On its last orbits in 2017, the long-running Cassini spacecraft dove between Saturn’s rings and its upper atmosphere and bathed in a downpour of dust that astronomers call “ring rain.”

In research published today in Science, CU Boulder’s Hsiang-Wen (Sean) Hsu and his colleagues report that they successfully collected microscopic material streaming from the planet’s rings.

“Our measurements show what exactly these materials are, how they are distributed and how much dust is coming into Saturn,” said Hsu, lead author of the paper and a research associate at the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP).

The findings, which were made with Cassini’s Cosmic Dust Analyzer and Radio and Plasma Wave Science instruments, come a little more than a year after the spacecraft burned up in Saturn’s atmosphere. They stem from the mission’s “grand finale,” in which Cassini completed a series of risky maneuvers to zip under the planet’s rings at speeds of 75,000 miles per hour.

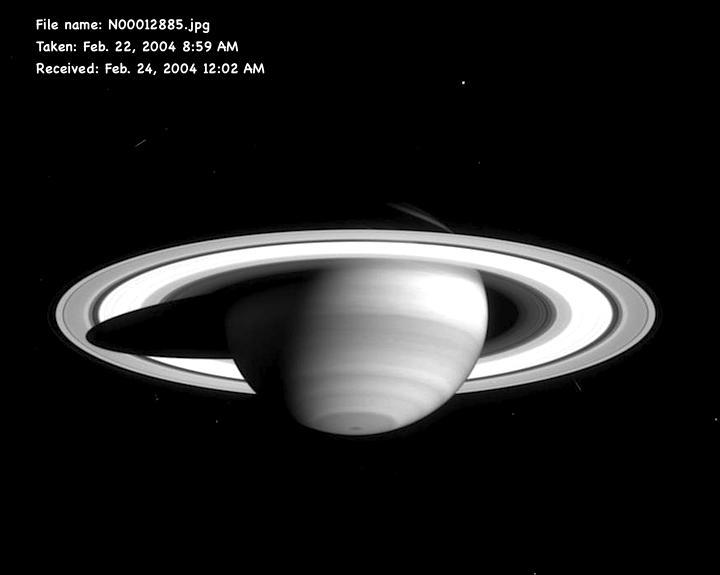

In its 22 "grand finale" orbits (blue), Cassini zipped through the 1,200 mile-wide space between the Saturn's rings and its atmosphere. The spacecraft's penultimate series of orbits (yellow) grazed the planet's outermost rings. (Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech)

Capturing dust under those conditions was an engineering and navigational coup, the researchers said—a snatch-and-run that the mission team had been planning since 2010.

“This is the first time that pieces from Saturn’s rings have been analyzed with a human-made instrument,” said Sascha Kempf, a co-author of the new study and a research associate at LASP and associate professor in the Department of Physics. “If you had asked us years ago if this was even possible, we would have told you ‘no way.’”

The research is one of a series of studies from Cassini’s last orbitsappearing today in Science. NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) managed the mission, which was a cooperative effort of NASA, the European Space Agency (ESA) and Italian Space Agency. Ralf Srama of the University of Stuttgart leads research using the spacecraft’s Cosmic Dust Analyzer, and William Kurth of the University of Iowa leads Radio and Plasma Wave Science.

Beautiful physics

Catching that ring rain—which astrophysicists had predicted based on studies of Saturn’s upper atmosphere—in action wasn’t easy: Getting too close to a planet’s rings risks shredding the spacecraft.

With Cassini running low on fuel in 2017, however, mission scientists decided to take the chance. Cassini made 22 passes around Saturn, threading between the planet’s closest ring and its upper atmosphere, a space less than 1,200 miles wide.

During eight of those final orbits, the Cosmic Dust Analyzer trapped more than 2,700 charged bits of dust. Based on the group’s calculations, that’s enough ring rain to send about one metric ton of material into Saturn’s atmosphere every second.

But those particles didn’t fall directly into the planet by gravity alone. Instead, the team suspects that they gyrate along Saturn’s magnetic field lines like a yo-yo before crashing into the atmosphere.

“It’s a beautiful display of physics at work,” said study co-author Mihály Horányi, a professor in physics at CU Boulder.

Dirty snowballs

The researchers were also able to study what that planetary dust was made of. Most of the particles were bits of water ice—the main component of Saturn’s rings. But the spacecraft also picked up a lot of tiny silicates, a class of molecules that make up many space rocks.

That finding is important, Hsu said, because it could help answer a nagging question about Saturn: how old are its rings? He explained that icy objects in space are a bit like bookshelves in your house.

“It is really difficult to maintain a pure ice surface in the solar system because you always have dirty material coming at you,” Hsu said. “One of the things we want to understand is how clean or dirty the rings are.”

If scientists can identify the exact types of silicates that coat Saturn’s rings, they may be able to tell whether those features are billions of years old or much younger. Hsu’s colleagues are currently working to make those identifications. Researchers at LASP are also building on what they learned from Cassini’s Cosmic Dust Analyzer to design similar dust-catching instruments for NASA’s Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe(IMAP) and Europa Clipper missions.

As for Cassini, “I am sure there will be surprises yet to come,” said Horányi, who is also a co-investigator on the Cosmic Dust Analyzer. “We still have enormous amounts of data that we have to sort out and analyze.”

Other co-authors on the study include researchers at the University of Oulu; Heidelberg University; Free University of Berlin; University of Stuttgart; Potsdam University; JPL; University of Iowa; NASA Goddard Space Flight Center; Boston University; NASA Ames Research Center; University College London; University of London; and Baylor University.

Quelle: University of Colorado Boulder