ESA astronaut Samantha Cristoforetti in a Chinese pressure suit during training with Chinese colleagues to practise sea survival off China’s coastal city of Yantai, on 14 August 2017.

2.06.2018

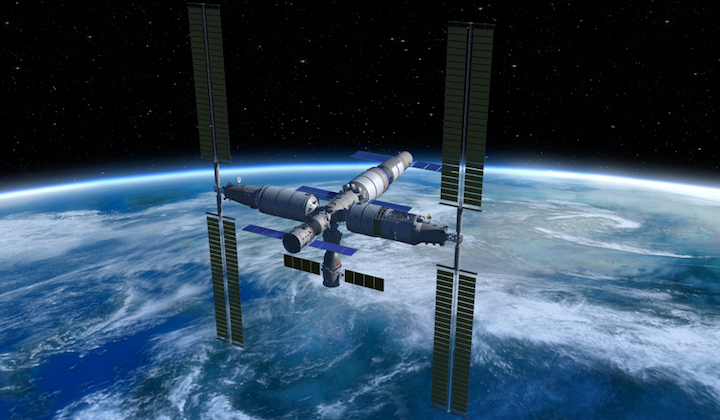

China this week opened its planned space station to international participation, in cooperation with the United Nations. The call for proposals for research to be carried out aboard the orbital facility has generally been welcomed, but what are China's motives for sharing its space station?

In general terms, sending humans to space is incredibly challenging and risky, and therefore expensive. China, like other nations, will look to reap all the dividends possible for its investment in the Chinese Space Station (CSS), a project started in 1992 that first sought to develop the capability to put astronauts in orbit.

While a project like the CSS builds capacity and high-technology capabilities, spurs innovation, brings scientific gains, inspires new generations and demonstrates to the domestic and international audiences what China, under Communist Party leadership is capable of, international cooperation brings further benefits, including leverage in diplomacy, but also gains in technology and experience from the outside and, potentially, sharing costs.

Prestige and soft power will be clear pay offs China will be looking for, says Dr Bleddyn Bowen, a lecturer in International Relations at the University of Leicester in the UK.

"Being international in space and encouraging international space science no doubt is a good thing for projecting China’s image as a peaceful rising power," Bowen says, adding that China may be taking cues from US, European and Russia experience with the International Space Station (ISS).

Bowen says that the CSS is a, "good investment in Chinese space science and engineering, especially for further space exploration missions to the Moon and beyond," but there is also a symbolism.

"What this means is that high-end international space science and human spaceflight operations, for the first time since the end of the Cold War, will be as much led by China as the USA – if the CSS attracts partners and successfully conducts the lofty goals assigned to it."

This initial invitation from the United Nations, through the Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA), and the China Manned Space Agency (CMSA), is limited to science research and payloads - like the UN and Japan's KiboCube initiative - Bowen notes that a very interesting question in terms of prestige and legitimacy seeking through space is who will be the first country to have a guest astronaut on a Chinese rocket.

The European Space Agency (ESA) has agreed among its members to pursue a long-term goal of sending one of its astronauts to the CSS, perhaps around a decade from now. Three ESA astronauts are currently learning Chinese as part of these efforts, and last year Samantha Cristoforetti and Matthias Maurer joined Chinese counterparts for joint sea survival training off the coast of Shandong Province, illustrating the steps taken on both sides towards a joint Chinese-European human spaceflight mission.

ESA astronaut Samantha Cristoforetti in a Chinese pressure suit during training with Chinese colleagues to practise sea survival off China’s coastal city of Yantai, on 14 August 2017.

However, agreements with other nations with no previous access to space could also materialise and be fast-tracked.

Overall, the type of partner that China attracts and chooses for CSS cooperation will impact how the project is run.

"The political and institutional basis of cooperation in CSS will naturally follow the spacepower of the primary partners or contributors of the CSS," Bowen explains. "For example, European or Russia participation will challenge Chinese unilateralism over the station. But a collection of developing states or weaker/smaller space powers like Nigeria, Angola, Cuba, Iran, or Peru will just be ‘along for the ride’ and will not be challenging grand Chinese designs of the station’s future and primary allocation of resources on it."

The devil will be in the detail, and naturally there will be concerns about intellectual property rights, industrial returns and financial contributions, Bowen elaborates.

Bowen states that the ISS was never a partnership of equals - being driven largely by the United States - but its treaty mechanism helped address those issues somewhat. When getting involved in the CSS, "any partner of China will likewise need to be shrewd in thinking how this can benefit them, without just giving China some political legitimacy with no serious returns for their own space sector and scientific and technological development," Bowen underlines.

Xinhua, China's state news agency, has been deploying a narrative of the CSS making space 'safer' in the wake of the announcement, asserting that the move, "further demonstrates China's unwavering belief that outer space is a common home for all humanity rather than a new battlefield."

Dr Bowen counters that this language should not disguise the fact that the CSS is part of a major Chinese space effort that is "modernising and enhancing Chinese power across all sectors, including military capabilities and its anti-satellite weapons capabilities."

"Be under no illusion: China, Russia and the United States are all preparing for the possibility of space warfare with the development of anti-satellite weapons," Bowen says.

The Chinese Space Station may open a new chapter of cooperation in low Earth orbit, but terrestrial politics and dynamics will remain in play.

The United States is meanwhile considering its next moves in human spaceflight. Though recently retired, Representative Frank Wolf has ensured that cooperation with China in space has never got off the ground, meaning China could not be included in the ISS.

The total exclusion of China by the US, Bowen notes, has seen China develop its own capabilities, thanks to its own economic capacities, and Beijing may come to challenge the US to a symbolic leadership in human spaceflight and orbital space science.

"I would guess that the Trump administration’s response to this is that some private actor will do a follow up to the ISS. Privatising the ISS will not stop the inevitable – it will be too old to stay up at some point.

"Chinese prestige will be enhanced when the ISS is eventually deorbited and there is no replacement for it. This could be a serious move to a post-American future in space exploration and science. But only time will tell."

NASA astronaut Robert Curbeam works on the International Space Station's S1 truss during the space shuttle Discovery's STS-116 mission in December 2006.