chang’e-4 does make it to space, it will spend less than a month traveling to the Moon, likely touching down sometime in the first week of January. If that happens, China will have officially moved into its own elite group, as the only country to visit the side of the Moon we cannot see from Earth.

Quelle: The Verge

+++

Update: 20.15 MEZ

Quelle: China Daily