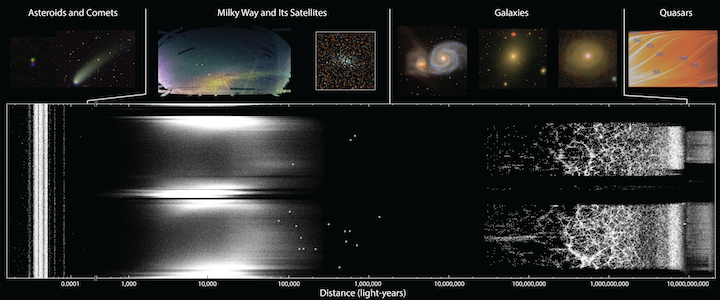

A map showing some of what the Sloan Digital Sky Survey has discovered over the last twenty years.

The dots show the distance to various sky objects that the SDSS has discovered. The horizontal axis of the map is labeled in light-years, stretching from our own solar system to the most distant reaches of the universe. Sample images at the top show some of the things the SDSS has seen.

Image Credit: V. Belokurov, M. R. Blanton, A. Bonaca, X. Fan, M. C. Geha, R. H. Lupton, the SDSS Collaboration

The observers’ log said: “Wow, what a night!”

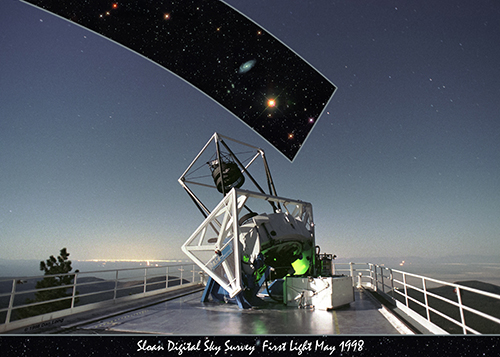

This week marks the twentieth anniversary of “first light” for the telescope behind the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS), which has gone on to create by far the largest three-dimensional map of the Universe ever made. Early in the morning of May 10th, 1998, the observers and engineers pointed the Sloan Foundation Telescope to the celestial equator and light went through to the survey’s exquisitely sensitive camera. When dawn broke after a long night’s work, SDSS observer Dan Long emailed his usual observer’s log summarizing what happened. After describing the technical details of the observations, and before noting a series of newly identified problems to fix, he wrote: “Wow; What a night!”

“That was the beginning of our survey, and we’re still going strong twenty years later,” says Michael Blanton, a professor at New York University and the Director of SDSS-IV. “We are now planning our fifth generation, called SDSS-V, and we’re still using the same Sloan Foundation Telescope.”

Michael Blanton

“That was the beginning of our survey, and we’re still going strong twenty years later.”

The telescope’s mirror, 2.5 meters (8 feet) in diameter, is small by astronomy research telescope standards, but powerful because it can see a large area of the sky simultaneously. Astronomers have used it to make an enormous, highly-detailed map – a map which covers one-third of the night sky, with measurements of hundreds of thousands of Milky Way stars and distances to more than four million galaxies. All the data collected by the telescope is available free to anyone online, and all images are open access under the SDSS’s Image Use Policy.

This map has played a key role in astronomical history, helping astronomers learn about our Milky Way, other galaxies, distant black holes, the nature of dark matter and dark energy and myriad types of stars in ways never imagined when the project started.

The SDSS has measured the universe’s expansion more precisely than ever before and has mapped how galaxies and larger structures grew over cosmic time, helping to establish our current standard model of cosmology. It discovered some of the nearest stars and the smallest companion galaxies to our own Milky Way galaxy, revealing how our galaxy grew by cannibalizing smaller galaxies. It has studied the Milky Way’s disk of stars more completely than ever before, using infrared light to peer through the obscuring dust. It has studied the dark matter content of the Milky Way and distant galaxies, and found some of the most distant quasars known.

And perhaps most importantly, the SDSS has achieved its remarkable scientific discoveries while establishing a new way of doing science. Since 2001, the project has made all its data freely available to the public in a series of roughly-annual releases of data – most recently with Data Release 14 in July 2017. The team who built and operated the survey recognized that the data were far too rich for them to reap all the science from it alone, and that maximizing the science return would require the entire worldwide community of astronomers. As a result, a generation of astronomers have grown up learning their craft with the help of SDSS data. Close to ten thousand astronomers have worked with SDSS data, publishing over eight thousand scientific papers – thus making it the most broadly used data set in astronomy.

Along the way, SDSS gained the support of numerous institutions. One-quarter of the funding for SDSS comes from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, and about five percent comes from the U.S. Department of Energy. The rest comes from more than fifty universities and research institutions on four continents, all of whom consider it so vital to their scientists that they contribute their time, effort, and resources to become members of the project. The next step, SDSS-V, will commence in 2020 and will continue to uncover the unexpected by observing millions of stars, galaxies and black holes across the entire sky.

At the Apache Point Observatory, home of the Sloan Foundation Telescope, astronomers will gather this Wednesday, 9th May 2018, to mark this anniversary, remember the early days of the project, and discuss the impact it has had on the field of astronomy. The telescope no longer hosts a camera, but it still measures spectra of hundreds of celestial objects every night – and is still operated by a dedicated on-site team of observers and engineers. True to the online nature of the Sloan Digital Sky Surveys over the last 20 years, this celebration will be broadcast live on the internet, and involve collaboration members past and present across all parts of the globe.

The core of the project – the people who get the data upon which so many of the world’s astronomers depend – sits the team of observers and engineers at Apache Point Observatory. A handful of the original team that led the efforts in 1998 are still with the project. Dan Long was promoted along the way to Chief Telescope Engineer, a position from which he recently retired. Many other members of the team have joined more recently. But they all share the excitement that Dan Long expressed the night of first light, and each night brings the prospect of new discoveries that will change the way we see our universe and make them and us say “Wow.”

Quelle: Astrophysical Research Consortium (ARC) and The Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS)