Don Peterson (right) eats and confers with Commander Paul “P.J.” Weitz during STS-6. Weitz died last year. Photo Credit: NASA, via Joachim Becker/SpaceFacts.de

Veteran astronaut Don Peterson, who flew aboard STS-6, the maiden voyage of orbiter Challenger, performed the first-ever spacewalk from the shuttle airlock and might—had the hands of fate turned differently—have launched to the Air Force’s classified Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL), died Sunday (27 May). He was 84. Coming only days after the passing of Apollo Moonwalker and Skylab veteran Alan Bean, Peterson’s death deprives the world of yet another member of the “old guard” of pioneering U.S. astronauts. “So sad to report that we have lost another member of the astronaut family,” the Association of Space Explorers (ASE) noted Monday on its Facebook page. “Fair skies and tailwinds, Don.”

The STS-6 astronauts undertake slide wire basket training at Pad 39A during their Terminal Countdown Demonstration Test (TCDT). From left to right are Karol “Bo” Bobko, Paul Weitz (partially obscured), Story Musgrave (facing camera) and Don Peterson. Photo Credit: NASA, via Joachim Becker/SpaceFacts.de

Donald Herod Peterson was born in Winona, Miss., on 22 October 1933, and grew up loving adventure stories and science fiction. His next-door neighbor, Joe Glenn, a Second World War II fighter ace and veteran pilot of the Lockheed P-38 Lightning, offered Peterson his first glimpse of the aviation world. “He was kind of a town hero,” Peterson later recalled in his NASA oral history. “Since he lived next door, I could go visit with him and he used to talk about flying.” At high school, the young boy gravitated towards mathematics and physics and entered the Military Academy at West Point, N.Y., to study science. He earned his degree in 1955 and spent the next four years as an instructor pilot in the Air Training Command, performing formation and instrument flying and aerobatics. Years later, Peterson credited those years as pivotal in enabling him to enter test-pilot school.

He was detailed to follow a nuclear-powered aircraft program and a master’s degree in nuclear engineering at the Air Force Institute of Technology at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio. Unfortunately, six months before Peterson graduated, the program was canceled. He moved into technical intelligence, with a focus on nuclear reactor systems and served as a fighter pilot with Tactical Air Command, before entering the Aerospace Research Pilots School at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif. In June 1967, Peterson was selected as one of four pilots in the third group for the Air Force’s ill-fated MOL program, a military space station for orbital surveillance and reconnaissance. He participated in water and jungle survival training and later recalled that, such was the classification of MOL, he was required to travel around the United States on false identification papers.

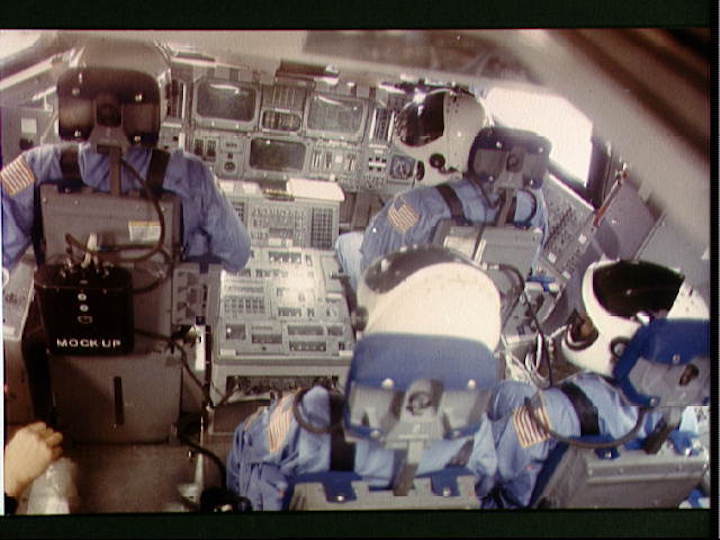

The STS-6 crew participate in a training session in the flight deck simulator. Peterson sits at the bottom-right side of the picture. Photo Credit: NASA

As MOL guzzled ever more money, and unmanned spy satellites became ever more capable, the space station program was canceled by President Richard Nixon in June 1969. Three months later, Peterson and six other ex-MOL pilots—including his future STS-6 crewmate Karol “Bo” Bobko—were hired by NASA into its astronaut corps. Part of the reason was that NASA needed Air Force support to gain Congressional approval for the shuttle program. “It won’t hurt,” NASA Associate Administrator for Manned Space Flight George Mueller told Deke Slayton, the head of Flight Crew Operations, “to make [the Air Force] happy, just this once!”

However, as Project Apollo wound down, there were few flight assignments for the new astronauts and Slayton selected only the candidates who were younger than 36 years old. By September 1969, Peterson was a few weeks shy of the deadline and, luckily, barely made the cut. He worked on the support for Apollo 16 in April 1972—the second-to-last manned lunar landing mission—before being reassigned to work on testing the avionics, computers, guidance equipment, navigation controls and air data systems for the shuttle. Working with fellow ex-MOL selectee Hank Hartsfield, Peterson helped devise techniques for a manually-controlled shuttle ascent. He retired from the Air Force as a colonel in 1979 and remained with NASA as a civilian astronaut.

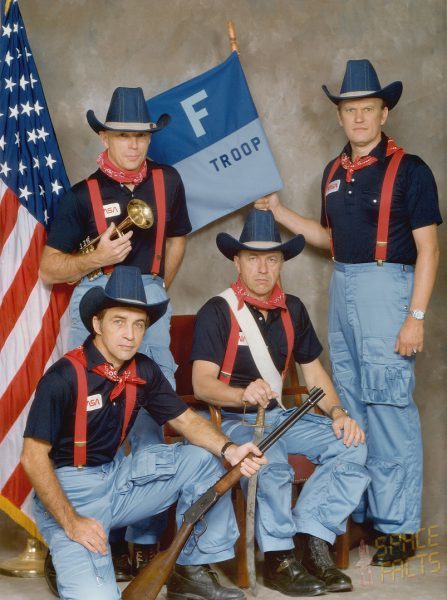

Weitz (seated) is flanked by Don Peterson (kneeling) and Musgrave (standing left) and Bobko (standing right) in the STS-6 crew’s F-Troop gag portrait. Photo Credit: NASA

In March 1982, Peterson was named as a Mission Specialist on STS-6, targeted to be the maiden flight of shuttle Challenger and scheduled for launch in January of the following year. Teamed with Commander Paul “P.J.” Weitz, Pilot Karol “Bo” Bobko and Mission Specialist Story Musgrave, the quartet dived into training for a two-day mission to deploy the first of NASA’s powerful Tracking and Data Relay Satellites (TDRS). However, STS-6 changed beyond recognition in November 1982, when the sickness and space suit problems left the crew of STS-5 unable to perform the first shuttle-based spacewalk. At short notice, Peterson and Musgrave were assigned to do a four-hour spacewalk on STS-6. To accommodate this complex new objective, their mission was extended to five days.

“It didn’t give us much time to train,” recalled Peterson. “I didn’t have much experience in the suit, but the advantage we had was that Story was the astronaut office’s point of contact for the suit development, so he knew everything there was to know. He’d spent 400 hours in the water tank, so he didn’t really have to be trained.”

Challenger roars into orbit on her maiden voyage. Photo Credit: NASA

After several delays, Challenger rocketed into orbit on 4 April 1983. The astronauts informally labeled themselves “The F Troop”, in recognition of the fact that they were the sixth shuttle crew, and Weitz arranged for gag photographs of them with Civil War attire—cavalry hats, braces and red-and-white neckties—together with lever-action rifles, bugles, swords and cavalry flags. Although NASA did not appreciate the humor, the crew found it hilarious. However, with an average age of 48, the astronauts on STS-6 were one of the oldest crews ever launched…and their younger colleagues decided to nickname them “The Geritol Bunch”, after the dietary supplement famously associated with aging.

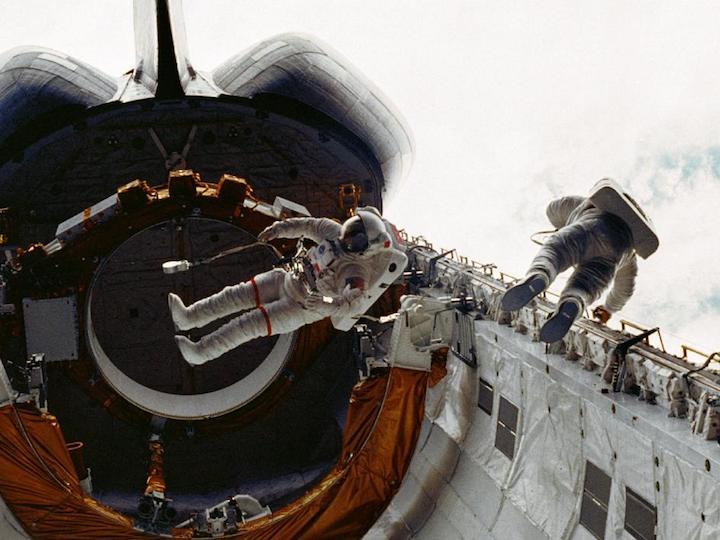

By his own admission, Peterson’s spacewalk training had been rushed and he was underwater for only 15-20 occasions, “and that’s not really enough to know everything you need to know”. Yet his four hours outside Challenger with Musgrave ran very smoothly. The two men practiced moving themselves along slide wires fixed to the payload bay sills and evaluated a hand-cranked winch to manually close the payload bay doors in an emergency. At one point, during a high metabolic period, whilst working with a ratchet wrench, Peterson received a high oxygen usage alarm on his suit. It was later attributed to a flexion-induced leak in the suit, coupled with his high work rate. The alarm quickly cleared and did not recur. As luck would have it, the alarm occurred whilst Challenger was out of direct communication with the ground, so the astronauts continued their tasks. “They weren’t watching at the time that happened,” Peterson said later. “By the time we dumped the data from the computers to the ground that showed the leak, we were back inside the orbiter.”

Story Musgrave (left) and Don Peterson perform the Shuttle program’s first EVA. The large tilt-table, used earlier in the mission to deploy the first Tracking and Data Relay Satellite, is visible in the background. Photo Credit: NASA

Almost certainly, had Mission Control spotted the alarm in real time, Musgrave and Peterson would have been immediately directed back to the airlock.

The view was truly spectacular. “The shuttle flies with the payload bay towards Earth all the time, but we thought it would be neat when we got on the dark side if we could look out at the night sky and see all the stars,” remembered Peterson. “We did better than that. When we were on the daylight side, we went into the Ferris-wheel mode. Just like a Ferris-wheel seat goes around and never changes attitude, we went around the world, holding one attitude, so when we got on the dark side we faced exactly away. We got some beautiful pictures of Earth from different attitudes that we couldn’t have done otherwise.”

Peterson retired from NASA in November 1984 to enter aerospace consultancy. At the end of his career, he had logged in excess of 5,300 hours of flying time, including more than 5,000 hours in jet aircraft. With STS-6, he also logged five days in space and four hours of spacewalking time. His passing comes only a few months after the death of his STS-6 crewmate Paul “P.J.” Weitz and AmericaSpace extends its sincere condolences to his family at this time.

Quelle: AS