8.07.2018

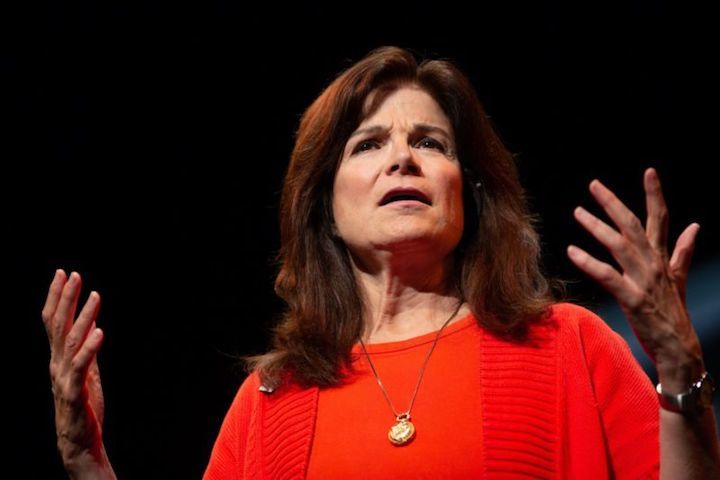

Planetary scientist Carolyn Porco speaks on stage at the National Geographic Awards on Thursday, June 14, 2018, at Lisner Auditorium in Washington, D.C.

In its quest to find extant life in the Solar System, NASA has focused its gaze on the Jovian moon Europa, home to what is likely the largest ocean known to humans. Over the next decade, the space agency is slated to launch not one, but two multi-billion dollar missions to the ice-encrusted world in hopes of finding signs of life.

Europa certainly has its champions in the scientific community, which conducts surveys every decade to establish top priorities. The exploration of this moon ranks atop the list of most desirable missions alongside returning some rocky material from Mars for study on Earth. But there is another world even deeper out in the Solar System that some scientists think may provide an even juicer target, Saturn’s moon Enceladus. This is a tiny world, measuring barely 500km across, with a surface gravity just one percent of that on Earth. But Enceladus also has a subsurface ocean.

“I have a bias, and I don’t deny that,” says Carolyn Porco, one of the foremost explorers of the Solar System and someone who played a key imaging role on the Voyagers, Cassini, and other iconic NASA spacecraft. “But it’s not so much an emotional attachment with objects that we study, it’s a point of view based on the evidence. We simply know more about Enceladus.”

Tiny moon

This is true. Whereas NASA’s Galileo probe explored the Jupiter system during the 1990s, the space agency sent a more capable probe to Saturn in the 2000s. That spacecraft spent 13 years in orbit around Saturn, and it found conclusive evidence of not only an ocean on Enceladus, but one that is accessible through its large geysers. These jets of icy particles soar as much as 500km above the surface because there is so little surface gravity to restrain them.

Moreover, Cassini was able to fly through these sprays on several occasions. Scientists studying data collected during multiple passes have confirmed that the ocean below is akin to deep oceans on Earth, and they have found the presence of large and complex organic molecules. All of this points to the possibility of life.

Scientists know less about Europa, said Porco, who recently spoke with Ars when she accepted the Eliza Scidmore Award at the 2018 National Geographic Explorers Festival. In contrast to Enceladus, for the plumes on Europa, scientists aren't sure whether these plumes originate from the ocean below Europa’s ice, or whether they contain any organic material at all.